Executive Summary

China is a major lender for countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, many of these countries have seen their sovereign debt become unsustainable. Based on the analysis of debt in 52 Selected BRI countries from 2014 to 2019, this brief presents the following findings:

- China’s newly-issued loans to the rest of the world have decreased significantly since 2018, however, with economic contraction due to Covid-19, existing loans are harder to service.

- Already in 2014, China was a major lender to these 52 BRI countries with US$ 49 billion in outstanding debt. By 2019, China’s total lending to these countries had doubled to US$102 billion, surpassing the sum of all other official bilateral creditors and reaching almost the same levels of lending by the World Bank;

- Debt to China as a share of Gross National Income (GNI) has increased particularly for the following countries: Republic of the Congo (from 13.62% in 2014 to 38.92% in 2019); Djibouti (from 7.71% to 34.64%); Angola (from 5.87% to 18.95%);

- At the end of 2019, among the 52 selected BRI countries, the five countries with the most outstanding debt owed to China are: Pakistan (US$20 billion), Angola (US$15 billion), Kenya (US$7.5 billion), Ethiopia (US$6.5 billion), and Lao PDR (US$5 billion);

- Since 2013, the majority of Chinese loans announced (but not necessarily disbursed) are for countries with the highest risk rating according to the OECD, such as Pakistan (about USD38 billion), Iran (about USD30 billion), or Venezuela (about USD24 billion);

- From 2021 to 2024, many countries will have to service significant amounts of Chinese debt, straining their ability for further investments, particularly Tonga, Djibouti, Cambodia, Angola, Republic of the Congo, Comoros and Maldives;

- China has made efforts to improve debt sustainability in debtor countries, but so far lacks a comprehensive debt relief strategy;

- China’s debt forgiveness has been less than 2% of debt owed;

- China needs to increase transparency of its lending including from policy banks for international debt relief and debt renegotiation programs to be effective;

- China has become an important partner for many BRI countries and has provided finance for future growth. China’s responsibility for sustainable development in these countries is increasing accordingly.

A Note on What We Analyze

There has been extensive research that focused on different aspects of debt sustainability issues in BRI countries and beyond. Among others, Center for Global Development published the report Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2018, evaluating debt sustainability of potential BRI borrowers and discussed Chinese practices on debt relief. The report Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery, published by Heinrich Böll Foundation, SOAS Centre for Sustainable Finance, and Global Development Policy Center in November 2020, proposes a comprehensive debt relief framework with participation of both public and private sectors to facilitate green recovery from Covid-19.

In this brief, we focus on recent developments of debt in Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries. We particularly aim to answer the following questions (especially in the 52 selected BRI countries): how large is China’s lending in BRI countries compared with other lenders? How did it evolve in the past few years and what’s the projection for the future? Are the risks for China’s overseas lending increasing? What China has done to manage the lending risks?

As China has not reported on the distribution of its loans among countries or regions, our country-level analysis is based on the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics (IDS). IDS include self-reported public debt data from 68 out of 73 eligible countries to the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), of which 52 are countries that have signed MoU with China to join the Belt and Road Initiative (see Appendix for a complete list). By analyzing debt statistics in the 52 selected BRI countries (out of over 130 in total), most of which are low-income and lower-middle-income countries, we identify some common trends as well as pattens that stand out in the bilateral borrowing with China.

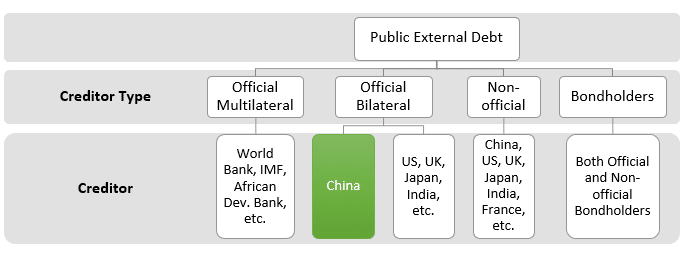

For a specific debtor country, IDS measure the overall aggregates and the composition of public external debt stocks by creditor type and by creditor (Figure 1). In the following analysis, we focus only on public external debt owed to Chinese official creditors (as marked in green in Figure 1), i.e. lending by Chinese governments and all public institutions in which the government share is 50 percent or above. Although a debtor country can also borrow from Chinese non-official lenders or by issuing bonds, they are both smaller in size and less affected by the debt restructuring or relief policies of the Chinese government.

Figure 1 Structure of the World Bank International Debt Statistics (IDS)

Source: IIGF Green BRI Center (2020)

Trends of China’s Overseas Lending

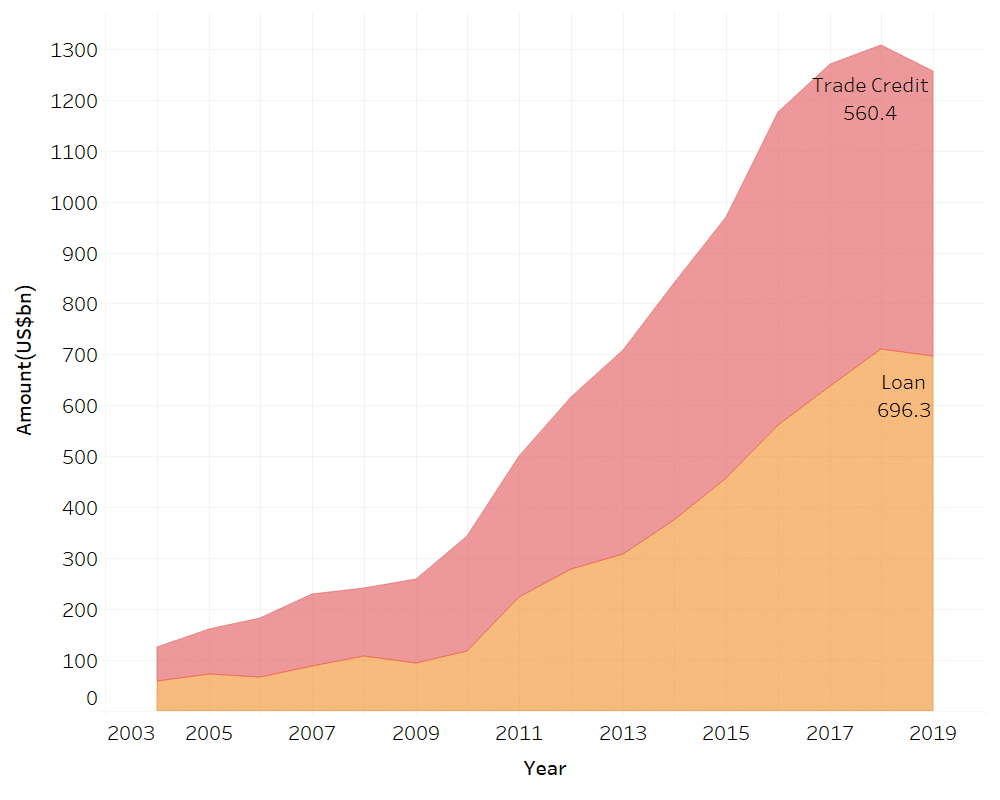

From 2004 to 2019, China’s overseas loans (that includes ALL foreign countries) grew by almost 12 times from US$59 billion to US$696 billion, accompanied by an increase of trade credit (referring to the account receivables of Chinese exporters plus prepayments by Chinese importers in international trade), which grew from US$67 billion in 2004 to US$560 billion in 2019 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 China’s Loans and Trade Credit, 2004-2019

Source: State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE); IIGF Green BRI Center (2020)

The official data from State Administration of Foreign Exchange of China (Figure 2) also shows that in 2019, the total unpaid loan was noticeably down from the 2018 level. One reason might be a collapse of overseas lending in 2018 and 2019 by two major policy banks of China — China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China — in the case of increased uncertainty abroad, as is shown by the latest data from Global Development Policy Center. However, even with the drop in newly-issued loans, the accumulated loans pose a significant strain to the balance sheets of these selected countries, as we analyze in this brief.

Public Debt in the BRI

Public debt has become a crucial topic for many BRI countries with several countries unable to service their debt or going into default (such as Zambia in November 2020). In the wake of covid-19 that led to a massive economic decline on the one hand with decreasing tax returns and exports and the need for government stimulus on the other hand, many governments have been struggling to find the necessary money to pay interests and principals on their external (and internal) sovereign debt.

In the wake of covid-19 that led to a massive economic decline, China has seen an increasing number of debt relief requests from BRI countries over the past months.

As the major lender in many of those countries, China has seen an increasing number of debt relief requests from BRI countries over the past months: In April, Pakistan hoped to renegotiate debt repayments to China after it alleged that Chinese companies had inflated power project costs; in August and September, Ecuador signed two deals to delay payments to China’s Exim Bank (US$474 million) and China Development Bank (US$417 million) after it struggled to service its debt because of a plunge of the oil price on which its exports partly depend; in September, Angola was close to finalizing a deal with Chinese creditors to restructure its US$20.1 billion of debts as it saw a gloomy economic outlook due to COVID-19 and an oil price slump. In October, Zambia hoped to have reached an agreement with China Development Bank (CDB) to defer its repayment to a US$391 million loan due in the same month, but the negotiations with the Export-Import Bank of China is still ongoing.

While Covid-19 has accelerated the struggles of many BRI countries to service its debt, the pressure for debt restructuring has been accelerating already before the Covid-19 pandemic. For example, in May 2019, China agreed to a debt restructuring deal with the Republic of Congo, extending debt repayment of US$1.68 billion by an additional 15 years.

For BRI countries, lending has been a major source of Chinese-led infrastructure development: in the BRI, many of the projects are financed by loans from Chinese financial institutions, such as China Development Bank (CDB) and Exim Bank of China. Among these loans, many are lent to, or guaranteed by BRI country governments.

Debt Outstanding to China from 2014 to 2019

Looking more specifically at different countries, the following interactive graph demonstrate the evolution of debt to GNI ratio in 52 selected BRI countries from 2014 to 2019. Debt-to-GNI ratio, according to the United Nations, measures the liabilities of a country in relation to its total income, and high and increasing debt ratios can be seen as an indication of unsustainable public finances.

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics; IIGF Green BRI Center (2020)

The results are as follows:

- Debt outstanding to China as a share of GNI (y-axis): as Chinese debt accumulated from 2014 to 2019, some countries had increased burden of fulfilling debt obligations to China. Republic of the Congo’s public debt to China as a share of GNI increased from 13.62% to 38.92%; for Djibouti, it increased from 7.71% to 34.64%; for Angola, it increased from 5.87% to 18.95%.

- Particularly worrying for their risk of default are countries that have a high public external debt outstanding to GNI ratio (x-axis): the ratio can be as high as 58% for Lao PDR, 62 % for Djibouti, and 60% for Republic of the Congo. Other countries, such as Samoa and Mozambique have moderate levels of debt owed to China, but their overall external debt levels are high compared with GNI, which might lead to similar cases as Republic of the Congo or Zambia with debt defaults likely.

- At the end of 2019, among the 52 selected BRI countries, top five countries with the most outstanding debt owed to China are: Pakistan (US$20 billion in debt outstanding), Angola (US$15 billion), and Kenya (US$7.5 billion), Ethiopia (US$6.5 billion) and Lao PDR (US$5 billion).

Particularly worrying for their risk of default are countries that have a high public external debt to GNI ratio, implying possible unsustainability in public finances.

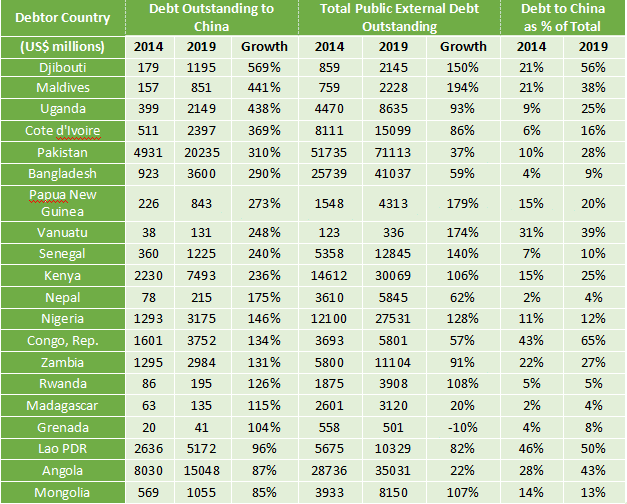

From 2014 to 2019, debt outstanding to China has grown relatively in proportion to total public external debt in some countries, but not in others.

- For Djibouti, Maldives, Uganda, Cote d’Ivoire and Pakistan, Republic of the Congo, debt to China has grown much faster than total debt, resulting in a much larger share of Chinese debt in total by the end of 2019.

- For Bangladesh, Nepal and Madagascar, debt to China also has a growth much higher that the total debt, but the share of Chinese debt in 2019 remained quite small.

- For Nigeria, Rwanda and Mongolia, debt to China grows at similar pace with total debt, maintaining a relatively low share of the total.

- Grenada’s total public external debt outstanding in 2019 has declined slightly from 2014, but its debt outstanding to China grew to twice of the 2014 level, though share of Chinese debt remained small.

Table 1 Comparison between Growths of Debt Outstanding to China and Total Public External Debt (Top 20 with highest growth of Chinese debt)

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics; IIGF Green BRI Center (2020)

One remarkable feature of China’s loans is that since 2013, the majority of Chinese loans announced (but not necessarily disbursed) are for countries with the highest risk rating according to the OECD, such as Pakistan (about USD38 billion), Iran (about USD30 billion), or Venezuela (about USD24 billion) (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 Loans Announced by China to Projects in BRI Countries, 2013-2020

Source: Financial Times

With both increasing loan exposure of these countries and due to the high risk of many of the debtor countries, China’s exposure to debt risks in some of these countries has increased massively.

China Compared to International Creditors

To better understand China’s responsibility and risks in regard to BRI country debt, we compare Chinese and non-Chinese loans in the BRI. As can be seen in Figure 4, from 2014 to 2019, the multilateral creditors group has remained the biggest lender to the 52 selected BRI countries compared the other creditor types, i.e. official bilateral creditors, bondholders, and non-official creditors.

Among other lenders, China was already a major one in these countries in 2014: With US$ 49 billion in outstanding debt, China alone accounted for about 16% of total official external debt, and 47% of that owed to official bilateral creditors. Japan followed with about 5% of total official external debt, and 14% of that owed to official bilateral creditors. By 2019, China’s total lending to these countries had nearly doubled to US$102 billion, almost the size of World Bank IDA (21% of total official external debt) and more than the sum of all other official bilateral creditors (62% of that owed to official bilateral creditors).

China is the largest bilateral creditor to these 52 BRI countries — larger than all other bilateral creditors combined.

Figure 4 Official External Debt Outstanding in 52 Selected BRI Countries by Creditors, 2014-2019

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics; IIGF Green BRI Center (2020)

When comparing Chinese to non-Chinese lending in specific countries (see the interactive graph below), a more differentiated picture emerges.

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics; IIGF Green BRI Center (2020)

In 2014, multilateral institutions were the major creditors in 30 out of the 52 selected countries, accounting for over 50% of their total public external debt. China was a prominent creditor for five countries:

- Tonga (Chinese debt was 63.79% of total),

- Lao PDR (46.45%),

- Republic of the Congo (43.34%),

- Cambodia (43.13%), and

- Tajikistan (40.37%).

The rest countries had different debt portfolios: loans from non-official creditors accounted for over 50% of Angola’s public debt; Myanmar saw 50.6% of its debt from official bilateral creditors other than China; Mozambique and Ghana had a more balanced composition of debt from multiple types of creditors.

From 2014 to 2019, China’s lending had outpaced other creditors in especially these countries: Djibouti, Comoros, Republic of the Congo, Angola, Maldives, Pakistan and Uganda.

Over the course of 5 years until the end of 2019, China’s lending had outpaced international lending in especially these countries:

- Djibouti: the share of Chinese debt increased from 20.80% to 54.91%; China replaced multilateral creditors group and became the largest lender;

- Comoros: the share of Chinese debt increased from zero to 28.36%; China caught up but still less than multilateral creditors such as IMF;

- Republic of the Congo: China’s share increased from 43.34% to 62.97%, and China has always been the largest creditor from 2014 to 2019;

- Angola: the share of Chinese debt increased from 27.94% to 45.77%, and similarly, China remained the largest creditor from 2014 to 2019;

- Maldives: the share of Chinese debt increased from 20.72% to 38.02%; China’s share was slightly higher than those of India, Asian Development Bank, and World Bank in 2014, but the difference had further widened by 2019.

- Pakistan: the share of Chinese debt increased from 9.53% to 25.55%; in 2014, Asian Development Bank and World Bank were the biggest creditors, and are still important lenders in Pakistan in 2019, together with China.

- Uganda: the share of Chinese debt increased from 8.93% to 24.22%; in 2014, World Bank was the single largest creditor, followed by African Development Bank. By the end of 2019, World Bank was still the largest, but China outpaced African Development Bank and became the second largest.

Meanwhile, some countries have seen a slight drop in the share of official bilateral debt owed to China:

- Ghana: the share of Chinese debt decreased from 16.22% to 11.20%. In 2014, World Bank was the largest creditor, about 1/5 of total debt outstanding, followed by China and bond market. By 2019, however, bond market had become the top source of external financing for the government of Ghana.

- Liberia: the share of Chinese debt decreased from 13.43% to 9.28%. The share of IMF debt also declined from 52.20% to 37.85%. World Bank outpaced other creditors and owns almost 1/3 of the official external debt of Liberia in 2019.

- Niger: the share of Chinese debt decreased from 18.98% to 12.90% from 2014 to 2019. The share of official bilateral debt dropped, while that of debt from multilateral lenders increased, such as World Bank.

Outlook for Debt Repayment

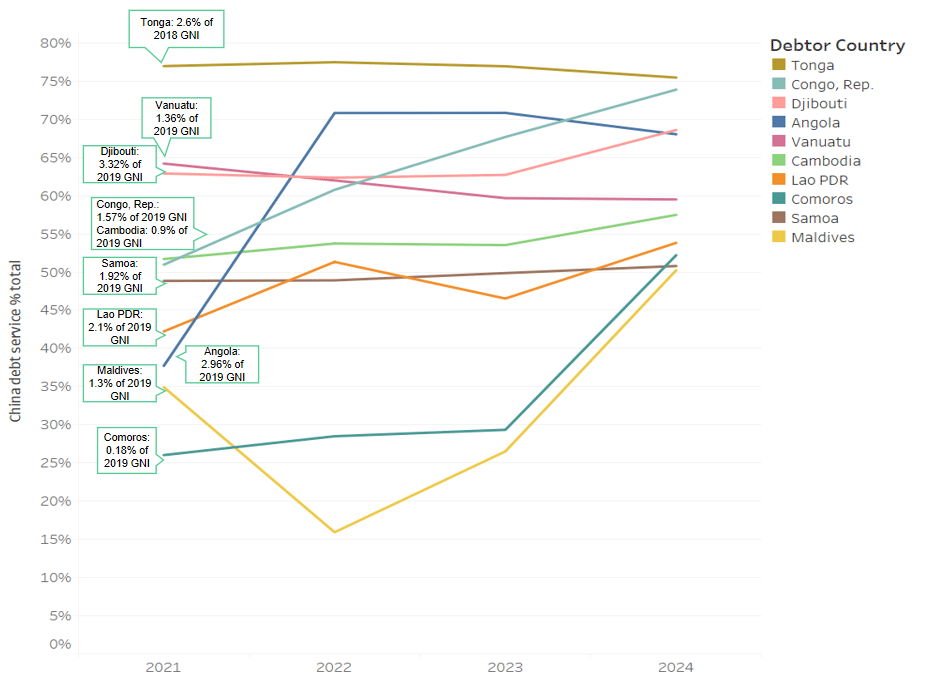

For the next several years, projected debt service to China as a percentage of total debt service remain low or moderate for most of the 52 selected BRI countries under analysis, but there are a few outliers (see Figure 5).

For countries such as Tonga, Djibouti and Cambodia, the shares of debt service to China will remain above 50% of total debt service. Despite the recent debt restructuring deals with China, Angola and Republic of the Congo will see the shares of debt service to China continue to rise to over 65% of their total public debt service. Comoros and Maldives also need to pay an increasingly large share of annual debt service to China in the next four years.

For governments of all these ten countries, debt repayment to China will constitute a significant share of their annual fiscal expenditure on paying off debt, making them particularly vulnerable and might require negotiations specifically with China in case of possible debt default.

Debt service to China in some BRI countries in the following years is expected to achieve 2% to 3% of GNI, about half of their public spending on education.

To provide an idea of the size of debt service to China in the 10 countries, Figure 5 also shows their debt service to China in 2021 as a percentage of GNI in 2019 (in 2018 for Tonga due to lack of data). For Djibouti, Tonga, Angola and Lao PDR, the percentage will be as high as 2% to 3%, which is equivalent to about half of their public spending on education.

Figure 5 Projected Debt Service to China as a Percentage of Total Debt Service in Selected BRI Countries (top 10)

Source: World Bank International Debt Statistics; IIGF Green BRI Center (2020)

China’s (Lacking) Debt Relief Strategy

Calls for debt relief have accelerated in 2020 in the wake of covid-19. However, with China’s loans having gone to high-risk countries before, China had previously collected some experience in dealing with debt default. Between 2000 and 2018, China approved 96 debt cancellations (including waiver, restructuring or rescheduling) (Figure 6). This, however only amounted to US$9.8 billion, mostly for interest-free loans and thus affected only a small fraction of less than 2% of China’s total loans.

Figure 6 China’s Debt Cancellations between 2000 and 2018

Source: Development Reimagined & Oxford China Africa Consultancy

Most Chinese debt cancellations benefited African countries, with Sudan, Angola, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Cote D’Ivoire having received three or more debt cancellations during this period (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Geographical distribution of Chinese debt cancellations

Source: Development Reimagined & Oxford China Africa Consultancy

With increasing debt issues, China’s Ministry of Finance released the Debt Sustainability Framework for Participating Countries of the Belt and Road Initiative in 2019, a non-mandatory framework for financial institutions to analyze debt sustainability and manage debt risks in low-income BRI countries.

Responding to the debt-challenges in the wake of Covid-19, China signed up to the Debt Service Suspendion Initiative (DSSI) under the G20 scheme to suspend bilateral loan repayments for 77 of the world’s poorest countries until the end of 2020. But China does not have a debt relief program like members of Paris Club and in past cases, preferred to grant debt relief bilaterally on a bespoke basis.

China does not have a debt relief program like members of Paris Club and in past cases, preferred to grant debt relief bilaterally on a bespoke basis.

The lack of a comprehensive debt relief strategy might be potentially risky for two reasons. First, past debt reliefs were manageable mainly because financial distress happened at country or regional level. As economies globally struggle to survive this year and most likely next year, the cost of negotiating dozens of debt-restructuring deals case by case will increase sharply for China and give rise to doubts on fairness and transparency among borrowers.

Second, despite its commitments to the DSSI initiative, there have been some controversies for China’s classifying SOEs and policy banks as non-official lenders and thus excluding a majority of its loans from this framework. Due to China’s significant size of debt outstanding overseas, the international community expects it to take bigger responsibilities including not only case-by case debts exemption, but also plans to address the development issues in the long term.

Conclusion and Outlook

China’s exposure to sovereign debt default in the BRI is increasing, especially in the aftermath of Covid-19 and in the several high-risk countries identified in the analysis above. China’s current strategies for dealing with debt relief requests, such as write-offs, terms renegotiation, deferment or asset seizure might work, but they create little value other than postponing the credit risks to the future.

To better manage potential debt risks in BRI countries and align China’s goal of “greening” the BRI, we recommend specifically to Chinese policy makers and financial institutions, such as CDB and China Exim Bank.

Recommendations for Chinese policymakers in the short term:

- for BRI countries with the highest exposure to Chinese debt, such as Djibouti, Republic of the Congo, Lao PDR, Kyrgyzstan and Angola, China should take the lead in designing emergency plans for debt relief in addition to the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative

- China should promote some level of “haircut” to its debt or debt reduction, to create fiscal space in these countries for fight the Covid-19 virus with clear stipulations to use the money rather to support a green recovery.

- For countries with manageable debt risks, China should coordinate with multilateral organizations, such as IMF and G20, on coordinated debt restructuring to avoid debt default and debt sustainability crisis and find a common deal among multiple investors

- China should clarify the role of China’s policy banks, particularly China Development Bank (CDB) and China Exim Bank.

Recommendations for Chinese policymakers in the long term:

- Focus on green infrastructure: as most of Chinese loans to BRI countries are related with large infrastructure or energy projects, China should take into consideration asset-level risks, in addition to country risks while issuing new loans or restructuring existing loans. This would accelerate a decrease in exposure to possible stranded assets, such as coal-fired power plants and hydropower plants that are prone to physical and transition risks, while it would accelerate investments in green energy projects, such as solar and wind.

- Improve debt governance by setting standards for overseas official lending. Domestically, strengthen debt transparency and develop coherent norms for major official Chinese lenders, such as China Development Bank (CDB) and China Exim Bank; internationally, embrace multilateral mechanisms for lending, such as increasing lending through AIIB.

- Develop and apply new debt mechanisms, such as debt for nature swaps, while trying to avoid contentious debt for resource swaps.

Appendix: 52 Selected BRI Countries Covered in the Analysis

| Country | Region | Income Group |

| Angola | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Bangladesh | South Asia | Lower middle income |

| Benin | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Burundi | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Cabo Verde | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Cambodia | East Asia & Pacific | Lower middle income |

| Cameroon | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Chad | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Comoros | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Congo, Rep. | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Côte d’Ivoire | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Djibouti | Middle East & North Africa | Lower middle income |

| Dominica | Latin America & Caribbean | Upper middle income |

| Ethiopia | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Fiji | East Asia & Pacific | Upper middle income |

| Gambia, The | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Ghana | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Grenada | Latin America & Caribbean | Upper middle income |

| Guinea | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Guyana | Latin America & Caribbean | Upper middle income |

| Kenya | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Kyrgyz Republic | Europe & Central Asia | Lower middle income |

| Lao PDR | East Asia & Pacific | Lower middle income |

| Lesotho | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Liberia | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Madagascar | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Maldives | South Asia | Upper middle income |

| Mali | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Mauritania | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Mongolia | East Asia & Pacific | Lower middle income |

| Mozambique | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Myanmar | East Asia & Pacific | Lower middle income |

| Nepal | South Asia | Lower middle income |

| Niger | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Nigeria | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Pakistan | South Asia | Lower middle income |

| Papua New Guinea | East Asia & Pacific | Lower middle income |

| Rwanda | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Samoa | East Asia & Pacific | Upper middle income |

| Senegal | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Sierra Leone | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Solomon Islands | East Asia & Pacific | Lower middle income |

| Somalia | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Tajikistan | Europe & Central Asia | Low income |

| Tanzania | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

| Togo | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Tonga | East Asia & Pacific | Upper middle income |

| Uganda | Sub-Saharan Africa | Low income |

| Uzbekistan | Europe & Central Asia | Lower middle income |

| Vanuatu | East Asia & Pacific | Lower middle income |

| Yemen, Rep. | Middle East & North Africa | Low income |

| Zambia | Sub-Saharan Africa | Lower middle income |

Mengdi Yue is a visiting researcher at the Green Finance & Development Center and previously was a researcher at the Green BRI Center at IIGF. She holds a Master in International Relations from School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) and has worked with the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), European Union Chamber of Commerce in China and the China-ASEAN Environmental Cooperation of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment. She is fascinated by green energy finance in China and the Belt and Road Initiative and data analysis.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.