Kazakhstan’s energy grid has not been modernised since its independence from the Soviet Union and is falling into a state of dereliction and disrepair. With its sights set on 50 percent renewable energy by 2050 and substantial solar and wind energy capabilities, Kazakhstan could be a model for green energy development. Funding from the BRI offers a unique opportunity to rebuild Kazakhstan’s energy grid using renewable energy.

Background

Kazakhstan’s current energy grid was developed during the Soviet Union and is heavily reliant on its interior coal, gas, and oil resources. Following independence, economic crises prevented the country from investing in the maintenance and development of the grid. Today, this dereliction manifests as low efficiency with the average 1000MW coal plant having only a 27% net efficiency.1 At the same time, the funding available domestically for improving the grid has been limited further by national electricity subsidies. These subsidies are protected by the threat of provoking political unrest, a common response to electricity pricing increases across Asia.2 Since ratifying the Kyoto protocol, Kazakhstan has also set ambitious goals for shifting the country’s electric power generation to renewable resources. Kazakhstan intends for renewable energy to constitute 30 percent of electricity generation by 2030 and 50 percent by 2050. Below I will make the case that there is significant opportunity for BRI investment to build up solar and wind energy. The most effective means of implementing these goals would be for future solar projects to focus on implementing parabolic trough high-temperature solar thermal collectors (in which curved, reflective ‘troughs’ concentrate radiation from the sun on a pipe containing a heat transfer fluid, which then creates high-pressure superheated steam which can generate electricity) in Kazakhstan’s energy-deficient southern region and wind projects to focus on developing wind farms in Djungar in the east. These recommendations ensure the most effective use of funding with regard to energy output and energy infrastructure development, while keeping in mind Chinese regional interests.

The Case Against Hydropower

Among renewable energy resources, hydropower is frequently raised as a source of energy for Central Asian countries. However the region’s over-reliance on this technology has become self-defeating and alternative sources are needed. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers have become geopolitical flashpoints in the region as the five Central Asian countries have attempted to maximise the rivers’ hydroelectric and irrigation potential. A lack of environmental planning and international coordination in these efforts has not only created political setbacks, but it has decimated the Aral Sea, into which the two aforementioned rivers flow. While Kazakhstan does have limited hydroelectric capabilities, these factors point to the conclusion that large-scale development of Kazakhstan’s power grid would be best implemented in other renewable energy sectors. As a solution to these limitations, this proposal advocates for future BRI investment to be directed toward developing Kazakhstan’s solar and wind energy infrastructure capabilities, these factors point to the conclusion that large-scale development of Kazakhstan’s power grid would be best implemented in other renewable energy sectors. As a solution to these limitations, this proposal advocates for future BRI investment to be directed toward developing Kazakhstan’s solar and wind energy infrastructure.

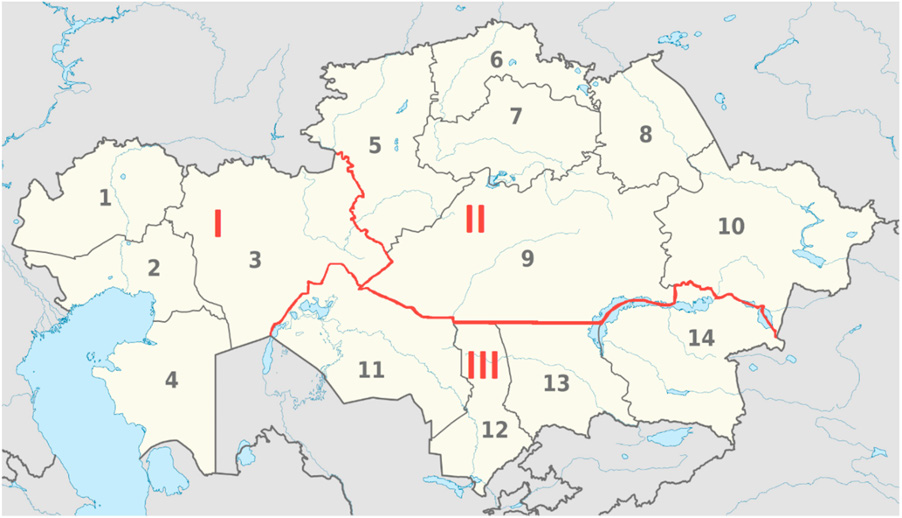

Note: I (Western Zone): 1 – West Kazakhstan Region; 2 – Atyrau Region; 3 – Aktobe Region; 4 – Mangystau Region; II (Northern Zone): 5 – Kostanay Region; 6 – North Kazakhstan Region; 7 – Akmola Region; 8 – Pavlodar Region; 9 – Karagandy Region; 10 – East Kazakhstan Region; III (Southern Zone): 11 – Kyzylorda Region; 12 – South Kazakhstan Region; 13 – Zhambyl Region; 14 – Almaty Region.

Source (map and legend): Jianzhong Xu, Albina Assenova, and Vasilii Erokhin, “Renewable Energy and Sustainable Development in a Resource- Abundant Country: Challenges of Wind Power Generation in Kazakhstan,” Sustainability 10, no. 9 (September 17, 2018): pp. 1-21, https://doi. org/10.3390/su10093315, p.6.

“Since ratifying the Kyoto protocol, Kazakhstan has also set ambitious goals for shifting the country’s electric power generation to renewable resources.”

Solar Power

As for solar energy, the southern part of the country, including the Kyzylorda and South Kazakhstan Regions, proves to have the highest levels of insolation. Developing solar energy in this area could be especially beneficial, as its energy demands currently exceed that which it is able to supply locally, meaning it is often necessary for the region to source energy from the north of the country. Concentrated solar thermal collectors are the most advantageous for this region as, in comparison to solar photovoltaic panels, they are more efficient, their materials can be sourced locally within Kazakhstan, and their basic functioning does not rely on the use of water to the extent that solar photovoltaic panels do.3

In 2016, construction began in the Akmola Region on a 100MW solar power plant, funded by KB Enterprises and Siemens. Similar plans have been announced by KB Enterprises and Siemens to build additional plants in Almaty, South Kazakhstan, Kyzylorda, and Karaganda. The Hevel group also financed a project in the Akmola Region in 2019 for a 100MW photovoltaic solar farm. Additionally, in 2019 the Asian Development Bank agreed to provide funding for another 100MW solar farm in the southeastern Jambyl Region. The Eni Group, in line with the aforementioned guidance, announced it will provide funding for a 50MW photovoltaic plant in the southern region of Turkestan earlier this month.

Wind Power

According to Karatayev and Clarke, Kazakhstan has a maximum capacity of 760 GW of wind energy that can be generated cost-effectively in the Atyrau Region and in a belt to the west of Nur- Sultan stretching across the Kostanay, Akmola, and Karagandy Regions4. In the former region, wind power is the strongest, especially in Fort Shevchenko, and may be competitively priced in comparison to gas-fired energy dominant in the region. In the latter, while the strength of the wind is weaker, the power generated may still be produced at a lower cost than the region’s established coal-burning industry.5 However, it is also worth noting that there are opportunities for wind energy development outside of these two areas as well. Xu et al. note that one of the most promising areas for wind energy development is Djungar, along the border with Xinjiang.6 Not only does this area boast strong and frequent wind, but the implementation of wind energy technology in this region is predicted to generate the greatest reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in all of Kazakhstan7.

There are already some projects for developing Kazakhstan’s wind energy infrastructure. The Zheruyik Wind Power Plant, financed by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD, is expected to generate 50MW of wind power in the Almaty region with the objective of providing energy for southern Kazakhstan where it would otherwise have to be sourced from fossil fuel plants in the northern part of the country. The Zhanatas Wind Power Plant, financed by the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, the Green Climate Fund, and the EBRD, is also planned for the southern region of Zhambul hopes to generate another 100MW to help alleviate this issue. In contrast, the Eni Group and General Electric have provided funding for the construction of the Badamsha 1 48MW capacity wind farm in the Aktobe Region. The EBRD and Clean Technology Fund Trust Fund Committee have also provided funding for the Yereymentau 50MW Wind Farm in the northern Akmola region. As for western Kazakhstan, South Wind Power LLP and Horgos Jiuhe SilkBridge New Energy Co are financing a 42MW wind farm in Mangistau near the critical area of Fort Shevchenko. Progress in the development of wind energy in Kazakhstan has been encouraging but should not be limited to the above projects. Future BRI investment in Kazakh wind energy may be best directed toward the region of Djungar, which has not only been shown to be an especially viable area for wind energy development, but may interest Chinese firms particularly due to its proximity to the border with Xinjiang.

Lessons Learned from Iran

Like Kazakhstan, Iran has similarly struggled with the transition from dependence on its own fossil fuel reserves to renewable energy. Where Iran has started this transition, efforts to convert existing energy infrastructure to renewables have largely been consumed by a focus on hydropower. However, in Iran, the development of hydropower has been hampered by extensive droughts. This has made the development of wind and solar energy all the more attractive.

While Iran has the greatest capacity for wind energy, it hopes to invest more into its solar energy development in the long term. Research into Iran’s solar capacity has illuminated important issues for Kazakhstan to consider as it continues to develop its own solar industry. Importantly, Kalehsar notes that air pollution has the capability to interfere with solar panel performance. It seems as though the bulk of Iran’s solar energy is generated through photovoltaic panels which negatively impact the country’s ability to apply this technology. Because photovoltaic panels’ functioning is diminished under high temperatures, this leaves only five northern provinces fit for solar energy production in Iran. In contrast, the energy generating technology within parabolic trough high-temperature solar thermal collectors functions at temperatures between 260 degrees Celsius and 400 degrees Celsius. Collectors of this type are used in plants such as the Solana Generating Station in Gila Bend, Arizona, USA where temperatures reach highs of over 42 celsius, which is above the average summer high temperatures in one of Kazakhstan’s southernmost cities: Shymkent.

“Research into Iran’s solar capacity has illuminated important issues for Kazakhstan to consider as it continues to develop its own solar industry.”

Looking Forward

Overall, the development of Kazakhstan’s renewable energy grid is encouraging, but could benefit greatly from further BRI funding. Only three of the aforementioned solar and wind energy projects have benefitted from Chinese funding: the Jambyl solar plant, the Zhanatas wind farm, and the Mangistau wind farm.

The recommendations for future BRI funding in this sector are as follows:

- Recognising Kazahstan’s central role in the BRI, Chinese firms should aim to be more competitive with their European counterparts in funding development of Kazakh solar and wind energy infrastructure.

- Development of solar energy infrastructure should be focussed in the south with the goal of making the region self-sufficient. Future projects should implement parabolic trough high-temperature solar thermal collectors, which are better suited to local conditions and their constituent materials can be sourced within Kazakhstan.

- The next stage of wind power infrastructure development should focus on Djungar, one of the most promising regions for wind energy generation in Kazakhstan and a location which holds significance for Chinese regional interests.

[1] Sarbassov et al., “Electricity and Heating System in Kazakhstan: Exploring Energy Efficiency Improvement Paths,” p.433.

[2] MacGregor, “Determining an Optimal Strategy for Energy Investment in Kazakhstan,” pp.211-212.

[3] Karatayev and Clarke, “A Review of Current Energy Systems and Green Energy Potential in Kazakhstan,” p.498.

[4] Karatayev and Clarke, “A Review of Current Energy Systems and Green Energy Potential in Kazakhstan,” pp.498-499.

[5] Xu, Assenova, and Erokhin, “Renewable Energy and Sustainable Development in a Resource-Abundant Country: Challenges of Wind Power Generation in Kazakhstan,” pp.10-11.

[6] ibid., pp.12-13.

[7] ibid.

Disclaimer

The report is published by the Oxford University Silk Road Society Think Tank with the support of the IIGF Green Belt and Road Initiative Center. ‘The Central Asia Way’ policy report analyses the social and environmental impacts, risks, and opportunities for regional partners and China as BRI projects continue to expand into Central Asia. This report maps out the intersection of BRI with Central Asia’s development path, and argues that an opportunity is open to explore innovative responses to the challenges of green governance.

The Oxford University Silk Road Society was established in 2017 by enterprising students keen to explore, research and discuss the countries, cultures, and peoples of the Silk Roads, both modern and historical. Through case studies or holistic reports, the think tank strive to produce rigorous, detailed analysis on the ongoing efforts to improve sustainability in the China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and make their own policy recommendations – to governments and private enterprise alike.

The full report is available on the Oxford University Silk Road Society’s website here or on our website here, with a foreword from the Founding Director of the Green BRI Center, Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG.

Julia Irvin is reading for a MPhil in Modern Chinese Studies at the University of Oxford. Previously, she completed a Master of Arts (Honours) in Arabic, Russian, and International Relations at the University of St Andrews. Her research interests include political violence and identity studies and she is planning to focus her doctoral research on Central Asia.

Comments are closed.