MDBs are increasing their involvement in sustainable infrastructure finance by scaling up climate investments and by integrating social and environmental issues into their general financing requirements as a cross-cutting issue. Based on their characteristics MDBs can play a number of important roles in greening the BRI. For the context of the BRI, this is particularly important to address four types of challenges. 1. An unfavorable institutional environment with frequent policy reversals on green technology support and an unlevel playing field towards fossil fuel projects and companies. 2. An over-emphasis of short term returns and lack of ability to accurately include physical and transition climate and environment risks in project assessments. 3. A lack of familiarity with green financing tools and ability to develop sustainable projects from projects owner in both the public and private sector. 4. The general immaturity of sustainable finance in BRI countries such as lack of sustainability data, standards, tools, in the regional and domestic financial systems. MDBs can address these issues in the BRI by using their global experience across financing and capacity solutions. Forthcoming research by IIGF will highlight MDBs other role in greening the BRI through coordination as well as policy support.

Financing and Capacity Solutions

De-risking at Project Level

For many green projects, investors and project owners perceive the risk to be too high and returns too low. Vice versa, for polluting projects investors often use historical data to perceive risk to be low and return to be high, which may lead to problems at both project level and macro level as non-performing loans accumulate and investments become stranded assets.[1] This includes both climate change related and other environmental risks that depend on the local circumstances. At the project level, MDBs can de-risk projects through a range of financing solutions as listed below:

- Technical Assistance

As the first key method of capacity building MDBs should use their know-how and technical expertise to improve stakeholders understanding of risks of both green and polluting projects. This expertise is a key characteristic of MDBs, as highlighted by the UN.[2] MDBs should utilize this characteristic at a higher degree and seek more opportunity to provide technical assistance. This can take place at difference levels of project preparation. Technical assistance can be provided to key stakeholders such as government, investors, and project holders at a general level to help them include climate and environmental risks in their risk management methodology and strategies. At the next stage, MDBs can help with technical assistance in project pipeline preparation whether it is through a project developer or designated project development facility. Once projects are identified MDBs can assist in doing feasibility studies and environmental impact assessments. Depending on the MDB and the client, these services could be provided on either market or concessional terms. As an important example of a large-scale technical assistance project, the World Bank Group’s Sustainable Finance Network gathers, analyzes and disseminates good practices of sustainable infrastructure finance across developing countries.[3]

- Risk Assessment Disclosure

A second key method of capacity building is for MDBs to be transparent in their own assessments of climate and environmental risk. In following the FSB-TCFD guidelines, MDBs should disclose the key numbers and provide an evaluation of such risks in their own portfolios.[4] This will provide a benchmark for other investors to follow, given the normative authority of MDBs in the field. This, again is effective for improving risk perception for both green and polluting projects. In addition to MDBs individually disclosing their climate and environmental risks, they should also do so through their joint reporting as they will consequently be forced to develop a common methodology that can be used as best practice for others to follow.

- Public Private Partnerships (PPPs)

In terms of financing instruments to be used for de-risking green projects, MDBs have a broad toolbox. Blended finance in a PPP model allows MDBs to use their own resources to catalyze other resources. Such catalyzation ability of MDBs is highlighted by both the UN, while MDBs estimates that $2-5 of external financing can be catalyzed for each $1 of their own financing.[5][6] As PPPs work as a continuum of ownership sharing between the public and private entity, MDBs should try to have as low as possible commitment while providing enough financing to ensure the private party’s engagement. This allows MDBs to maximize their private capital catalyzation ability. An example of an MDB led PPP initiative with a strong climate component is the EIB’s Med5P, working with public authorities on preparation, procurement and implementation of PPP infrastructure projects.[7]

- Concessional and Non-Concessional loans

As the primary vehicle for MDBs financial operations, direct loans are a key contributions MDBs can make to greening the BRI. The key advantages of MDB loans are firstly that they are longer term and stable. While the average length of corporate loans in China and many BRI countries is merely 5 years, MDB loans often run for 20-25. This lowers the transaction costs and uncertainty associated with refinancing a project a number of times over its lifespan. A second advantage is that MDB loans may be concessional. This lowers the cost of capital, making a project bankable irrespective of changing the risk perception. Ultimately, the amount of green loans depends on MDBs strategy for capital allocation, highlighting the importance of MDB members setting hard quantitative proportional targets for climate and green financing. Concessional terms are particularly relevant in sustainable infrastructure development where risk is perceived as higher and consequently used to provide demonstration effects.[8]

- Guarantees and Insurance

To lower the climate and environmental risk carried by investors, MDBs can provide a number of different guarantees and insurances. By covering a government or government entity’s potential failure to meet financial obligations to a private or public project, MDBs’ guarantees have helped attract direct private sector investment.[9] As risk of often perceived to be higher for green projects, increasing MDBs efforts through guarantees has a particularly important role to play for the green sector. Sector specific risks include risk from an unstable political support in terms of reversal of subsidies or power purchase agreements for renewable energy. Additionally, as the actual risk is often lower than the perceived risk, MDBs are consequently have a smaller potential liability than for non-green projects. Such guarantees could also be privately provided, by banks or specialized institutions, or governments, but for BRI countries with high risks and unsophisticated financial markets, MDBs’ mandate is particularly suitable.[10] A successful case of insurance is the Global Index Insurance Facility by the IFC, which facilitates access to finance for farmers, entrepreneurs, and microfinance institutions through the provisions of catastrophic risk transfer solutions and index-based insurance in developing countries.[11]

- Risk Sharing Facilities

Such a facility works as a loss-sharing agreement between an MDB and a holder of assets in which the MDB reimburses the asset holder for a portion of the losses incurred on a portfolio of eligible assets. For example, the facility could allow a client to sell a portion of the risk associated with a pool of assets. For greening the BRI, MDBs could use such a facility together with local banks to increase their commitments to issuing green loans. Over the last years, risk sharing facilities have become increasingly used by MDBs such as the IFC, EBRD, EIB, and AfDB, replacing other tools for address sub-investment grade risk clients.[12] This is particularly feasible for MDBs with majority voting power of developing countries, as these are statistically less risk averse.[13] The EIB’s Private Finance for Energy Efficiency scheme provides a successful case study of such a risk sharing facility.[14]

- Hedging, Derivatives & Swaps

MDBs’ stand-alone products for risk management help investors manage their financial risks. Using standard risk management techniques, these products can transform the risk characteristics of a borrower’s obligations without changing the terms negotiated in the loan agreements. As an example, the World Bank Group has provided catastrophe swaps in the Caribbean region, exchanging a fixed payment for a part of the difference between insurance premiums and the losses caused by insurance claims.[15] This practice should be increasingly applied by MDBs in the BRI since such products are currently lacking and as financial costs from extreme weather events are increasing. Often the cost trickles down to the central government, resulting in financial stress on public budgets. MDBs can contribute to avoiding such circumstances.

Project Pipeline and Project Development Costs

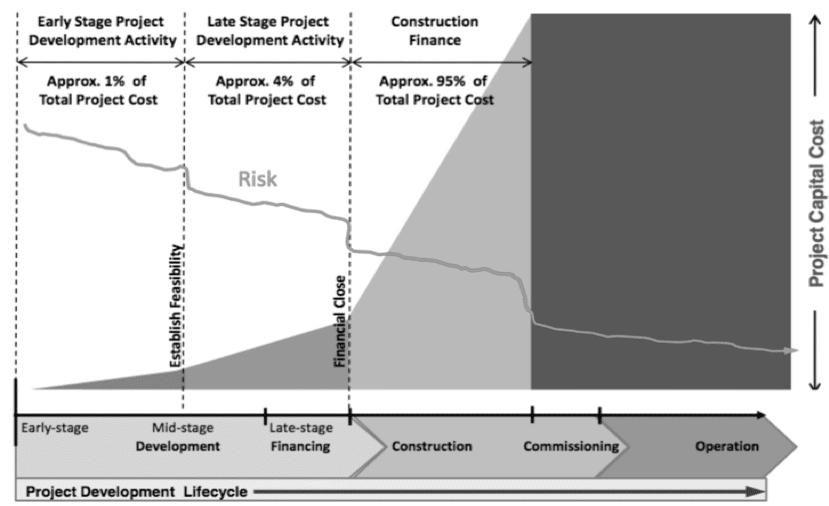

A key issue for infrastructure projects in general and in particular for green infrastructure is the lack of a pipeline of potential bankable projects as well as high project development costs. As risk is particularly high at the early project stage, MDBs can play an important role in carrying this risk, while leaving the later stage to commercial investors. The project risk profile over time is visualized in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Risk and capital costs during the project development lifecycle

Source: UNEP & Aequero (2011). Catalyzing Early Stage Financing. Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP

Transaction costs for preparing greener projects is also higher than conventional projects as green projects often carry higher technological risks from using less mature and proven technologies. While the short-termism of many investors makes them less interested in infrastructure projects, long term institutional investors such as sovereign wealth funds, pension funds, and insurance companies are often discouraged by the higher risks from green projects and from less stable political circumstance in many BRI countries. MDBs’ involvement in the early stages of project preparation can help to make projects an investible asset class for short-term investors and lower the risk to attract long-term investors. A systematic approach by MDBs individually and in cooperation is required develop a sufficiently large pipeline. This change is in contrast to today’s situation where MDBs still principally deliver tailored projects that are hard to scale up because they are demanding and time-consuming to prepare. However, MDBs are starting to collaborate more to build such systems.[16] MDBs can contribute to project pipeline and development through a number of financing solutions as listed below:

- Feasibility Studies

A first method for MDBs to contribute to project pipeline development is to use their expertise to do feasibility studies. This can be done either through a grant, concessional, or market based terms, depending on difficulty of finding alternative actors to carry out feasibility studies. With sustainability embedded in their mandates and historical experience with mature and new green technologies, MDBs experience with evaluating projects for their own financing can also be used to evaluate projects for other investors to finance. Such a tool can have a particularly strong catalyzing effect as the MDB commits only a small proportion, about 1%, of total project financing. A creative business model for MDBs to finance feasibility studies is to only charge for the studies that successfully reaches financial closure, charging a premium for the successful projects to cover the losses of the unsuccessful projects. An example is the World Bank Group International Development Association’s $18mn feasibility studies fund under the Afghani Ministry of Finance.[17]

- Hedging, Derivatives & Swaps

In addition to providing feasibility studies that allows investors to more accurately estimate the project risk, MDBs can carry some part of early stage financing themselves. With much interest in green BRI projects but a limited number of bankable projects for international investors to finance, MDBs early stage financing can bring such projects to the international market. This can often be done in cooperation with local and national development banks that have similar mandates as MDBs. This will often be in conjunction to having conducted the feasibility study first, while not being able to adequately catalyze alternative sources with the project’s current risk profile. By committing financing past financial closure, MDBs can drastically reduce the risk to be carried by other parties. MDBs can subsequently sell off the asset to free up the capital to be used for new projects, maximizing private capital catalyzing rates. Because of the low liquidity that currently characterizes sustainable infrastructure assets, the sale of the assets is not currently common. However, with sustainable infrastructure becoming an international asset class driven by institutional investors, this modality is likely to expand in the future.[18]

- Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs)

A concrete method for facilitating access to project finance is the creation of SPVs. An SPV is a legal entity created for a specific purpose which for raising capital can be used as a funding structure, by which all investors are pooled together into a single entity. With the higher risk of green infrastructure projects in BRI countries, an SPV setup can work as a risk-sharing mechanism that isolates project risk from the parent company while allowing other investors to take a part of the risk. MDBs can contribute both with technical assistance for national and local governments to establish SPVs and also by carrying a stake in the SPV themselves. Combined with green standardization of BRI infrastructure as an asset class, SPVs can be used to attract asset managers and infrastructure funds who want to increase their exposure in this field.[19] A large-scale example of successful support of an MDB to a green infrastructure SPVs can be seen in AfDB’s involvement in the Lake Turkana Wind Project.[20]

- Project Preparation Facilities (PPFs)

Combining different parts of the above three methods, PPFs increase the speed and reduces the transaction costs for developing infrastructure. In immature infrastructure markets of many BRI countries which have weak links to global financial markets, PPFs can have a particularly critical role to play. MDBs can contribute to PPFs as initiator and facilitator as well as with technical and financial contributions. In practice, PPFs bring together all stakeholders involved in an infrastructure project and uses a more or less standardized method for project development a selection. This is what increases pace and reduces transaction costs. With a very limited number of existing facilities for green BRI projects, this is a gap that MDBs can contribute to filling. With their developmental mandates, MDBs are the logical party to bring together all stakeholders on an objective platform. The current status of PPFs is that in response to the difficulties many countries face in developing bankable infrastructure projects, a large number of PPFs have been established in recent years and investment in existing institutions has also increased.[21] Globally, there are now over 60 such facilities, including the World Bank Group’s Global Infrastructure Facility, the EBRD’s IPPF, the ADB’s Asia-Pacific PPF and Green Finance Catalyzing Facility, the NEPAD-IPPF of the AfDB, as well as country-specific facilities. Given the immense infrastructure needs of BRI countries, there remains plenty of room to scale up and replicate such facilities. The ADB case simultaneously provides an interesting example of an MDB providing a platform for project development where experts can provide input for improving project structuring.[22]

[1] Financial Stability Board – Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (2017). Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Basel, Switzerland: FSB

[2] Addis Ababa Action Agenda (2015). Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: United Nations

[3] International Financial Corporation (2018). Sustainable Banking Network. Retrieved from: http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/sustainability-at-ifc/company-resources/sustainable-finance/sbn

[4] Financial Stability Board – Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (2017). Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Basel, Switzerland: FSB

[5] Addis Ababa Action Agenda (2015). Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: United Nations

[6]African Development Bank et al. (2015). From Billions to Trillions: MDB Contributions to Financing for Development

[7] European Investment Bank (2019). MED 5P. Available from: https://www.eib.org/en/projects/regions/med/med5p/index.htm

[8] Development Finance Institutions (2017). DFI Working Group on Blended Concessional Finance for Private Sector Projects.

[9] African Development Bank et al. (2017b). Catalogue of the MDBs and the IMF Financing Solutions

[10] Asian Development Bank (2017). Meeting Asia’s Infrastructure Needs. Manila, Philippines: ADB

[11] International Financial Corporation (2017). Global Index Insurance Facility. Available from: http://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/industry_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/financial+institutions/priorities/access_essential+financial+services/global+index+insurance+facility.

[12] African Development Bank et al. (2017b). Catalogue of the MDBs and the IMF Financing Solutions

[13] Brookings Institution (2018). Time to reform the multilateral development bank system. Retrieved from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2018/02/20/time-to-reform-the-multilateral-development-bank-system/

[14] European Investment Bank (2019b). Private Finance for Energy Efficiency. Available from: https://www.eib.org/en/products/blending/pf4ee/index.htm

[15] World Bank Group (2008). Caribbean: Participants Renew Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility for 2008 Hurricane Season. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2008/06/09/caribbean-participants-renew-catastrophe-risk-insurance-facility-for-2008-hurricane-season

[16] Brookings Institution (2018). Time to reform the multilateral development bank system. Retrieved from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2018/02/20/time-to-reform-the-multilateral-development-bank-system/

[17] World Bank Group (2018). ARTF – Feasibility Studies Facility. Available from: http://projects.worldbank.org/P091259/artf-feasibility-studies-facility?lang=en

[18] Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (2017). Global Sustainable Investment Review 2014-2016.

[19] UK-China Green Finance Task Force (2017). Interim Report: Turning Green Momentum into Action. Beijing, China: UK-China GFTF

[20] African Development Bank (2019). Lake Turkana Wind Power Project: The largest wind farm project in Africa. Available from: https://www.afdb.org/en/projects-and-operations/selected-projects/lake-turkana-wind-power-project-the-largest-wind-farm-project-in-africa-143/

[21] Hoare, A. Hong, L. Hein, J (2018). The Role of Investors in Promoting Sustainable Infrastructure Under the Belt and Road Initiative. Chatham House Research Paper May 2018.

[22] Asian Development Bank (2017b). Catalyzing Green Finance: A Concept for Leveraging Blended Finance for Green Development. Manila, Philippines: ADB.

Mathias Lund Larsen is non-resident research fellow at the Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University. He is also a dual PhD Fellow at Copenhagen Business School and the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Sino-Danish Center for Education and Research). His research is focused on the political economy of green finance in China from theory to practice, intention to impact, and domestic to overseas.

He has spent more than a decade working on the intersection between China, sustainability, and finance, and speaks fluent Chinese. He has previously held positions in the UN in New York, Nairobi, Bangkok, and Beijing and holds two double Masters degrees in and around political economy from Copenhagen Business School, Rotterdam School of Management, Sciences Po Paris, and Peking University.

Comments are closed.