Introduction

Whilst the BRI is led by Chinese industry, the private sector is cautious in its implementation of environmental protection, especially regarding biodiversity conservation.1 Chinese BRI financiers lack international best-practice safeguards, whilst the whole project may impact more than 369 000 km2 of vulnerable habitat in a 25 km buffer zone around planned BRI infrastructure. Moreover, invasive species introductions along the BRI routes are an additional threat to biodiversity. Kyrgyzstan is particularly vulnerable, since most of the country is a biodiversity hotspot; there are some protections in place but limited knowledge about the significance of the wildlife outside protected areas exists.2 The top-down green financial system of the Chinese government is yet to fully engage the private sector,3 so it will be up to the Kyrgyz Republic to ensure best practice by holding companies accountable. Considering the high levels of community activism in Kyrgyzstan, this could be a reality. However, considering Kyrgyzstan’s still ongoing ecological governance development, it will require support from international experts in the field, e.g., from international NGOs.

Kyrgyzstan: Biodiverse and at Risk

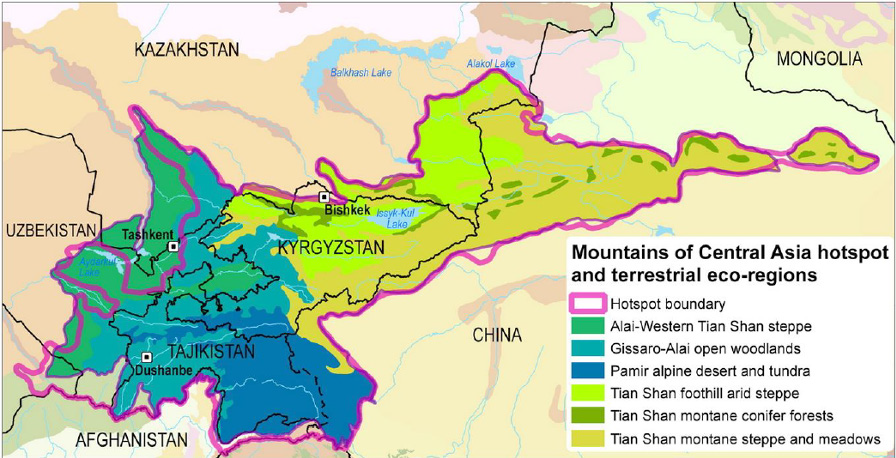

Kyrgyzstan is a mountainous, landlocked country in Central Asia. It has an average altitude of 2750 meters with 40% of the country over 3000 meters and 90% over 1500 meters. The country hosts 88 major mountain ranges, most significantly the Tian Shan, the Celestial Mountains in the North, and the Pamir Mountains in the South. Almost all of Kyrgyzstan is included in the ‘Mountains of Central Asia’ biodiversity hotspot (Figure 1), and the area is part of WWF’s Global ecoregions.

The hotspot contains many species of import, both from the perspective of conservation and agriculture. It is home to many ancestors/ wild type varieties of domestic fruits, nuts, and crops- the preservation of which should be of great value and import to global agricultural communities.4 The hotspot also contains a total of 68 globally threatened species, 19 of which are critically endangered according to the IUCN Red List.5

Considering the unique and threatened status of the country’s ecosystems, great consideration is needed to not degrade it further. As China expands its Belt and Road Initiative in Kyrgyzstan, both countries need policies to ensure not just a ‘green’ but a ‘biodiverse’ BRI in vulnerable mountainous regions. This case study will, first, investigate the biodiversity conservation progress and capacity of Kyrgyzstan. Second, it will describe the potential Chinese biodiversity protection capacity along the BRI. Finally, it will recommend areas for key focus, and highlight actions for greening BRI in Kyrgyzstan.

Biodiversity Conservation Capacity of Kyrgyzstan Governance, Institutions, and Policy

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kyrgyzstan’s environmental and ecological governance has gone through three major reforms, each increasingly emphasizing a market economy coupled by decentralization, although with complications due to poorly planned and executed system changes. Despite a well-rounded normative and legal environmental framework and membership of multiple international environmental conventions and protocols such as CITES and the CBD, the implementation of some laws is lacking in practice.6 Moreover, the governmental institutions with more power display little care for protecting the environment and biodiversity.7 For example, the previous Prime Minister, Mukhammedkalyi Abylgaziev has been charged with corruption due to signing a government decree allowing the Kumtor Gold Company CJSC to double their mining area in the vulnerable Issyk-Kul biosphere zone, despite existing bans on mining expansions in the region.

“However, considering Kyrgyzstan’s still ongoing ecological governance development, it will require support from international experts in the field, e.g., from international NGOs.”

Finance

Only around 0.5% of public expenditure in Kyrgyzstan is directed towards the environment, including biodiversity and climate change adaptation.8 The contribution of international donors is equally minor, and the role of private sector is marginal (discounting China’s potential investment through BRI).9 The Biodiversity Finance Initiative of the United Nations Development Programme has estimated that Kyrgyzstan’s biodiversity finance needs are around 30 million USD until 2023; currently, only 40% of the target as been achieved. The remaining 60% could be met by donations, public funds, and private sector contributions, a potential impactful avenue for BRI project investors. The country has set course towards creating an ‘inclusive green economy’ and has implemented it into its long-term 2040 vision.

Research, Training, and Education

Kyrgyzstan, despite its relatively small, sparse population, has 64 universities, yet none feature in the QS World University Rankings. For comparison, Kazakhstan with 125 universities, with 13 featured in the QS World Rankings and one in the Top 200. Kyrgyzstan’s educational quality can be poor with problems such as academic corruption, and many youths suffer from an educational and skills mismatch. As few of these 64 universities train conservation specialists, international organizations are highly important for providing further training both nationally and abroad.10 Further education and training in ecological and environmental protection at all stages of life is needed to further the conservation agenda.11

Management, Protection, and Use of Biological Resources

The Mountains of Central Asia hotspot includes 32 confirmed global Key Biodiversity Areas (covering 20,610 km2) and Kyrgyzstan has two Important Bird Areas both inside and outside the hotspot boundary12 (Figure 2). The percentage of protected areas has reached more than 7% of the total area of the country, although often finance and enforcement are lacking, making some protected areas by ‘name only’.13 Unfortunately, data outside of these protected areas is lacking and even though relatively good data for the areas themselves exists, limited capacity exists to fully utilise these data for conservation.14 Notably, Kyrgyzstan has no protocol in place for managing invasive species.15

Public Awareness and Action

Kyrgyzstan hosts a diverse mix of active civil society organisations, with over 200 focussing on conservation of different taxa.16 However, ecological information is not easily accessible by the public and further transparency and inclusiveness is required to increase the impact of participation by civil society.17

Key Points:

- Environmental and ecological governance are still developing, and more financing is needed.

- National conservation research capacity is dependent on international support, but civil society is very active.

- Biodiversity protections are in place but overall data limitations prevail.

China and Biodiversity

At the United Nations Summit on Biodiversity in 2020, President Xi Jinping declared China to be heading towards an ‘ecological civilization’ which ‘promotes harmonious coexistence of man and Nature’. The growing importance of biodiversity reflects well from investments: since 2017, the annual governmental biodiversity related finance is more than 260 billion yuan (~40 billion USD).18 In November 2019, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China, the Ministry of Finance of China, and the World Bank agreed on the need to promote adding biodiversity into the decision-making chains of the private sector and to mainstream its inclusion.19 However, uptake on biodiversity conservation is very low, exemplified by about 90% of environmental protection companies still being centred on pollution and waste management.20 Moreover, Chinese conservation research capacity is lagging behind its Western counterparts’, raising doubt on the future success of its biodiversity governance.

BRI: a Bumpy Road for Biodiversity

Narain et al. (2020)21 found that only a quarter of the identified BRI financiers had biodiversity impact mitigation requirements in place, of which just one organisation was Chinese, despite 90% of BRI finance originating from China. Interestingly, Chinese scientists lead on BRI research, although mere 2.8% (either in Chinese or English) is on environmental topics and majority of papers focus on Chinese routes with only 7% of Chinese papers investigating a route outside of China. The whole project has been estimated to impact more than 369 000 km2 of vulnerable habitat in a 25 km buffer zone around planned BRI infrastructure,22 with likely species invasions,23 and potential increases in forest conversion and illegal hunting and wildlife trade. In 2013, China established the Chinese Academy of Sciences Research Centre for Ecology and Environment of Central Asia in Xinjiang as part of BRI, with regional offices in all but Turkmenistan.24 Thus, some efforts for a ‘Green BRI’ have been made, but current policy is non-binding with no repercussions for breaches.

Recommendations

- Research and Education Capacity

BRI scholarships for conservation research could help build capacity both in China and in BRI partner countries.25 Equally, with China’s biodiversity conservation capacity lagging behind its Western counterparts’, China and Kyrgyzstan should partner with existing NGOs with conservation expertise to expand their capacity to monitor biodiversity and build effective governance mechanisms.

- Finance

China could do well by spreading its aspiration of an ‘ecological civilization’ through the BRI, potentially with boosting local biodiversity protection budgets. Kyrgyzstan receives a fair share of investment from Western donors, but it is still only a marginal amount26 and it could do well with additional finance to not just reach a set budget but accelerate the development of community approved conservation action.

- Debt-for-Nature

Considering China is Kyrgyzstan’s biggest bilateral creditor since 2012 and provides over a third of external debt, the Kyrgyz Republic risks reaching a state of insolvency. Since low-income countries in general are struggling to pay back loans from Chinese banks, the BRI payback schemes should consider ‘debt-for-nature’ (DFN)–reducing the debt in exchange for nature protection–which could both add extra value to loans, and position China as a world leader in biodiversity conservation funding. Cancelled or reduced debt coupled with the chance to use local currency for debt payback into conservation projects eases the overall payback burden of a debtor country. Moreover, involving a third party, either an international or local NGO, as a broker could ensure transparent and decentralized allocation of funds.27

- Protected Areas

China has the power and opportunity to initiate not just transboundary infrastructure but also well-needed transboundary conservation, especially since the Mountains of Central Asia hotspot reaches into North-West of China. Well-planned networks of protected areas coupled with wildlife corridors crossing the BRI infrastructure at vital connectivity points would ensure long-term sustainability of the projects.28

[1] Anthony Baluga, “Leveraging Private Sector Participation to Boost Environmental Protection in the People’s Republic of China,” vol. 2, 2020.

[2] The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, “Ecosystem Profile: Mountains of Central Asia Biodiversity Hotspot,” 2017.

[3] Baluga, “Leveraging Private Sector Participation to Boost Environmental Protection in the People’s Republic of China.”

[4] The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund.

[5] The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund.

[6] Temir Burzhubaev et al., “Environmental Finance Policy Abd Institutional Review in the Kyrgyz Republic,” 2019.

[7] Burzhubaev et al.

[8] Burzhubaev et al., “Environmental Finance Policy Abd Institutional Review in the Kyrgyz Republic.”

[9] The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, “Ecosystem Profile: Mountains of Central Asia Biodiversity Hotspot.”

[10] The Government of the Kyrgys Republic, “Biodiversity Conservation Priorities of the Kyrgyz Republic till 2024,” 2014, 46.

[11] Hao et al., “The Effects of Ecological Policy of Kyrgyzstan Based on Data Envelope Analysis.”

[12] The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, “Ecosystem Profile: Mountains of Central Asia Biodiversity Hotspot.”

[13] John D Farrington, “A Report on Protected Areas, Biodiversity, and Conservation in the Kyrgyzstan Tian Shan with Brief Notes on the Kyrgyzstan Pamir-Alai and the Tian Shan Mountains,” 2005.

[14] The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, “Ecosystem Profile: Mountains of Central Asia Biodiversity Hotspot.”

[15] Burzhubaev et al., “Environmental Finance Policy Abd Institutional Review in the Kyrgyz Republic.”

[16] The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund.

[17] Hao et al., “The Effects of Ecological Policy of Kyrgyzstan Based on Data Envelope Analysis.”

[18] Liu Ning, “Opening Remarks on : A New Biodiversity Finance Agenda for 2021-2030,” in Virtual Global Conference on Biodiversity Finance, 2020, 1–4.

[19] Ning.

[20] Baluga, “Leveraging Private Sector Participation to Boost Environmental Protection in the People’s Republic of China.”

[21] Narain et al., (2020)

[22] Narain et al.

[23] Liu et al., “Risks of Biological Invasion on the Belt and Road.”

[24] The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, “Ecosystem Profile: Mountains of Central Asia Biodiversity Hotspot.”

[25] Fan et al., “Build up Conservation Research Capacity in China for Biodiversity Governance.”

[26] The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, “Ecosystem Profile: Mountains of Central Asia Biodiversity Hotspot.”

[27] Conservation Finance Alliance.

[28] Ng et al., “The Scale of Biodiversity Impacts of the Belt and Road Initiative in Southeast Asia.”

Disclaimer

The report is published by the Oxford University Silk Road Society Think Tank with the support of the IIGF Green Belt and Road Initiative Center. ‘The Central Asia Way’ policy report analyses the social and environmental impacts, risks, and opportunities for regional partners and China as BRI projects continue to expand into Central Asia. This report maps out the intersection of BRI with Central Asia’s development path, and argues that an opportunity is open to explore innovative responses to the challenges of green governance.

The Oxford University Silk Road Society was established in 2017 by enterprising students keen to explore, research and discuss the countries, cultures, and peoples of the Silk Roads, both modern and historical. Through case studies or holistic reports, the think tank strive to produce rigorous, detailed analysis on the ongoing efforts to improve sustainability in the China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and make their own policy recommendations – to governments and private enterprise alike.

The full report is available on the Oxford University Silk Road Society’s website here or on our website here, with a foreword from the Founding Director of the Green BRI Center, Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG.

Currently, Minna is a student on the MSc Biodiversity, Conservation and Management degree at the University of Oxford. Previously, she worked for the British Trust for Ornithology managing a national citizen science project and processing spatial data. Minna graduated from the University of Southampton (UoS) with a BSc in Zoology with a Year in Employment. During her degree she held a public engagement position at the UoS as the University's Nature and Biodiversity Hub coordinator, completed a year in employment with the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust in Scotland, and volunteered with researchers investigating various aspects of the Tasmanian Devil facial tumour disease (DFTD) at the University of Tasmania during a study abroad semester. Coming from Estonia, she is interested in the biodiversity conservation capacity and management processes of Eastern European and Central Asian Post-Soviet countries, whilst exploring their representation in the global conservation movement. She has developed a keen interest in geoinformation science and its applications, especially for investigating the relationship of agriculture and conservation.

Comments are closed.