Green finance in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that deals with climate change by mitigation or adaptation has received much attention over the past months. A topic that is gaining momentum for a “green Belt and Road Initiative” is green finance for biodiversity – or biofin. Three reasons drive this development:

- China will host the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP 15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) next year (tentatively from October 5 to 10, 2020 in Kunming), hoping to agree on a post-2020 framework for biodiversity conservation

- Biodiversity losses continue to accelerate with currently 1 million of 8 million known species under immediate threat

- Chinese Investments in the Belt and Road Initiative have a major impact on biodiversity loss and biodiversity protection

Although biodiversity protection has a long history (the first CDB COP took place at the end of 1994 in the Bahamas), progress on biodiversity protection has been insufficient. Among the many different instruments that will have to be developed and strengthened to support biodiversity protection, biodiversity finance (biofin) can play a major role.

Biodiversity risks in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

Within the countries of the Belt and Road Initiative, trillions of dollars are invested to build linear infrastructure such as roads, rails and electric power transmission, as well as other infrastructure such as mines or power plants. The goal is to increase connectivity between economies to increase trade and improve livelihoods, inspired by the Chinese experience of economic development in the past 40 years and based on infrastructure gap analyses by a multitude of multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, UN, AIIB.

Yet, infrastructure developments must be considered as intrusions into natural ecosystems. Infrastructure construction directly leads to breaks in landscape and habitat connectivity, but also to side-effects such as spread of invasive animal and plant alien species, windthrows, fires, animal kill (e.g. through roadkill), pollution, microclimates.

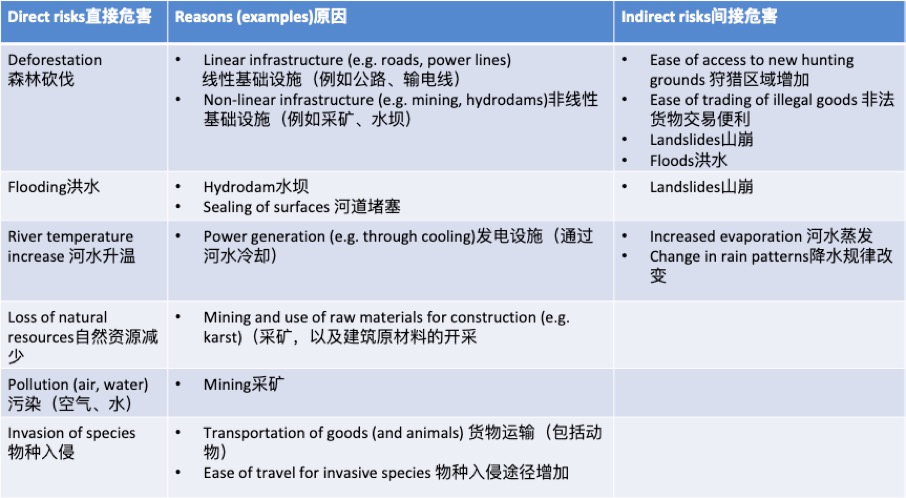

Particular risks that arise from infrastructure developments with an impact on biodiversity include:

- deforestation through the construction of roads, power lines etc., which also risks to easier access to new hunting grounds and easier trading of illegal goods, in addition to risks of landslides and flooding

- flooding through the construction of hydrodams or the sealing of surfaces through concrete on roads, which increases the risks of e.g. landslides

- an increase in water temperature, e.g. through the cooling of power plants, which also creates new micro-climates

- a loss of natural resources, e.g. through mining and use of raw materials such as karst

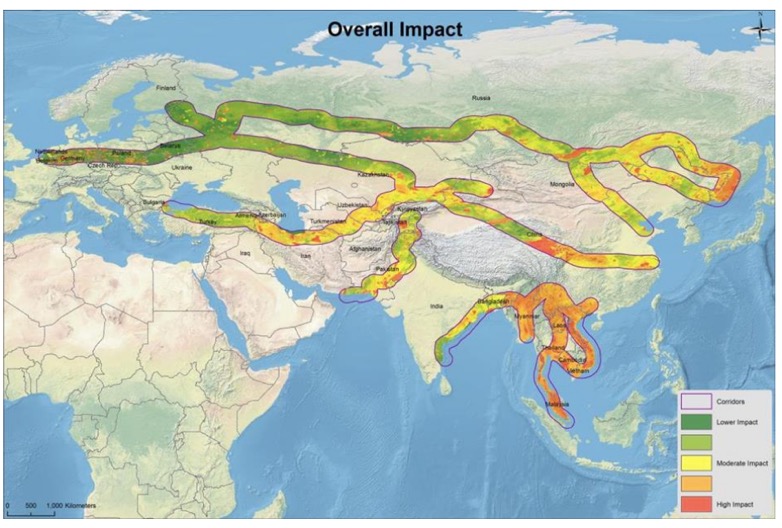

As a consequence from infrastructure development along the BRI, a study published in 2019, found that construction would endanger 4,138 animal and 7,371 plant species along the BRI and that, corridors of the BRI overlap with 265 threatened species, including endangered saiga antilopes, tigers and giant pandas, 1,739 important bird areas (IBA) or key biodiversity areas (KBA) and 46 biodiversity hotspots.

Awareness of the issue of biodiversity loss along the BRI is gaining increasing attention. Two cases stick out:

- In Niger, three oil blocs were awarded to the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). The oil blocs are located within the Termit & Tin Toumma Nature Reserve, that is considered one of the last pristine Saharan wildlife resorts, including the only habitat of the white antelope. In order to service the oil blocs, the Niger government said that the national park borders would be re-drawn. However, as many observers have noted: the new borders don’t provide the right habitat for many of the relevant species

- In Indonesia, a stretch of the pristine Batang Turo Forest is becoming the flood-area for a new 510 MW hydrodam built by Sinohydro. The Forest is home to a number of unique animals, including a new orangutan species that was only discovered in 2017 and the Sumatran tiger. The hydrodam would not only directly flood 10% of the habitat, but have to build service roads and power transmission infrastructure that cuts through the animals’ habitat.

Biodiversity Finance (Biofin)

Chinese President Xi has called to build a “green, healthy, intelligent and peaceful” Belt and Road Initiative already in 2016. During the 2019 Belt and Road Forum (BRF), greening the Belt and Road Initiative has taken center stage.

The role of finance in protecting biodiversity and creating a green BRI can hardly be understated. Biofin can be broadly understood as employing instruments of finance to achieve the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal 15.

As such, biofin should be understood as part of green finance. Currently, most of green finance is employed to tackle climate change. According to the IDFC, of the 134 billion USD of green finance in 2018, only 9 billion went into non-climate finance specific investments. Similarly, the OECD found in their 2019 study that total investments in biodiversity protection – which include overseas direct investment, government funds and donations – was only about USD 80 billion, of which private investments were about 5-10 billion USD. That compares to a global bond market stock of USD 108 trillion USD and an expected Chinese bond issuances of USD 3 trillion in 2019.

There are a variety of challenges that make biodiversity finance difficult.

For investors, e.g.:

- Insufficient return on investments

- Insufficient liquidity of investment

- Unknown risk of investment

- Limited pipeline of projects

- Insufficient standards for evaluation

- Insufficient secondary markets

- High cost for ESIA and monitoring

For investees/projects, e.g.:

- No business case

- Limited knowledge and capacity regarding investor needs

- High cost of due diligence required by investors

- Difficulty to meet requirement for collateral, guarantees (e.g. also for ABS)

For regulators/governments, e.g.

- Limited legal basis for requiring biodiversity protection (e.g. to set incentives/safeguards)

- Limited capacity on appraising projects for biodiversity performance (esp. in emerging economies, BRI countries)

- Limited capacity in monitoring projects

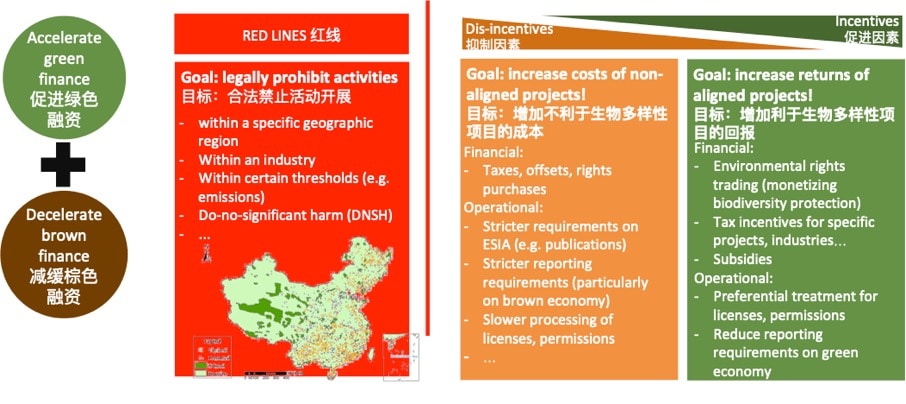

In order to accelerate protection of biodiversity through green finance, several steps are necessary – also in preparation for the CBD COP. First and foremost – brown finance has to be decelerated. That would include both subsidies into polluting industries (e.g. fossil fuels, agriculture) and stricter regulations and requirements (e.g. for licenses, reporting) for polluting industries. At the same time, green finance should be accelerated through a mix of increase of funding (e.g. tax incentives) and higher returns of projects (e.g. through subsidies, lighter regulation). In addition, China should share and expand its experience in “red-lining” landscapes in order to ideally protect key biodiversity areas (KBIs).

For responsible investors that means on the one hand to apply rigorous analysis of the impacts of their investments on biodiversity and possibly to engage in alleviating measures according to the IFC Performance Standard 6 and the EU’s Sustainable Investment Taxonomy. At the same time, biodiversity investors can employ business models that support protection or restoration of biodiversity, e.g.

- eco-tourism

- sustainable agriculture avoiding pesticide, herbicides and using natural protections

- green infrastructure (e.g. flood control through mangroves instead of concrete damns)

- payment for ecosystem services (PES) models, such as payment for protecting water sources rather than for cleaning of dirty water

A number of resources have been made available that can be helpful for investors to protect biodiversity and find business models in the Belt and Road Initiative:

- Natural Capital Coalition

- Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Network (BES-Net)

- The Biodiversity Finance Initiative (BIOFIN) of the UNDP

- Natural Capital Finance Alliance (NCFA)

- Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

- OECD and its database of biofinance instruments

- International Development Finance Club (IDFC)

- Coalition for Private Investment in Conservation (CPIC)

- NatureVest by The Nature Conservancy’s (TNC)

- The Little Biodiversity Finance Handbook by Global Canopy Project (GCP)

- …

However, looking at the current number of biodiversity protection and investments, large the knowledge and awareness gaps remain on all relevant levels in the investor community, with policy makers, and with the suppliers and project owners. In order to move to the next level, the following steps should urgently be taken:

- raise a broader awareness for biodiversity loss and biodiversity finance in the Chinese and BRI countries ministries of commerce, and ministries of finance

- raise a broader awareness with investors about threats of biodiversity loss and possibilities of safeguards for protecting biodiversity

- agree on broad stakeholder involvement for CBD COP that includes BRI

- set ambitious and relevant targets for CBD COP from the top policy levels.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.