The importance of relations between green finance and stimulus packages in concept and historically

Green finance policies and economic stimulus packages overlap at a number of levels. In an era where the global community faces both the immediate economic consequences of Covid-19 as well as the urgent need to transition to a low-carbon trajectory, it becomes critically important to be aware and to coordinate such relations. This tendency is true not only under domestic targeting of stimulus packages but also in an international context, where cooperation can be mutually beneficial.

Approaching the key areas of economic stimulus packages, we can see how these may impact green finance:

- Monetary stimulus: The primary tool in this category is cutting interest rates to increase borrowing, which consequently increases investment and consumption. However, without targeting interest rate reduction, this can lead to more business as usual, while we today need a low carbon transition. It can further create bubbles in some sectors that increase systemic risks. The same is valid for reducing capital reserve requirements for banks.

- Fiscal stimulus: This tool covers reducing taxes and increasing government spending. The tool is a more straightforward mechanism to target green economic sectors than interest rates, as taxes can be reduced on particular industries and increased in others. Fiscal spending in stimulus packages is often aimed at infrastructure, and this is a natural area to both use minimum environmental standards and concrete proportions allocated for green activities.

- Quantitative easing: This tool involves using the government’s capital to buy assets on financial markets, to support market stability and decrease the cost of capital. While being targeted broadly at the financial system in the past, it is possible to also focus these efforts on green areas such as by ESG indicators or industrial sectors.

Some of these relations can be explicitly seen in previous examples of stimulus packages from different countries and regions. The US 2008 economic stimulus package, called the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, totaled USD 787 billion and was comprised of about a third each for tax cuts, federal spending, as well as social security. Focused on supporting the economy as a whole, little emphasis was put on other policy targets such as sustainability and climate change, with energy efficiency and renewable energy research only making up 3,4%. The EU’s 2008 European Economic Recovery Plan amounted to EUR 200 billion spread across all 27 member countries. The plan included the same three components as the US, while emphasizing sparking investment in infrastructure addressing climate change. The EU plan was also one of the first large scale applications of quantitative easing. The 2008-09 Chinese economic stimulus plan allocated USD 586 billion, with the majority going towards infrastructure, rural development, and industry, with 5,3% allocated specifically to energy saving, gas emissions cuts, and environmental engineering projects. All the above cases simultaneously reduced interest rates indiscriminately, allowing banks to lend to the economy as a whole.

Contents of current EU stimulus package and its relations to green finance

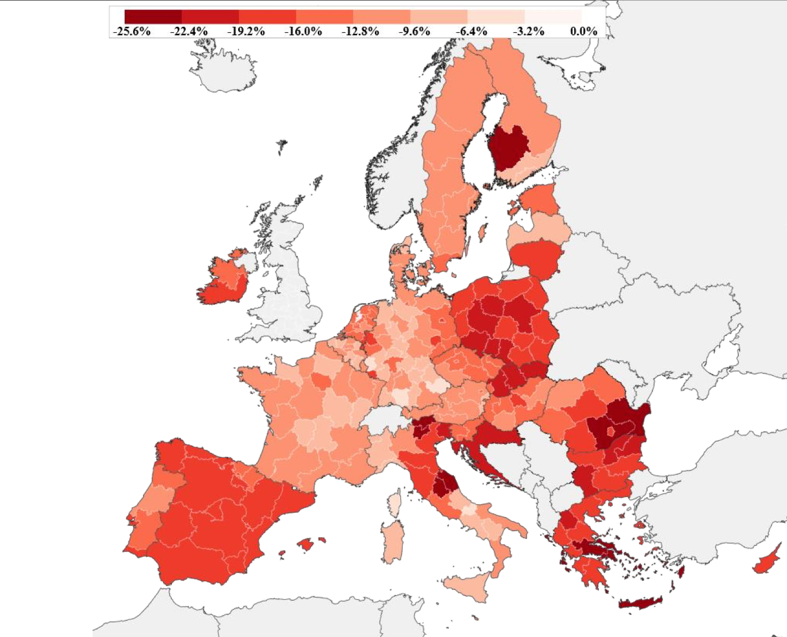

As of early July 2020, European countries remain to formally agree on the stimulus package, though most things outlined in the proposal from late May are expected to stay in place. The main sticking point remaining is how large the grant component should be, with some countries arguing that all support should be in the form of loans. The proposal at present includes USD 500 billion in grants and the rest in loans. The current proposal amounts to USD 847 billion (EUR 750 billion), for which most capital would be raised on public capital markets. The capital will be distributed based on needs, with about 20% each for Italy and Spain, with only10% for France and 7% for Germany. That logic is based on the uneven economic impacts, as shown in figure 1 below. Similarly, not all sectors of the economy are impacted equally, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 1: GDP changes across EU countries, without any policy measures (Source: European Commission)

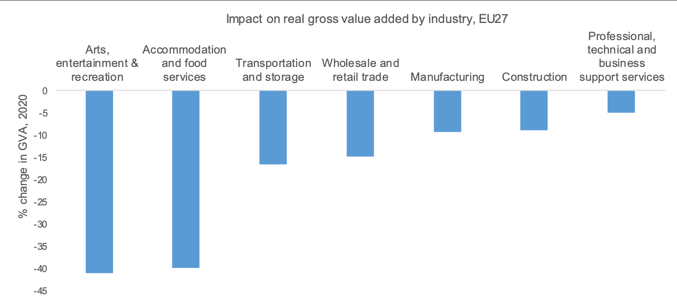

Sustainability and climate issues are at the core of the package, as of the European Parliament: “The funds will be used to reach the EU’s objectives of climate neutrality and digital transformation, to offer social and employment support as well as to reinforce the EU’s role as a global player.” Allocation of the financial support between sectors remain to be settled in detail but will be based on the EU’s assessment of financing gaps in each sector, as shown in figure 3 below. Renewable energy makes up the second-largest single category, while 25% will be allocated to climate-friendly activities, such as building renovation, clean energy technologies, low-carbon vehicles, and sustainable land use.

Figure 3: Basic investment needs (Source: European Commission)

| Tourism | 161 |

| Mobility-Transport-Automotive | 64 |

| Aerospace & Defence | 4 |

| Construction | 54 |

| Agri-food | 32 |

| Energy Intensive Industries | 88 |

| Textile | 6 |

| Creative & Cultural Industries | 6 |

| Digital | 66 |

| Renewable Energy | 100 |

| Electronics | 18 |

| Retail | 115 |

| Proximity & Social Economy | N/A |

| Health | 32 |

| TOTAL | EUR 748 billion |

The three components of the EU stimulus package are 1) supporting member states with investment and reforms, 2) Kick-starting the EU economy by incentivizing private investments, and 3) Addressing the lessons of the crisis. Most funds will be used to support member states’ government budgets in order to increase fiscal spending. Tax cuts have not been prioritized so far, and quantitative easing has not been considered as a prioritized part of the package.

From a green finance perspective, the most relevant components are the following:

- A new Recovery and Resilience Facility of €560 billion will offer financial support for investments and reforms, including in relation to the green and digital transitions and the resilience of national economies, linking these to the EU priorities. This facility will be embedded in the European Semester. It will be equipped with a grant facility of up to €310 billion and will be able to make up to €250 billion available in loans. Support will be available to all Member States but concentrated on the most affected and where resilience needs are the greatest.

- A proposal to strengthen the Just Transition Fund up to €40 billion, to assist Member States in accelerating the transition towards climate neutrality.

- A €15 billion reinforcement for the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development to support rural areas in making the structural changes necessary in line with the European Green Deal and achieving the ambitious targets in line with the new biodiversity and Farm to Fork strategies.

- A new Solvency Support Instrument will mobilize private resources to urgently support viable European companies in the sectors, regions, and countries most affected. It can be operational from 2020 and will have a budget of €31 billion, aiming to unlock €300 billion in solvency support for companies from all economic sectors and prepare them for a cleaner, digital and resilient future.

- Upgrade InvestEU, Europe’s flagship investment program, to a level of €15.3 billion to mobilize private investment in projects across the Union.

- A new Strategic Investment Facility built into InvestEU– to generate investments of up to €150 billion in boosting the resilience of strategic sectors, notably those linked to the green and digital transition, and key value chains in the internal market, thanks to a contribution of €15 billion from Next Generation EU.

From the above, it is clear that the EU’s stimulus package will mainly be rolled out through increasing member countries budgets as well as through designated funds for various purposes. Both have clear implications for green finance. At the member country level, greenness is ensured by the proposed 25% climate allocation as well as through the EU’s green new deal, ensuring investment is Paris alignment. Most of the funds themselves also have clear green objectives and safeguards. It is consequently clear that the EU aims to use the stimulus package not to provide an economic boost towards business-as-usual, but rather to push the economy in a sustainable direction. For green finance, this is a positive development increasing its importance as a tool to drive a low-carbon transition. With the EU’s Sustainable Finance Action Plan providing guidance, regulations, and standards from 2020, then timing is right to make a strong push for mainstreaming green finance in the EU’s financial system.

Possibilities for EU-China economic stimulus coordination in general and in the BRI

The EU and China can coordinate their responses to COVID-19 through green stimulus packages. As both countries are using the financial system as a critical tool to support their economies, as opposed to pure fiscal spending, these stimulus packages are a crucial opportunity to spur green financial systems. So far, this pandemic has not led to the kind of coordination of stimulus packages between G20 countries that followed the 2008 global financial crisis. If the EU and China were to coordinate their responses more systematically, this would likely incentivize other G20 members to participate.

China and the EU can build upon existing efforts, including the Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). This platform could function as an avenue to coordinate greening stimulus measures, including quantitative easing, greening macroprudential assessment of commercial banks, or reducing risk weighting of green assets. With a joint push from the EU and China, such efforts could ensure that stimulus packages are aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Ultimately, even outside the context of stimulus packages, the NGFS provides an important way to learn from each other’s experiences and coordinate efforts. Positive results could create momentum for other countries to follow suit.

Furthermore, both the EU and China should

launch joint efforts in third countries. Key frameworks for such collaboration

are the Belt and Road Initiative on the Chinese side, and the Connecting Europe

and Asia Strategy on the European side. In practice, cooperation based on these

frameworks takes place within the China-EU Connectivity Platform and the

China-EU Co-Investment Fund. Nonetheless, while these initiatives are

well-intentioned, the practical results have so far been limited. Such

ambitions should be prioritised further; infrastructure projects such as

railways and electricity networks could boost the connectivity between EU,

China, and all countries in between. An ideal method to encourage this would be

to start with co-financing between the European Investment Bank and the China

Development Bank. This would catalyse private and commercial investment in both

the EU and China’s financial systems. This effort can build upon current

bottom-up initiatives such as the BRI Green Investment Principles, which

provide a set of guidelines to ensure environmental sustainability, and whose

founding members consist of primarily EU and Chinese financial institutions.

Mathias Lund Larsen is non-resident research fellow at the Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University. He is also a dual PhD Fellow at Copenhagen Business School and the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Sino-Danish Center for Education and Research). His research is focused on the political economy of green finance in China from theory to practice, intention to impact, and domestic to overseas.

He has spent more than a decade working on the intersection between China, sustainability, and finance, and speaks fluent Chinese. He has previously held positions in the UN in New York, Nairobi, Bangkok, and Beijing and holds two double Masters degrees in and around political economy from Copenhagen Business School, Rotterdam School of Management, Sciences Po Paris, and Peking University.

Comments are closed.