1. The importance of relations between green finance and stimulus packages in concept and historically

Green finance policies and economic stimulus packages overlap at a number of levels. In an era where the global community faces both the immediate economic consequences of Covid-19 as well as the urgent need to transition to a low-carbon trajectory, it becomes critically important to be aware and to coordinate such relations. This tendency is true not only under domestic targeting of stimulus packages but also in an international context, where cooperation can be mutually beneficial.

Approaching the key areas of economic stimulus packages, we can see how these may impact green finance:

- Monetary stimulus: The primary tool in this category is cutting interest rates to increase borrowing, which consequently increases investment and consumption. However, without targeting interest rate reduction, this can lead to more business as usual, while we today need a low carbon transition. It can further create bubbles in some sectors that increase systemic risks. The same is valid for reducing capital reserve requirements for banks.

- Fiscal stimulus: This tool covers reducing taxes and increasing government spending. The tool is a more straightforward mechanism to target green economic sectors than interest rates, as taxes can be reduced on particular industries and increased in others. Fiscal spending in stimulus packages is often aimed at infrastructure, and this is a natural area to both use minimum environmental standards and concrete proportions allocated for green activities.

- Quantitative easing: This tool involves using the government’s capital to buy assets on financial markets, to support market stability and decrease the cost of capital. While being targeted broadly at the financial system in the past, it is possible to also focus these efforts on green areas such as by ESG indicators or industrial sectors.

Some of these relations can be explicitly seen in previous examples of stimulus packages from different countries and regions. The US economic stimulus package in 2008, called the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, totalled USD 787 billion and was comprised of about a third each for tax cuts, federal spending, as well as social security. Focused on supporting the economy as a whole, little emphasis was put on other policy targets such as sustainability and climate change, with energy efficiency and renewable energy research only making up 3,4%. The EU’s European Economic Recovery Plan in 2008 amounted to EUR 200 billion spread across all 27 member countries. The plan included the same three components as the US, while emphasizing investment in infrastructure addressing climate change. Green parts cumulatively made up 13,2%. The EU plan was also one of the first large scale applications of quantitative easing. The 2008-09 Chinese economic stimulus plan allocated USD 586 billion, with the majority going towards infrastructure, rural development, and industry. 5,3% were assigned specifically to energy saving, gas emissions cuts, and environmental engineering projects. All the above cases simultaneously reduced interest rates indiscriminately, allowing banks to lend to the economy as a whole.

2. Contents of current US stimulus package and its relations to green finance

Covid-19 has had a substantial negative impact on the global economy, with 52% of executives globally saying their national economies are doing ‘substantially worse’ in June, up from just 10% in March.

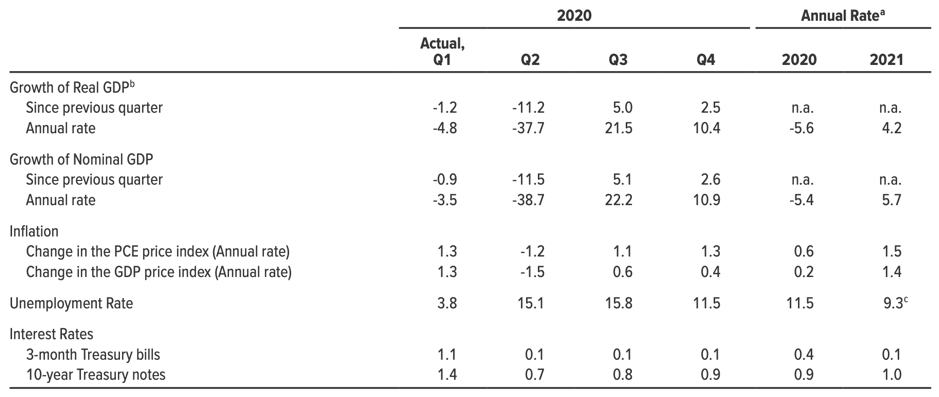

The US economy is, of course, no exception to this trend. According to the Congressional Budget Office’s May 2020 report, the repercussions can be seen directly across several areas:

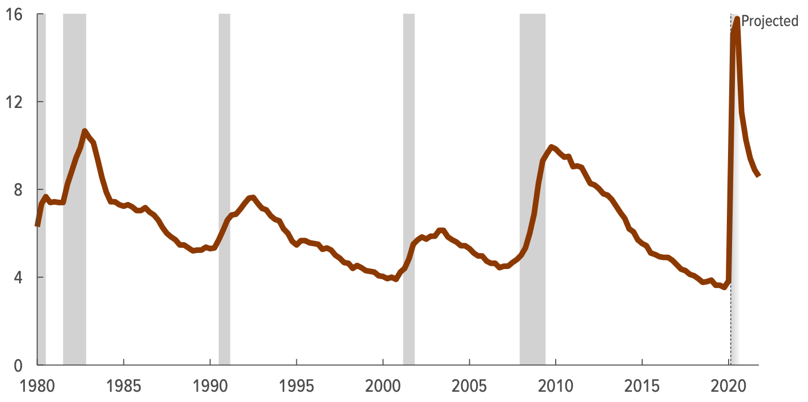

- The unemployment rate increased from 3.5% in February to 14.7% in April, representing a decline of more than 25 million people employed, plus another 8 million persons that exited the labor force. The unemployment rate was forecast to average 11.5% in 2020 and 9.3% in 2021.

- Real (inflation-adjusted) consumer spending fell 17% from February to April, as social distancing reached its peak. In April, car and light truck sales were 49% below the late 2019 monthly average. Mortgage applications fell 30% in April 2020 versus April 2019.

- Real GDP is forecast to fall at a nearly 38% annual rate in the second quarter, or 11.2% versus the prior quarter, with a return to positive growth of 5.0% in Q3 and 2.5% in Q4 2020. However, real GDP is not expected to regain its Q4 2019 level until 2022 or later.

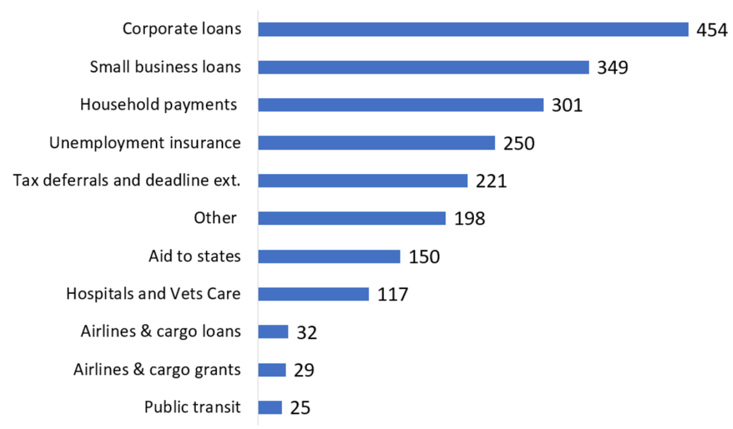

As a response to this economic crisis resulting from the global Covid-19 outbreak, the US congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act on 25th March 2020. As the largest economic stimulus package in US and world history, it amounts to about USD 2 trillion, equivalent to 10% of US GDP. The budgetary impacts include USD 988 billion increase in mandatory outlays, USD 446 billion decrease in revenues, and USD 326 billion increase in discretionary outlays. As shown in figure 3, the package covers a broad range of areas, targeting both businesses, individuals, and social security.

While the size is tremendous, the green ambitions of the stimulus package are not. While Democrats tried to include climate-friendly provisions in the early stages of drafting the package, these were rejected by Republican counterparts. A compromise was found in agreeing not to bail out fossil fuel companies, and the package was agreed with bi-partisan support. Estimates from climate change researchers suggest that the US package does not include any direct green or climate commitments, except for USD 900 million for the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) that helps households heat and cool their homes. As we can see from the relief amounts by category, the overall layout of the package is also not focused on infrastructure investment, as those of other countries often are. That in itself limits the direct possibility to channel investments into infrastructure within low-carbon energy, transport, or agriculture. While a distinct and separate USD 1 trillion stimulus package for infrastructure has been considered in June 2020, details are sparse on its contents, and it’s difficult to estimate the likelihood of its realization.

3. Possibilities for US-China cooperation in the context of green finance in economic stimulus packages

Despite the meager green ambitions in the US economic stimulus package, surrounding trends mean that the situation can still bring about green finance development and cooperation with China.

First, each country can increase green investment in each other’s’ country. Despite limits on ownership of specific strategic industries and companies, investment back and forth has increased gradually over the past years. Recent examples facilitating this trend on the Chinese side include removing quotas for the Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor scheme, allowing foreign majority ownership of asset management companies, and setting up more stock and bond connect schemes. On the US side, MSCI’s inclusion of Chinese A-shares in its emerging market index and Goldman Sachs rapid expansion in China show a similar interest. Green and ESG components can easily be built upon these trends, as awareness of such issues is simultaneously gradually increasing amongst investors on both sides. The success and continuous expansion of the US-China Green Fund is an exemplification of the possibilities for such cooperation.

Second, the US and China can coordinate their responses to COVID-19 through green stimulus packages. As both countries are using the financial system as a critical tool to support their economies, as opposed to pure fiscal spending, these stimulus packages are a crucial opportunity to spur green financial systems. So far, this pandemic has not led to the kind of coordination of stimulus packages between G20 countries that followed the 2008 global financial crisis. If the US and China were to coordinate their responses more systematically, this would likely incentivize other G20 members to participate. This is difficult so far, with limited green components in the US package, though this may change if an infrastructure specific package is rolled out.

Third, both countries are key investors in BRI countries, including in sustainable infrastructure. Though limited cooperation has taken place in terms of joint project financing or construction, this becomes increasingly possible as Chinese project involvement opens up to working with more non-Chinese partners. It is happening in particular in renewable energy, as recently seen in JinkoSolar’s participation in the world’s largest PV project in Abu Dhabi, both providing solar panels and holding a 20% equity stake. The project has involvement from Indian EPC contractors (Sterling and Wilson), a Japanese electrical company (Marubeni), and several European banks (Natixis, Credit Agricole, and BNP Paribas). Despite no American participation, the project example highlights a trend for Chinese companies to be part of international project setups, that American companies could also be part of in the future.

Mathias Lund Larsen is non-resident research fellow at the Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University. He is also a dual PhD Fellow at Copenhagen Business School and the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Sino-Danish Center for Education and Research). His research is focused on the political economy of green finance in China from theory to practice, intention to impact, and domestic to overseas.

He has spent more than a decade working on the intersection between China, sustainability, and finance, and speaks fluent Chinese. He has previously held positions in the UN in New York, Nairobi, Bangkok, and Beijing and holds two double Masters degrees in and around political economy from Copenhagen Business School, Rotterdam School of Management, Sciences Po Paris, and Peking University.

Comments are closed.