This article was originally published in The World Financial Review.

The green transition of energy, transport, industry, urbanisation and agriculture requires a massive acceleration of global green investments across the world to meet the Paris agreement and reverse the loss of biodiversity. Yet so far, green finance lacks harmonised definitions regarding types of underlying assets, disclosure requirements, impact thresholds and applicable instruments. This makes international green finance flows, disclosure, and risk management incomplete, while providing fertile ground for “greenwashing”.

As two of the major markets for green finance, China and the European Union have been cooperating to develop shared standards, most recently by launching a comparison and roadmap for compatibility. The cooperation is based on the 2005 EU-China Partnership on Climate Change, which has provided a high-level political framework for cooperation and dialogue. This commitment has been confirmed and enhanced on several occasions (e.g., 2010 Joint Statement, 2015 Joint Statement, 2018 Leaders’ Statement)1. In 2020, Chinese President Xi, European Council President Michel, European Commission President van der Leyen, and European Council President German Chancellor Merkel discussed shared ambitions for cooperation on increasing climate ambitions and established a High-Level Environmental and Climate Dialogue during the EU-China Leaders Meeting. Yet, with global political tensions rising, progress on green finance cooperation between China and the EU has hit a roadblock.

As the most active on green finance policy making, the EU and China must cooperate in particular on taxonomies, emissions trading, and their global engagements.

The importance of green finance harmonisation for the EU and China

Green finance is considered a key element in tackling the dual challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss. It aims to provide relevant incentives to accelerate investments in green economic activities and, ideally, accompanying disincentives to reduce and phase out harmful investments. Harmonisation of green finance is accordingly relevant for two reasons. First, environmental risks, particularly climate risks, are global and therefore need to be tackled on a level playing field. Second, harmonised standards allow accelerating capital flows and, in particular, cross-border capital flows. As the majority of global capital is owned by western organisations, facilitating the flow to the global South is critical.Besides the harmonisation of Chinese and European green finance standards, both countries are also cooperating in supporting green finance development globally.

This need to mobilise capital for a green transition makes EU-China cooperation on green finance particularly important. China considers itself the largest developing country, and the EU as a single market is the largest green finance market in terms of bond issuance and ESG funds. China, through its green credit system, bond markets, and related taxonomies, its emissions trading system (ETS), and similarly the European Union through its Sustainable Finance Taxonomy and Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation, as well as its ETS, have set global standards and developed the largest green finance markets in the world. For future alignment with its green growth goals, the EU also launched public consultations for a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) in July 2020, with continued progress on its design.

Despite important milestones, such as the Common Ground Taxonomy introduced in November 2021 under the leadership of China and the EU, frictions still exist. For example, international investors still face challenges accessing China’s green financial markets. Principally, China still has capital market restrictions through investment approval systems, no direct access to the bond market, but the requirement to go through the bond and stock exchange connects.

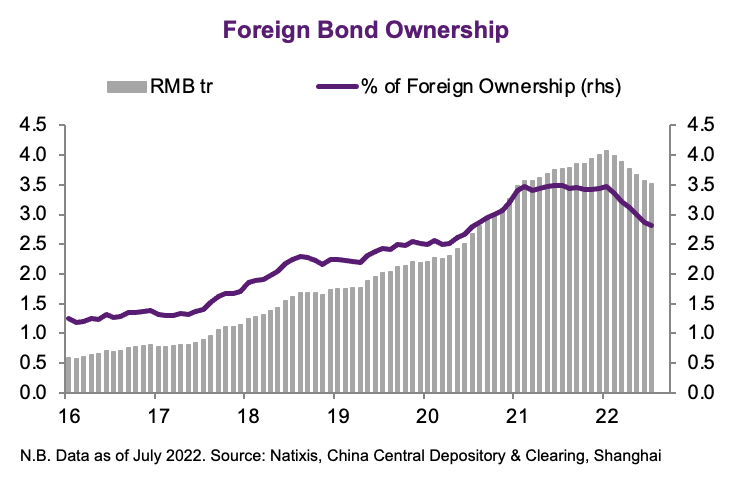

This has also led to outflows of international funds from China in the early months of 2022, keeping the already low share of foreign holdings of Chinese bonds at a low 3.2 per cent in China’s bond market and 4.2 per cent in the stock market (see figure 1)2,3.

Challenges also persist in cooperating in international financing due to strategically non-aligned interests between China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the EU’s Global Gateway strategy. To overcome frictions between green financial systems and allow for more green finance flows, China and the European Union have particularly worked on harmonising their green finance taxonomies, with some success, and on cooperation with regard to carbon pricing through emissions trading systems4.

EU-China green financial markets integration through green taxonomies

Since its initial publication in 2015, China’s green bond catalogue has encouraged “green” investments in “clean coal” – undermining the EU green finance taxonomy goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. To coordinate their green financial systems, the PBoC published an updated green bond catalogue in April 2021 that removed the construction of new “clean coal”power plants, but kept upgrading different types of coal usage. The catalogue also adjusted the categorisation system to match the EU Taxonomy, and the adoption of the EU “Do No Significant Harm” principle to avoid investing in climate-friendly but biodiversity-destroying assets was discussed. Yet, gaps still exist.

The EU Taxonomy focuses on the environmental impacts of activities through the provision of specific thresholds for climate mitigation, compared to a project list in the Chinese green bond catalogue5. The EU Taxonomy’s agriculture-related criteria focus more on greenhouse gas reduction and less on broader sustainable farming aspects that may be relevant in other markets, including China’s. This includes reduced use of pesticides, the adoption of biodiversity-friendly techniques, and water conservation. The EU Taxonomy includes six environmental objectives, which are interlinked through the multidimensional ‘Do No Significant Harm’ requirement. In comparison, China’s green bond catalogue does not explicitly define any environmental objectives 6. The EU Taxonomy also recognises three different types of environmentally sustainable economic activities: sustainable, transition, and enabling activities 7. By contrast, the green bond catalogue does not include transition and enabling activities8.The EU and China could strengthen cooperation in providing macro- and micro-prudential risk frameworks, such as for biodiversity loss stress testing, as well as common taxonomies and reporting standards.

To overcome the difference, China and the EU have led the development of the “common ground taxonomy” (CGT), which was introduced at COP 26 in November 20219. However, the CGT currently provides a comparison of the taxonomies and not a common ground taxonomy, despite the name. As such, the CGT does not address the concerns of European investors who will have to disclose their Chinese investments in accordance with the EU’s regulation on sustainability-related disclosures in the financial services sector (the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation – SFDR). Nor does it present proposals to increase compatibility or expand interoperability. Rather, the CGT simply provides a comparison between the green part of the EU taxonomy and the Chinese green bond taxonomy. Furthermore, the two taxonomies compared in the CGT are only two of numerous current and forthcoming taxonomies. In the EU, the current taxonomy only covers green aspects, with social and broader sustainability aspects to be added over the coming years. In China, taxonomies differ by the regulator, economic sector, financial instrument, and sustainability focus. For example, China has launched a climate taxonomy and social taxonomy with overlaps and differences compared to the green bond taxonomy. This myriad of taxonomies means that the CGT is only a narrow comparison of the two most prominent taxonomies, with limited consideration of the broader context.

Emissions Trading

A focus of EU-China cooperation has been emissions trading mechanisms. From 2014 to 2017, the EU supported the design and implementation of emissions trading in China (based on the 2015 Joint Statement). The EU provided technical assistance for capacity building and supported the seven regional pilot systems, as well as the establishment of the national emissions trading system. The project has been extended into the “Platform for Policy Dialogue and Cooperation between EU and China on Emissions Trading” (2017-20), which supports the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) in its efforts to implement and further develop China’s national ETS and established a policy dialogue between the MEE and the European Commission. China and the EU signed an MoU to enhance cooperation on emissions trading at the 2018 EU-China Summit10.

In 2021, China’s national ETS was launched, coinciding with the EU’s announcement of its carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) that would price the import of carbon emissions into the EU. While the launch of the China ETS was welcomed by the EU, the mechanisms of the Chinese and the EU ETS are not aligned. The Chinese ETS continues to be “intensity-based”, with fewer sectors, high allowances, and no communicated pathway to emission reduction, while the EU ETS is a cap-and-trade system with a clearly communicated emission reduction of emissions allowances. Also, the price of allowances varies widely by a factor of 10, making Chinese emissions much cheaper compared to EU emissions, even in the few sectors included in China’s ETS. This, potentially, has also led to China’s resistance to the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) work to price the import of carbon emissions into the EU.

The global importance of EU-China coordination

Besides the harmonisation of Chinese and European green finance standards, both countries are also cooperating in supporting green finance development globally. China and the EU, together with relevant authorities from Argentina, Canada, Chile, India, Kenya, and Morocco, had also launched the International Platform for Sustainable Finance (IPSF) in October 2019 11. The IPSF aims to scale up the mobilisation of private capital towards environmentally sustainable investments and to offer a multilateral forum of dialogue between policymakers who are in charge of developing sustainable finance regulatory measures to help investors identify and seize sustainable investment opportunities that truly contribute to climate and environmental objectives. The IPSF now includes 18 members11. Besides the IPSF, the PBoC and the EU Commission were founding members of the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) 12. The NGFS’s goal is to contribute to the development of environment and climate risk management in the financial sector.

With strong green finance track records, Chinese and EU institutions are also working together to share green finance experiences learnt across Asia. For example, in 2019, Tsinghua University supported the development of the Mongolia Green Taxonomy, while the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development supported Mongolia’s green capital market development in 202113.

A call to action – climate change will not wait

With China and the EU firmly committed to building a green economy, the cooperation on green finance should be further strengthened. Against the backdrop of continuing economic challenges after the COVID-19 pandemic, increased uncertainty of international trade and other political challenges, combating climate change and accelerating green finance is a strategic and shared interest of all countries. Stepping up Sino-EU cooperation and action will provide both sides with significant opportunities for modernising their economies, enhancing competitiveness, and ensuring socio-economic benefits of increased clean energy access.

With the goal to accelerate the international flow and use of green finance, the EU and China could, therefore, particularly work on green policy harmonisation to define the regulatory scope of climate action and send clear signals to investors about political ambitions. This should also include green finance standard harmonisation, particularly for common definitions of green products and services, common procedures for verification of green finance products, common standards for reporting (e.g., TCFD) and possibly a standard for “dirty finance”. As China’s capital markets are still “opening up”, harmonisation could improve the attractiveness of markets through easier access, particularly for European investors, to the Chinese market in addition to the Bond Connect programme and increase the liquidity of Chinese bond markets. To reduce non-green finance, the EU and China, as two of the largest global emitters, should further cooperate on utilising emissions trading systems and other carbon markets. This could also include collaboration on avoiding carbon leakage, possibly through a “just” EU carbon border adjustment mechanism that provides development finance for carbon reduction, and through participation in multinational carbon markets.

The EU and China should further strengthen collaboration on biodiversity finance as one area where global green finance standards are just starting to evolve. The EU and China could strengthen cooperation in providing macro- and micro-prudential risk frameworks, such as for biodiversity loss stress testing, as well as common taxonomies and reporting standards. While challenges in cooperation might continue, policymakers and financial institutions should welcome and support China-EU green finance harmonisation. Meanwhile, investors should not use a lack of harmonisation as an excuse for a lack of green finance action. Climate change will not wait.

Comments are closed.