On May 20, 2019, the Ministry of Transport and 12 other ministries jointly issued the Green Travel Action Plan (2019-2022), which will further promote the large-scale application of green vehicles and accelerate the construction of charging infrastructure. China will also continue to improve public transportation facilities, connectivity and information systems that are supporting green mobility.

China has been a role model in providing public transport services for its population for many years. Compared with countries of a similar development state, and even compared to most countries with a higher GDP per capita, China has a higher density of modern public transportation services for both urban public transportation services and inter-city public transportation services.

Most notably are three developments in China that contributed to that achievement:

- Development and construction of High-speed trains

- Development and construction of subway systems

- Development and deployment of electric buses

This article will look at China’s green public transportation development and how BRI countries can profit from Chinese experiences.

Green public transportation development in China

China’s public transportation system has for many decades been dependent on buses and rail. Over the last 15 years, with strong public support through policy, investment and technological developments, China’s public transportation system has improved dramatically to a level that is more advanced than most developed countries. This has allowed Chinese citizens not only to travel more seamlessly both within and between cities, but has also enabled China to significantly decrease emissions per passenger kilometer travelled.

In addition, the investment, construction and operation of these services has allowed China to become and a leader in green transportation innovation, as well as the leading producer and operational expert in green public transportation.

Development of Chinese high-speed rail (HSR) network

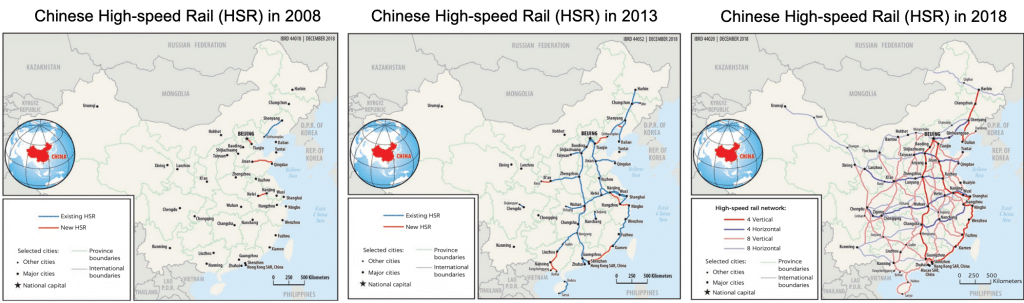

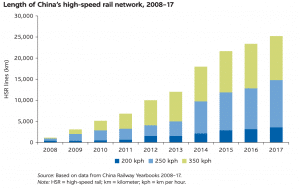

The Chinese high speed trains are called 高铁 (Gao Tie). In 2007, China only operated one high-speed rail (HSR) line (with speeds above 200 km/h), the 404km long Qinghuangdao-Shenyang passenger railway. Within 4 years, by 2011, China became the country with the longest high-speed network in the world with about 8,500 km of tracks.

By the end of 2019, China will have 30,000 km of high-speed railway network in operation, connecting about 200 Chinese cities.

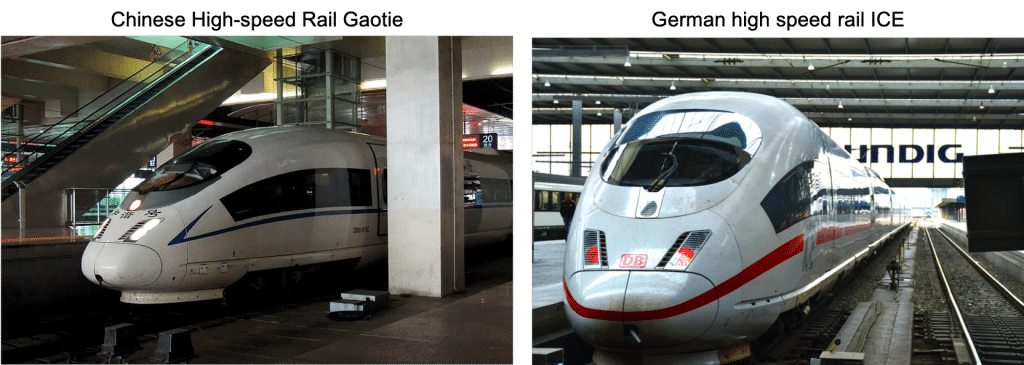

While some of the original high-speed train technology was transferred from German Siemens, French Alstom, or Japanese Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Chinese engineers have re-designed and built fully Chinese made trains manufactured by the state-owned CRRC Corporation. This has enabled Chinese HSR to achieve records, such as world’s fastest operating conventional train service (Beijing to Shanghai) and world’s longest high-speed rail line in operation from Beijing to Guangzhou.

The funding to construct and operate high-speed rail (construction cost of high-speed rails range between 30 million RMB per kilometer (the Jiaoji PDL from Qingdao to Jinan) and 204 million RMB per kilometer (the Chengguan PDL from Chengdu to Guanxian)) come mostly from public sources, such as policy banks. In addition to public funding for construction, private funding methods are also being developed. In April 2019 privately held Fosun, together with a broader consortium, signed a deal to build the first privately held high-speed rail covering 267 km from Hangzhou to Taizhou – all in East China’s Zhejiang Province.[1]

China has done particularly well in expanding its high-speed rail due to high technical capacities, quick learning from international experiences, strong policy support regarding construction permits, and public investments.

Development of Chinese subways

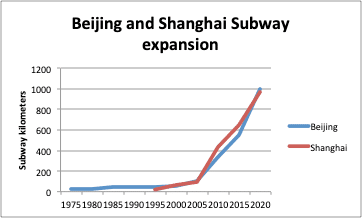

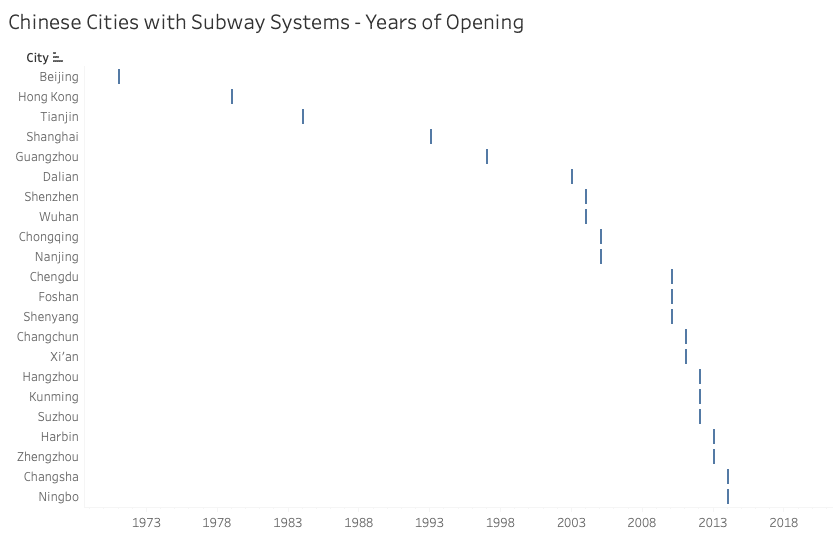

China built its first subway line in Beijing in 1969, its second in Hong Kong in 1979 and its third in Tianjin in 1984. Shanghai got its first subway line in 1993. But it was not until the early 2000s, when Chinese people could really enjoy wide accessibility of subways. Starting in the early 2000’s, Chinese cities started to expand subway coverage in terms of cities with subways and in terms of subway stations within the city. For example, Beijing only operated 53 km of subway lines and Shanghai 65 km in the year 2000. Today in 2019, they are the world’s two largest subway systems in 2019 with 628 km in Beijing and 676 km in Shanghai.

Of the 35 Chinese cities with subway systems today, 25 started operating after the year 2010 and 6 additional Chinese cities are currently constructing a new subway.

Chinese subways moved about 23 billion people in 2018 – about 4 times as many people as the world’s second business subway system – Japan’s.

Chinese subway systems are also leading the way in terms of cashless payment technology. Not only can riders use QR codes and NFC technology to pay their fees, face-recognition is also used to pay for fees, for example in Shenzhen. This is in contrast to New York’s subway, which didn’t introduce its first cashless payment system until June 2019.

While subways provide a convenient and green option for mass-mobility, multiple studies show that surrounding areas of subway stations have also profited in terms of increased residential property values[2]. This illustrates that returns on subway investments should take into account more than the fares that often don’t suffice to cover the cost of capital.

Chinese experience is particularly pronounced in terms of construction speed, daily operations and application of new technologies. China’s subway boom has also been made possible by strong public investments and an integration of broader policy goals and benefits (e.g. the increase in real-estate prices).

Development of Chinese electric urban buses

In 2017, Shenzhen became the first city in the world to exclusively use electric buses for its public transportation. Each of the 16.000 electric buses in operation saves “356 tonnes of carbon dioxide, 28kg of nitrogen oxide and 26kg of particulate matter” per year, according to the Shanghai Municipal Transportation Commission. This calculation includes the pollution from electricity generation based on the current energy production mix of the city.[3] Chinese electric buses have displaced around 2% of oil consumption since 2011, according to Bloomberg.[4]

Overall, there were about 425.000 electric buses in the world at the end of 2018, 421.000 of which in China[5], 99% of the world’s stock. In Europe, in contrast, the biggest electric bus fleet in 2018 was in Amsterdam with around 100 electric buses.[6]

While global electric bus markets are expected to grow rapidly, the two biggest producers of electric buses are Chinese: BYD from Shenzhen and Yutong from Zhengzhou. BYD in February 2019 celebrated producing its 50,000th electric bus.[7]

The success of Chinese electric bus system is due to strong policy support in terms of subsidies, but also due to political ambitions and local engineering capacities, for example, of battery technology.

Chinese experiences in electric buses are particularly strong and relevant for BRI countries in terms of hardware (buses), planning (e.g. charging infrastructure), and operation (e.g. when does a bus need to charge, for how long).

Chinese Green Mobility for BRI countries

China has gained the necessary expertise in all dimensions – construction, financing and operation – to install and manage vast networks of public transportation. This expertise should be used more to support BRI countries in their green mobility transition.

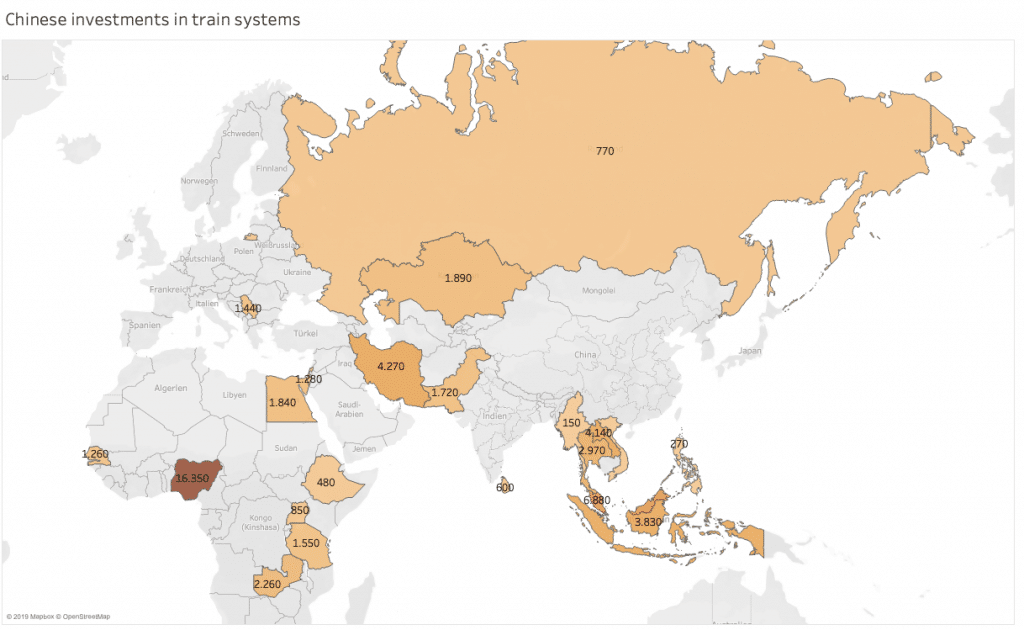

Over the past years, China has become one of the most important investors in much needed infrastructure in emerging economies through its Belt and Road Initiative. It has already supported several countries in building inter-city train systems, subways and exported e-buses. Over the last 5 years alone, China has invested almost 75 billion USD in train systems worldwide, with the biggest recipients being Nigeria, Malaysia and Indonesia.[8]

Specific projects include

- a high-speed rail in Europe – that connects Hungary’s capital Budapest to Serbia’s capital Belgrade with an investment of about 2,5 billion USD

- the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed rail in Indonesia, which is partly financed by the Chinese Development Bank

- A 4.6 km subway extension in Moscow, Russia built by China’s CRCC is building

- A 19.7 km subway construction in Hanoi, Vietnam by China Railway Sixth Group

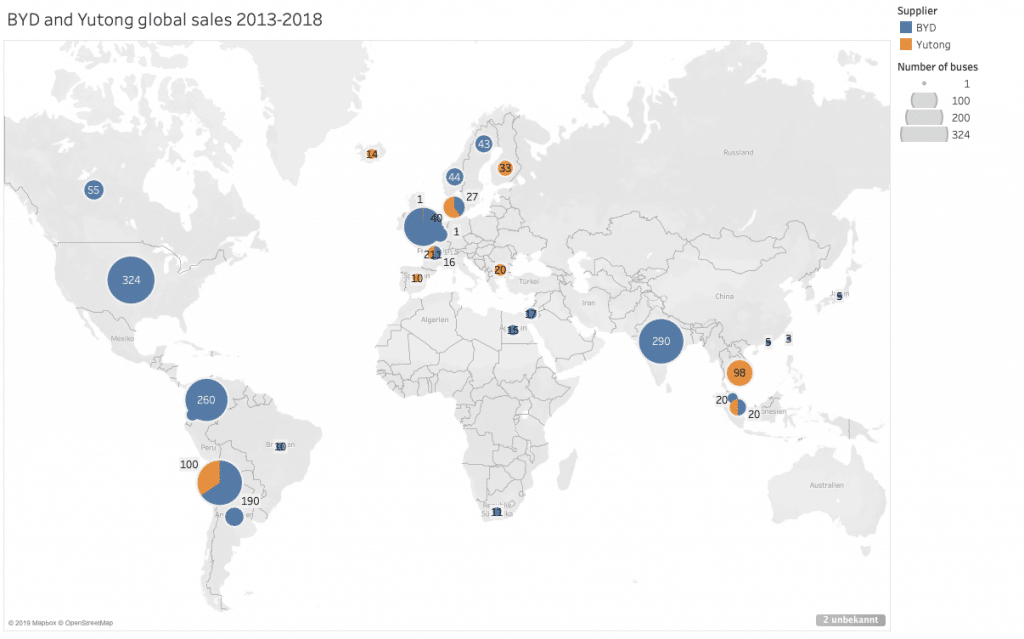

- Application of BYD and Yutong electric buses in more than 30 countries, with the biggest markets so far in the USA (with 324 BYD buses) and India (with 290 BYD buses).

Looking at the massive need for green mobility in BRI countries, however, the utilization of green mobility solutions from China, particularly high-speed rail, subways and e-buses is still very small. Overall, just over 2,000 electric buses have been exported by BYD and Yutong (see Figure 2), international high-speed rail construction is still in its infancy and subways are built in less than a handful of BRI countries.

The main reason for the lack of the investments in innovative and green public transport systems is the high cost of construction, acquisition of hardware and operation/maintenance of the transport systems – as well as lack of policy/planning capacity. This is an important responsibility and opportunity for China with its expertise in fast and affordable construction, policy making and investment to share its experiences and support BRI countries in applying green public transportation innovation.

Recommendations

China has successfully embarked on a green mobility transition. It has created an innovation ecosystem with experienced investors, construction companies and innovative companies providing both globally leading and innovative hardware (e.g. high-speed trains, subways and e-busses) and operations. With the green Travel Action Plan issued in May 2019, Chinese green transportation system will further gain importance within China and worldwide.

Belt and Road Initiative countries should take the opportunity to work with China to build their own green mobility system. In order to accelerate this, Chinese and BRI stakeholders should emphasize the following:

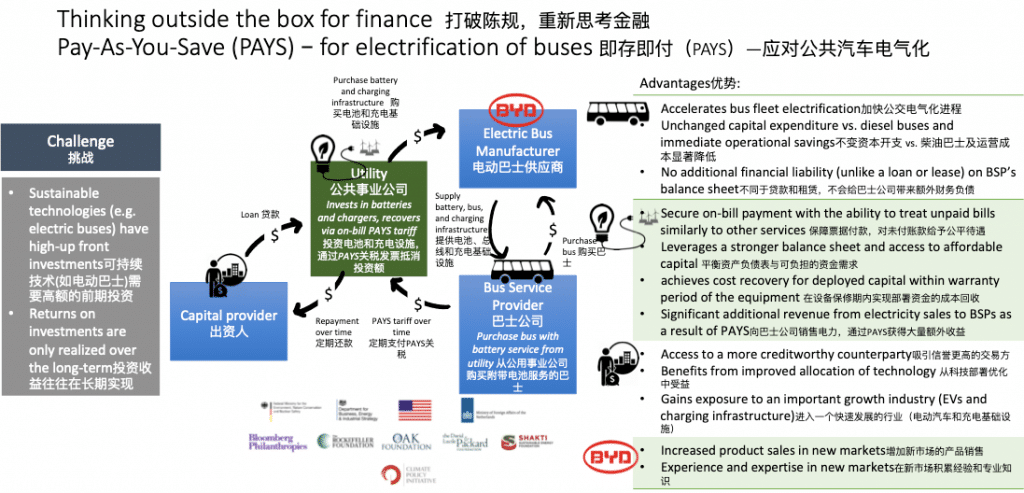

- allow for new forms of blended and mixed financing that allows cash-strapped operators of transportation system to finance the equipment, such as more expensive electric buses. In practice, this could mean that the operator of the buses only pays for the regular price of the bus, while the electricity provider pays for the additional cost of an electric bus. The electricity provider earns extra money from the necessary electricity of the e-bus, while the bus operator saves cost on fuel. This model, also referred to as PAYS, has been tested, for example in South Africa.

- set up joint-funds for broader urban development that includes urban real estate: Chinese and local investors (e.g. under the leadership of China Development Bank or China Exim Bank) should set up a common fund that develops both green transport (e.g. subways) and real estate to profit from the increase in value of real estate. Local governments should set the necessary policies to a) force these funds to also invest in public transport and b) allow them to profit from the increase in real estate value.

- Create local capacity building and innovation programs that allows local stakeholders to profit from the influx of investments and new technology. While there should be no forced technology transfer from Chinese innovation to local stakeholders, local business could profit by providing important ancillary services (e.g. construction, electric charging infrastructure, maintenance, operations). This in turn will help the local economies to further accelerate.

- Local government should set better incentives for green finance investments that allow investment in green mobility, for example through tax breaks, subsidies or special green bond incentives. This is particularly important for public transportation that needs to be accessible for all income groups, meaning prices need to be affordable.

- Increased efficiency planning for green mobility technology: Chinese providers of big data analyses should help plan green transport systems that takes into account local stakeholders needs and habits and allows for local policy goals (e.g. zoning of urban areas) to be implemented.

[1] “China’s First Private High-Speed Rail Project Gets $4 Billion…,” Reuters, April 27, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-railway-idUSKCN1S304G.

[2] E.g. Dongfang Zhang and Jingjuan Jiao, “How Does Urban Rail Transit Influence Residential Property Values? Evidence from An Emerging Chinese Megacity,” Sustainability 11, no. 2 (January 20, 2019): 534, https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020534.

[3] Zigor Aldama, “Taking Charge: China Leaves World behind in Electric Bus Race,” South China Morning Post, January 18, 2019, https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/2182466/powered-state-china-takes-charge-electric-buses.

[4] Dan Murtaugh, “How Much Oil Is Displaced by Electric Vehicles? Not Much, So Far,” March 19, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-03-19/how-much-oil-is-displaced-by-electric-vehicles-not-much-so-far.

[5] Brian Eckhouse, “The U.S. Has a Fleet of 300 Electric Buses. China Has 421,000,” May 15, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-15/in-shift-to-electric-bus-it-s-china-ahead-of-u-s-421-000-to-300.

[6] Editorial, “Electric Bus, Main Fleets and Projects around the World,” Sustainable Bus (blog), October 2, 2018, https://www.sustainable-bus.com/electric-bus/electric-bus-public-transport-main-fleets-projects-around-world/.

[7] Mark Kane, “BYD Produced 50,000 Electric Buses In Nine Years,” insideEvs.com, February 11, 2019, https://insideevs.com/news/342760/byd-produced-50000-electric-buses-in-nine-years/.

[8] Scissors Derek, “China Global Investment Tracker 2018,” China Global Investment Tracker (Washington: American Enterprise Institute, January 2019), http://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.

[9] Derek.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.