This article is the first of a three part series on green finance trends in China:

- The first part focused on China’s green finance policy and system

- The second part focused on trends in different green finance instruments (e.g., green bond, green credit, ESG).

- This third part focuses on trends and recommendations for 2023 and beyond.

The work was prepared with support from the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) as a scoping study for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED). The report does not reflect official positions from either of the organizations.

Trends in green finance in China

In 2022 and likely in 2023, China’s focus will lie on economic growth to offset significant risks in the aftermath of COVID-related lockdowns, real estate challenges, and geopolitical shifts and risks. China’s ambition for technological self-reliance is poised to accelerate investments in high-technology products and technologies, some of which are in the green economy space (e.g., new energy vehicles, and renewable energy). At the same time, China’s economic policy risks further investments in fossil fuels supposedly to ensure energy security. Furthermore, China’s ambitions seem to point to strategic collaboration with aligned countries, e.g., in the Belt and Road Initiative, and strategic dependence and independence from non-aligned countries, for example, in trade, investments, and finance.

In this larger picture, specific areas of green finance that seem to gain prominence based on an analysis of recent speeches by leading policy makers and think tanks include:

- Transition finance is likely to become China’s priority in developing green finance. During the Fifth Hongqiao International Economic Forum, Vice Governor Xuan Changneng emphasized “steady transformation of high-carbon industries such as coal and low-carbon transition is also an important part of achieving carbon neutrality. Some carbon-intensified industries cannot obtain the funds needed for the transition from the existing green financial system as they do not belong to the green category “. Xuan further stated that in the future, the People’s Bank of China will improve the effective connection between green finance and transition finance and apply successful practices and experiences of green finance to support transition activities.[1]. With the uncertainty of economic development and energy security, China emphasizes energy security as a top priority. In this regard, transition finance can be an important funding source to support transitioning current carbon-intensified sector transit to green. The Green Finance Committee of China will actively explore a transition catalogue.

- Disclosure requirements and corresponding supervision are likely to be marked in China’s future work to expand its green finance market and attract global investors. In an interview in June 2022, Yi Gang, governor of PBOC, raised concern about “moral hazards” and warned against “greenwashing, low-cost fund arbitrage, and green project fraud”[2]. The central bank also released an English version of Yi ‘s comments, a signal of appeal to international audiences.

- International cooperation on green finance. Multiple speeches delivered by policymakersemphasized China’s continuing effort in international green finance cooperation. GFC will support the wider application of the Common Taxonomy, both domestically and internationally, and aims to expand the influence of Green Investment Principles (GIP) over the Belt and Road area (GIP established its first African branch during COP27 and will also prepare for the GIP Southeast Asia branch). China will also continue to support the sustainable finance work with G20, the ISSB for ESG standards, and the IPFS.

Barriers and Recommendations to accelerate green finance in China

Barriers for green finance in China

China’s regulators and related government bodies have provided innovative and ambitious guidelines, guidance, opinions, as well as tools to accelerate green finance applications. This has provided an impetus for the application of various green financial instruments (e.g., bonds, credit), ESG disclosure, and risk management. Financial sector players have picked up on these policy signals and improved environmental (and social) disclosure practices. Overall, while the absolute development of green finance, particularly through bonds and loans, seems large, the green proportion of the system is growing only slowly from very low levels. To “green” the financial system, the proportion of green finance needs to expand significantly faster.

Thus, considering the overall policy activity in green finance, the application of green finance does not adequately reflect the ambition, as witnessed e.g., by the stagnating share of green finance for green loans and bonds in the overall system and the continued financing of non-green assets.

Several reasons can explain the dichotomy between signal and action.

- Lacking incentives for green over brown finance. While China’s latest green bond catalogue (2021) removed coal-fired power plants, it still includes upgrading coal-burning industrial boilers in the ‘energy efficiency’ category and thus expands lifecycles. In addition, financial incentives for brown assets have partly expanded, for example in November 2021, PBOC installed an RMB 200 billion (USD31 billion) relending program for clean coal. In May 2022, another RMB 100 billion (about USD15 billion) of relending program was issued “to support the clean and efficient use of coal”.[3] According to PBOC, the additional re-lending quota will be used to support the development and use of coal, and enhance the coal reserve capacity, with priority given to ensuring the safe production and storage of coal and ramping up the electricity coal supply for coal-fired power companies.

- Overlap of competencies between various ministries’ responsibilities and between the central and local governments may lead to overlapping standards and practices. An example is the development work of green finance led by PBOC, while MEE is responsible for climate finance and SASAC leads green finance development for state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Similarly, emission trading is overseen by both the market regulator CSRC and the MEE. Such overlaps and thus uncertainty exist in different provinces that apply different standards of green finance (e.g., Shenzhen’s green finance regulation is more advanced than that of other provinces and first-tier cities). It may lead to “supervisory duplication” or “regulatory gap”.

- Green finance as a share of the total markets remains low and an unbalanced structure exists in green financial products. Green credit and bonds are the main drivers of the current green finance market, while other instruments have a positive momentum but are relatively weakly developed, particularly for transition finance tools. The existing supporting measures are insufficient to incentivize progress for both green/low carbon and transition investment. For example, while the PBOC’s MPA measures are innovative and ambitious, the influence of banks’ greenness and the interest rates on their reserves is still marginal.

- Green financial instruments need expansion: For example, a standard for carbon-neutral bonds has not been developed yet, and it is important as China is promoting carbon sinks and ecological product value realization, etc. as key measures/investment areas to offset emissions. Transition finance – as important as it is – should have an accelerated pathway requirement to net zero.

- Lack of enabling and robust disclosure standards. Although domestic market regulators have explained the environmental disclosure requirements of various green finance instruments, there is a lack of framework and operable disclosure guidelines (e.g., for green bonds). Meanwhile, the monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems and standards are not robust enough to track the accurate use and impact of the funds. According to CBI, “any issuers often use conceptual, institutional, and general expressions when disclosing green-related information, which conveys limited substantive information and makes it difficult for investors to make objective and accurate judgments. Current information disclosure is insufficient”[4]. Climate Bonds’ data shows that the proportion of green bonds issued in the past two years with pre-release third-party assessment and certification has decreased, which means the proportion of green bonds with insufficient disclosure is on the rise. Furthermore, Chinese reporting standards might not be harmonized internationally, (e.g., with the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation).

- Lack of oversight and punishment. While MEE is publicly shaming companies for falsifying reports (e.g., as in the emission data), overall oversight capacity remains low. Similarly, violations are punished lightly, e.g., failing to provide ESG reports has fines of 100,000 (about USD15.500)[5].

- Lack of capacity and incentives within financial institutions, where capacity building is predominantly driven by top-down implementation guidance, while participation in international standards setters and related bodies (e.g., GFANZ, Equator Principles, PRI) is little. This makes ESG risk management often more of a box-ticking exercise that might include annual sustainability reports, rather than an integration of ESG risk evaluation and risk management. At the same time, financial institutions do not provide sufficient incentives for relevant staff to reward the reduction of ecological risks and improvement of green finance.

- Internationalization of Chinese green finance remains low, both regarding international investors being invested in green finance in China’s domestic market (which potentially reduces pressure on applying international standards and non-financial disclosure) and Chinese international collaboration on the financial institution level. For the latter, it is promising to see strong ambitions of greening Chinese overseas finance through GIP and BRIGC guidance, and to see China’s involvement in international standard setters (e.g., ISSB, IPSF), yet China’s financial institutions are not involved in developing and applying voluntary standards (e.g., GFANZ, Equator Principles, PRI), leaving much room for growth.

Recommendations

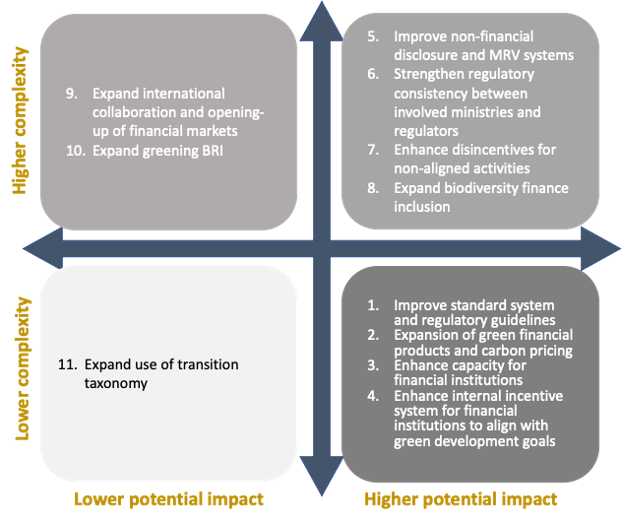

Based on the analysis of China’s green financial development as well as gaps and barriers, specific recommendations to improve green finance development in China can be developed. These recommendations can be categorized based on their potential impact on shifting finance from brown to the green and likely difficulty of implementation, as depicted in Figure below:

- Improve and strengthen green finance standards, guidelines, and supporting regulatory systems. Regulators and major financial institutions can formulate articulate, mandatory, and normative green financial policies and requirements to prevent market loopholes to reduce greenwashing. This could include

- new green finance instruments, such as transition finance instruments.

- regulations to curb activities with plausible yet hard-to-ascertain environmental benefits, such as requiring 100% use of proceeds of green bonds in the new China Green Bond Principle.

- Supervision and reduction of non-green financing activities, for example, clean coal-related investments and extensions of lifespans of existing coal plants

- Enlarge green finance in the market and expand green finance products. Policy signals and diversified green finance products can bring more players into the market and expand green finance to boost market vitality. This could include instruments, such as transition finance with stringent carbon reduction pathways and reporting requirements (like sustainability-linked securities), expansion of emission trading system to include non-compliance traders and derivatives, as well as encouraging larger green bond issuances to increase liquidity in the market.

- Enhance capacity building for financial institutions. Regulators, research institutions, NGOs, and financial institutions can expand cooperation based on existing networks such as China Banking Alliance, Green Finance Committee, Green Finance Leadership Program, and BRIGC, with new networks and partners (e.g., universities) and provide more standardized qualification systems for environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk evaluation, management, and corporate governance. International collaboration on the capacity building can play a more prominent role to share experiences both between developed countries and China and China and BRI countries. Online platforms could support systematic capacity building of smaller financial institutions, such as local commercial banks, smaller asset managers, etc.

- Enhance internal incentive and restraint polices’ for financial institutions. Regulators could incorporate more criteria for banking and other financial institutions’ green finance evaluation, e.g., based on their ability to provide consistent measurement, reporting, and validation of data. Furthermore, financial incentives could be extended to reduce green risks. Internally, financial institutions can build capacity and systems to incentivize loan officers and investment officers to better include green finance aspects (e.g., environmental risk evaluations, and environmental impact evaluations) in financing decisions. This would overcome the perception that green finance is a question of compliance and strengthen the individual motivation to expand the use of green finance concepts. This could include promotion and financial incentives for different levels of management in financial institutions.

- Advance non-financial disclosure standards and their application for financial institutions and corporations. Currently, China has a mandatory disclosure requirement for corporates but only covers conglomerates from high environmental impact sectors, which is not enough to regulate/support small and medium-sized companies in the green technology sector. FI disclosure rules are less developed, with some pilots for non-financial disclosure implemented.

Policymakers should set more stringent rules (with more severe punishment) on ESG disclosure in line with association-based standards (e.g., TCFD, TNFD) and with strong support for international standards (e.g., ISSB). This needs to be based on stronger measurement, reporting, and validation (MRV) consistent with international certification standards and procedures for third-party green assessment agencies to provide improved incentives for international investors (e.g., in green bond markets). - Strengthen consistent regulation and reduce regulatory complexity. While various Chinese regulators have built a portfolio of policies and guidances related to green finance (e.g., NDRC, MEE, PBOC, CBIRC, CSRC), regulators could strengthen cooperation amongst each other and designate a focal point for green finance with top-level authorization to ensure higher consistency among regulators and initiatives and reduce complexity for green finance. This would provide higher transparency and clearer direction for domestic and international investors. Several actions of improved cooperation have already been successful, such as the jointly issued green finance taxonomy of 2019.

- Enhance disincentives for non-green activities. Regulators should curb activities with plausible yet hard-to-ascertain environmental benefits. A foundation would be the expansion of polluting industry and activity definitions, possibly through a red finance taxonomy (like the already existing traffic light system for BRI projects that includes a “red” or discouraged activity category). Furthermore, regulators can carefully supervise and reduce non-green and not-so-green financing activities. For example, clean coal upgrades should be carefully evaluated to avoid unnecessary extension of the lifespan of existing coal-fired power plants. Next, to further ensure and elevate recent policy progress (i.e., the new guidance for outbound investment[6]), authorities can provide more stringent rules and increase accountability for those financial institutions and corporations that do not follow rules, based on introducing mandatory non-financial disclosure requirements that meet international criteria. Finally, oversight and punishment for violators should be expanded with the inclusion of grievance mechanisms in financial institutions to share responsibility for environmental violations with financial institutions.

- Expand international cooperation. China is a key contributor to global green finance development through collaboration with and leadership in international bodies (e.g., G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group, NGFS, IPSF). China can expand its cooperation for non-financial disclosure in both government-supported bodies (e.g., ISSB for ESG standards) and in voluntary standard setters (e.g., TNFD, TCFD, Equator Principles). This would require incentives or at least endorsement from the top-level government for financial institutions to actively participate in such international bodies.

Furthermore, China can further improve access to its domestic market for international financial institutions and players in various markets. As international financial institutions might have already higher capacity and requirements for environmental and social risk management and more advanced corporate governance, international practices should be invited to “spill over” into the domestic markets, e.g., for bonds, and possibly credits. - Expand biodiversity finance: China has started to include biodiversity considerations into finance through some high-level guidances (e.g., Opinions on Deepening the Reform of Ecological Protection Compensation System issued by the General Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China), through international collaboration bodies (e.g., CCICED, Green Finance Committee) and several initiatives by financial institutions. Systematic risk assessment of biodiversity-related financial risks, however, remains weak, this includes the capacity. Through improved domestic and international collaboration on biodiversity finance (e.g., TNFD), China could expand domestic capacity. Through improved disclosure regulation on biodiversity impact, for example, based on MRV systems developed for its Gross Ecosystem Product pilots, China could further expand biodiversity risk evaluations in financial institutions and financial decision-making.

- Expand greening of BRI: China’s cooperation with BRI countries can be strengthened to expand capacity and knowledge in BRI countries on China’s green finance progress and green finance stipulations in various green finance guidelines and guidances. By having BRI countries become aware and thus require higher green finance standards in line with Chinese guidances and opinions, Chinese players would overcome the non-interference requirement of China’s overseas finance, as green development requirements would be asked for by the recipient countries.

Furthermore, China could support the evaluation of accelerated phase-down of coal-fired power plants to reduce potential stranded asset risks, for example in collaboration with specific host countries that signaled interest in the early retirement of coal plants, e.g., through the ADB Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM). These countries include, for example, Pakistan, and Indonesia. Finally, non-financial disclosure of BRI projects and BRI finance can be improved in line with international standards to build trust and accelerate third-country cooperation. - Expand transition taxonomy: China has been promoting transition finance and the establishment of a transition taxonomy. This ambition is in line with G20 sustainable finance road map through the Sustainable Finance Working Group co-led by China. Transition finance is important to provide finance for hard-to-abate sectors in their transition. Yet, at this point, it is unclear whether transition finance can be successful in truly reducing emissions and nature destruction as ambitions in transition finance are due to unclear or insufficiently ambitious transition paths. Possibly it would be more relevant to provide more stringent bottom-up transition taxonomies, e.g., based on timelines of having to transition out of specific activities based on a red taxonomy, as suggested by the G20 Climate and Sustainability Working Group.

[1] 中国金融学会绿色金融专业委员会, “人民银行副行长宣昌能:进一步做好绿色金融与转型金融的有效衔接 (Xuan Changneng, Deputy Governor of the PBOC: Further improve the effective connection between green finance and transition finance),” November 2022, http://greenfinance.org.cn/displaynews.php?id=3907.

[2] 中国经济网, “易纲重磅发声 货币政策将继续从总量上发力 (Yi Gang made a big statement that monetary policy will continue to exert force from the aggregate),” June 28, 2022, http://finance.ce.cn/bank12/scroll/202206/28/t20220628_37808554.shtml.

[3] Xinhua, “China’s Central Bank Steps up Support for Clean, Efficient Coal Use”, May 2022.

[4] Long, A., Wu, V., Xu, X. & Xie, W. China’s Green Finance Policy, 2021, https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/policy_analysis_report_2021_en_final.pdf.

[5] 生态环境部, “企业环境信息依法披露管理办法-第五章 罚则 (Measures for the Administration of the Lawful Disclosure of Enterprise Environmental Information – Chapter V Penalties),” December 2021, https://www.mee.gov.cn/gzk/gz/202112/t20211210_963770.shtml.

[6] 生态环境部, 对外投资合作建设项目生态环境保护指南 (MEE: Guidelines for the Protection of the Ecological Environment of Overseas Investment Cooperation Construction Projects), January 2022, https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywdt/xwfb/202201/t20220111_966728.shtml.

Comments are closed.