While green bonds remain the most mature instruments, a wide range of innovative financial solutions are rapidly developing.

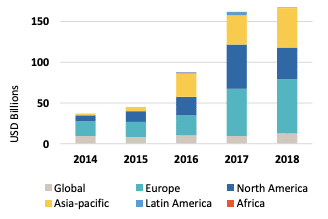

Issuing green bonds, i.e. bonds whose proceeds are earmarked for funding climate and environmental-friendly projects, is an effective and increasingly popular way to achieve this end. In just over a decade, annual green bond issuance grew over 100 times in terms of total value: from USD 1.5 billion in 2007, to USD 167 billion in 2018. Increasingly, bond issuers in Asia are picking up the practice: whereas China had still not issued a single green bond in 2015, in 2016 it accounted for 40.9% of global green bond issuance (followed by 24.6 % in 2017 and 23.0% in 2018 ).[1] Furthermore, India financed part of its 2022 renewable energy targets through the issuance of green bonds by public institutions and corporations (Source).[2] Additionally, whereas ASEAN’s green bond issuance was USD 2.3 billion in 2017, its green bond issuance cumulatively stood at over USD 5 billion in 2018, of which 39% was issued in Indonesia.[3] The largest underwriter of green bonds globally, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, expects Asia’s total green bond issuance to be around USD 600 billion in the upcoming five years (Source),[4] while the former head of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), Christina Figures, aims for USD 1 trillion globally by 2020 (Source).[5] Hence, though green bond issuance may have started in Europe, a vastly growing number of public and private organizations in Asia are embracing this instrument for their sustainable development.

Essentially, the key motivations for issuers to issue with a green label is that green bonds can help attract new investors while highlighting the sustainability ambitions of the issuer. Today, a growing amount of research also shows that a green premium exists for most markets, issuers, locations, and currencies.[6] This premium is the result of the existence of a greater demand for green bonds than total green bond issuance at the moment. This trend is clearest in secondary markets. Additional benefits include increased visibility and attention to the issuer’s sustainability credentials, as well as the issuer being considered an early adopter, giving demonstration effects to other organizations.

Some commentators disagree with the fundamental necessity of labelled financial instruments, whether they be green, sustainable, social, or other. Their main argument is that rather than creating labelled financial instruments as a niche market, the best way to finance sustainable projects is to make organizations as a whole more sustainable so that any bond issued will automatically be green. This would have to go hand-in-hand with increased sustainability disclosure requirements and third-party verification, to prove the sustainability characteristics to investors. Whereas in the long-term this might be a satisfactory solution, the development of sustainable finance instruments is critical in the short- and medium-term to finance sustainable development in the coming years.

Providing a practical guide for issuing green bonds, the International Capital Markets Association (ICMA) launched the Green Bond Principles (GBPs) in 2014. While being only abstract principles briefly explained in a five-page document, the GBPs are a common reference point, used by most regulators and issuers across the world. The GBPs covers the use of proceeds, project selection and evaluation, management of proceeds, and reporting.[7] These principles were launched once the green bond market had reached 10 billion USD, and hence became big enough for corporations to also issue green bonds which enhaned fears of ‘green washing’.

A growing toolbox of sustainable finance instruments

The green bond, however, is no longer the only debt-finance instrument used to raise private funds for sustainable development in Asia. In addition to the sustainable-debt market growing rapidly in size (by 26% between 2017 and 2018, reaching 247 billion USD worth of issuance of sustainable debt products),[8] this market has also diversified over the past four years, with the introduction of four additional instruments: sustainability bonds, social bonds, green loans, and sustainability-linked loans (or sustainability-improvement loans, or ESG-linked loans). The growth of the market in absolute terms, and the diversification of sustainable finance instruments, as shown in figure 1 below, should be seen as a testament to the vast increase in market demand for sustainable finance products. As the majority of these instruments could be employed as a means to achieve financing for sustainable projects that Asia requires, their characteristics, market size, and the development stage of corresponding regulatory frameworks should be considered before concluding that green bonds are the most mature, and therefore the most appropriate financing tool to achieve sustainable development in Asia.

Sustainability Bonds

As an alternative to green bonds, the first sustainability bond was issued in 2014 by Unilever (GBP 250 million). The International Capital Market Association (ICMA) defines sustainability bonds as bonds whose proceeds are applied exclusively to finance or re-finance a combination of green and social projects,[9] i.e. projects with clear environmental and socio-economic benefits.[10] For this reason, the Sustainability Bond Guidelines (SBG) published by the ICMA in June 2018 have the same four core elements as ICMA GBPs.[11] Such standardization of practices between sustainable finance instruments facilitates the development of new instruments and reduces the transaction costs for issuers who first issued green and then sustainable, or vice versa. In 2018, total sustainable bond issuance was roughly USD 12 billion. This was the first year that issuance surpassed USD 10 billion.[12] In addition, in 2018, the European Investment Bank (EIB) issued a EUR 500 million sustainability awareness bond, aiming to expand the benefits of impact reporting and transparency beyond climate change and using the proceeds to fund high-impact water projects.[13] Considering the accompanying demonstration effect and organizational scale, increasing issuance by such multilateral development banks (MDBs) could expand market issuances by others in the future.

Social Bonds

The second sustainable-debt financing innovation came about in 2015 with the issuance of the first social bond. The International Capital Market Association (ICMA) defines social bonds as bonds whose proceeds are used exclusively to finance or re-finance social projects, i.e. projects with clear socio-economic benefits.[14] The principal attempt to establish norms for social bond issuance came about with the ICMA’s release of the Social Bond Principles (SBPs) in June 2017. One of the largest social bonds issued to date is the EUR 500 million Korean Housing Finance Corporation Social Covered Bond, which, which was verified by Sustainalytics to be in line with the SBPs. In 2018, social bond issuance totaled at roughly USD 11 billion as social bond issuance for the first time exceeded USD 10 billion per annum.[15]

Sustainability in the Loan Market

More recently, labelled sustainable debt-financing products that focus on raising funds in a sustainable fashion outside of capital markets have been invented. This development was mostly a consequence of insufficient green bond issuance to meet the demand of sustainable investors.[16] Instead, green and sustainability-linked loan structures have been invented in order to accomplish sustainability aims.[17] While the bonds listed above are mostly relevant to larger organizations with a size and credit rating sufficient to be active in debt capital markets, different forms of sustainable loans can also serve small- and medium-sized enterprises, special purpose vehicles, individuals, and other smaller entities. There is, however, an attribute of sustainability loans that can compromise their impact. Essentially, unlike bonds green loans, sustainability loans are private, and for this reason, the level of reporting in the public domain is less rigorous than for bonds.[18] While it is possible for the creditor and debtor to disclose the terms of the sustainability-linked loans, this is not required. Green bonds on the other hand are almost always exclusively publicly listed with details on external verification.

Green Loans

The labelled green loan market began in 2016 with Lloyds Bank’s USD 1.27 billion earmarked loans for greener real estate companies in the United Kingdom. Yet, outside the official concept of a green loan, banks have always been giving loans to projects with environmental benefits. For example, China has been measuring its green loan proportion since 2007, which has, at present, exceeded 10%. The sustainability-character of green loans is based on the fact that their proceeds are used exclusively for environmentally beneficial activities. Therefore, green loans follow a similar framework as the green bond. In fact, the Loan Market Association (LMA) and the Asia Pacific Loan Market Association (APLMA) issued the Green Loan Principles (GLPs) that, like the Sustainability Bond Guidelines, are based on the GBPs, and share the four aspects of the GBPs. Frasers Property imported the syndicated green loan structure to Asia for the first time in 2018, helping to increase the firm’s environmental, social, and governance (ESG) rating, and thereby improving its odds of issuing a green bond in the future. Despite their rapid growth, green loans constituted the smallest share of the sustainable debt market in 2018, as total green lending remained around USD 6 billion.

Sustainability-Linked Loans

The predominant sustainable loan structure is the sustainability-linked loan (or sustainability improvement loan, or ESG-linked loans). In a sustainability-linked loan (SLL), also known as sustainability improvement loan or ESG-linked loans, the terms of the loan is linked to how borrowers score on predetermined sustainability factors such as environmental, social, governance (ESG) rating or ESG-related indicators. The ESG rating for a company is typically determined by an independent ESG-rating party such as Sustainalytics, The ESG concept is chosen as a framework given its long history of being applied for research on correlation between ESG variables and financial performance. Based on the ESG concept, the variables chosen for this type of loan differs by the nature of the borrower, as tailored to a specific industry. If the borrower achieves its ESG-rating targets over a specified time period agreed upon by the lender and the borrower in advance, then the latter receives an improvement on the loan terms agreed upon in advance, which in most cases is a reduction in interest rate. In some cases, the reverse is also true: If the ESG-rating of the borrower decreases over the duration of the loan, the interest rate increases.

Hence, unlike in the case of green, sustainability and social bond issuance, or the green loan, where the primary quality is the appropriate expenditure of its proceeds on specific green, sustainable or social projects, sustainability-linked loans are uniquely linked to a borrower organization’s ESG-rating overall. In this sense, such loans can be a first step towards increasing sustainability performance of organizations with a limited part of their activities belonging to what is commonly labelled as ‘sustainable’.

However, the sustainability linked loan’s focus on overall ESG-rating is also the instrument’s weakness. Roumpis and Cripps of Environmental Finance warn that although lenders are often happy to announce that they lend out sustainability improvement loans, the criteria on which the interest rate actually hinges can remain vague. – especially in comparison to the way in which all other sustainable finance instruments have an ESG-impact: on the basis of appropriate use of proceeds on a predetermined set of eligible activities. For this reason, for the sustainability linked loans to become a more effective low-threshold entrance to sustainable finance, the criteria of how ESG-improvement is measured should be formalized and disclosed publicly.

The concept of a sustainability-improvement loan was pioneered by ING and Sustainalytics. The pioneering loan of EUR 1 billion to Philips in April 2017 was structured by ING and supported by a consortium of 15 other banks. Even though the practice of giving out sustainability improvement loans has only begun recently, this sustainable debt financing instrument was the story of 2018, as yearly sustainability-linked lending increased by 677% between 2017 and 2018 reaching an impressive USD 36 billion.[19] While the above cases were carried out without a set of guidelines, in March 2019 the LMA issued the Sustainability Linked Loan Principles to provide guidance and a common framework for creditors, debtors, and verifiers.[20]

Comparing Sustainable Finance Instruments

While more sustainable debt financing products are entering the market, and as additional sustainable finance instruments grow their market share by the year making it likely that the green bond’s market share will further decrease in the future, the green bond remains the most mature sustainable financing tool in 2018. This is the case for three reasons: Green bonds dominated the sustainable debt market even in 2018, the regulatory environment for green bonds is the most developed compared to other sustainable finance instruments, and the sustainable-effects of green bonds are easier to verify as those of sustainable debt-financing products in the loan market. In fact, whereas the entire global market grew by 26% to a total of USD 247 billion in sustainability-themed debt instruments raised during the year, green bond issuance still made up over 73% of the market (USD 182.2 billion in yearly issuance).[21] In addition, green bond issuance goes back to 2007, whereas the first sustainability bond was only issued in 2014, the first social bond in 2015, the first green loan in 2016, and sustainability-linked loan in 2017. As a consequence, regulatory initiatives for green bonds such as guidelines and taxonomies are at advanced stages of development, especially in the European Union (EU) and China, and to a lesser extent in Japan, India, and ASEAN. Finally, because the loan market is private, in general the correct application of the green loan and the sustainability-improvement loan is more difficult to verify. The sustainability linked loan has the additional weakness – that the ESG-criteria on which the sustainability improvement loans interest rate is dependent remain vaguer than the standard way in which to ensure environmental benefits: the use of proceeds in eligible categories. Hence, in spite of the rapid growth of all sustainable finance instruments, green bonds are the most mature and suitable debt financing tool that Asian governments, institutions, and corporations can employ to achieve the sustainable investment that Asia requires.[22]

Figure 1. Comparison of sustainable finance instruments

| Financial Instrument | Year of first application | Sustainability impact via | Use of Proceeds | ICMA/LMA Guidelines | Total Issuance 2018 (USD)[23] | Market Share (in 2018) | Growth (2017 to 2018) | |

| Green Bond | 2007 | Use of Proceeds | Green | Green Bond Principles (GBP) | 2014 | 182.2 billion | 73.8% | 5% |

| Sustainability Bond | 2014 | Use of Proceeds | Green and Social | Sustainability Bond Guidelines (SBG) | 2017 | 12 billion | 4.8% | 14% |

| Social Bond | 2015 | Use of Proceeds | Social | Social Bond Principles (SBP) | 2017 | 11 billion | 4.4% | 29% |

| Green Loan | 2016 | Use of Proceeds | Green | Green Loan Principles (GLP) | 2018 | 6 billion | 2.3% | |

| Sustainability-Linked Loan | 2017 | Sustainability performance | General Corporate Purposes* | Sustainability Linked Loan Principles (SLLP) | 2019 | 36.4 billion | 14.7% | 677% |

| Total | 247 billion | 26% |

Recommendations:

- Learning the lessons from green bonds: As reaching the sustainable development goals requires financing from all tools in the financial system, it is important that all tools are rapidly scaled up. As green bonds is the most mature in the toolbox, developing similar instruments can learn the lessons of green bonds. That includes the standards of project eligibility clarify what use of proceeds can be used towards, verification requirements such as for external and second opinions, as well as information disclosure such as for issuers to be posted on exchanges.

- Ensuring international coordination and harmonization: As sustainable finance is maturing in China, Asia, and the rest of the world, developing sustainable finance tools needs to be harmonized to fit with the global nature of capital markets. This allows for Asian companies to access the sustainability conscious investors in particularly in Europe such as pension funds and insurance companies. Initiatives towards such harmonization includes that of the China Green Finance Committee and the European Investment Bank on developing a common language for green finance.

[1] 中央财经大学绿色金融国际研究院 (2018) 中国绿色债券发展报告. (International Institute of Green Finance (2018). China Green Bond Market Development Report 2018. Beijing, China: IIGF.)

[2] Climate Bonds Initiative (2018). India Ranks 8th in World for Climate Aligned Bond Issuance. Available from: https://www.climatebonds.net/resources/press-releases/2018/10/climate-bonds-state-market-report-points-huge-india-green-growth

[3] Climate Bonds Initiative (2018). ASEAN Green Finance: State of the Market 2018. London, UK: CB

[4] Investment and Pensions Europe (2018). Bank analysts estimate $600bn of green bonds from Asia by 2023. Available from: https://www.ipe.com/news/asset-allocation/bank-analysts-estimate-600bn-of-green-bonds-from-asia-by-2023/www.ipe.com/news/asset-allocation/bank-analysts-estimate-600bn-of-green-bonds-from-asia-by-2023/10024890.fullarticle

[5] Figueres, C. (2018). Ex-UN climate chief calls for green bonds to hit $1 trillion by 2020. Available from: https://www.climatechangenews.com/2018/03/21/ex-un-climate-chief-calls-green-bonds-hit-1-trillion-2020/

[6]Zerbib, O. D. (2019). The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: Evidence from green bonds. Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 98 (p. 39-60)

[7] International Capital Market Association (2018). Green Bond Principles. Zurich, Switzerland: ICMA

[8] Bloomberg (2019) Sustainable Debt Market Sees Record Activity in 2018. Available from: https://about.bnef.com/blog/sustainable-debt-market-sees-record-activity-2018/

[9] International Capital Market Association (2018) Sustainability Bond Guidelines (SBGs). Zurich, Switzerland: ICMA

[10] Nasdaq (2019). Sustainable Bonds. Available from: https://business.nasdaq.com/list/listing-options/European-Markets/nordic-fixed-income/sustainable-bonds

[11] International Capital Market Association (2018) Sustainability Bond Guidelines (SBGs). Zurich, Switzerland: ICMA

[12] Bloomberg (2019) Sustainable Debt Market Sees Record Activity in 2018. Available from: https://about.bnef.com/blog/sustainable-debt-market-sees-record-activity-2018/

[13] European Investment Bank (2018). EIB Issues First Sustainability Awareness Bond. Available from: https://www.eib.org/en/infocentre/press/releases/all/2018/2018-223-eib-issues-first-sustainability-awareness-bond.htm

[14] International Capital Market Association (2018). Social Bond Principles (SBP). Zurich, Switzerland: ICMA

[15] Bloomberg (2019) Sustainable Debt Market Sees Record Activity in 2018. Available from: https://about.bnef.com/blog/sustainable-debt-market-sees-record-activity-2018/

[16] ‘”As there are not enough green bonds to cater for demand, we are seeing green investors and larger investors that increasingly allocate part of their mandate to green finance become attracted to the green loans market” – Leonie Schreve, ING, Global Head Sustainable Finance, in Environmental Finance (2018). The green and sustainability loan market: ready for take-off. Available from: https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/analysis/the-green-and-sustainability-loan-market-ready-for-take-off.html

[17] It is important to note that while unlabeled loans are often used to finance sustainable activities, it is the labelling that constitutes an innovation, and consequently creates a new sustainable finance instrument.

[18] ’However, there are some practical differences between the two sets of voluntary principles. For example, because loans are private, the level of reporting in the public domain may be slightly less than for bonds, Dawson explains.’ Clare Dawson, CEO of the LMA in Roumpis and Cripps, in in Environmental Finance (2018). The green and sustainability loan market: ready for take-off. Available from: https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/analysis/the-green-and-sustainability-loan-market-ready-for-take-off.html

[19] Bloomberg (2019) Sustainable Debt Market Sees Record Activity in 2018. Available from: https://about.bnef.com/blog/sustainable-debt-market-sees-record-activity-2018/

[20] Loan Market Association (2018). Sustainability Linked Loan Principles (SLLP). London, UK: LMA

[21] Bloomberg (2019) Sustainable Debt Market Sees Record Activity in 2018. Available from: https://about.bnef.com/blog/sustainable-debt-market-sees-record-activity-2018/

[22] While this is the case today, the entire toolbox of sustainable finance instruments should continue to grow as a whole, especially the use of in order bonds to access global capital should go hand in hand with loans to use the credit-driven financial systems of Asian countries.

[23] Bloomberg (2019) Sustainable Debt Market Sees Record Activity in 2018. Available from: https://about.bnef.com/blog/sustainable-debt-market-sees-record-activity-2018/

Mathias Lund Larsen is non-resident research fellow at the Green Finance & Development Center, FISF Fudan University. He is also a dual PhD Fellow at Copenhagen Business School and the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Sino-Danish Center for Education and Research). His research is focused on the political economy of green finance in China from theory to practice, intention to impact, and domestic to overseas.

He has spent more than a decade working on the intersection between China, sustainability, and finance, and speaks fluent Chinese. He has previously held positions in the UN in New York, Nairobi, Bangkok, and Beijing and holds two double Masters degrees in and around political economy from Copenhagen Business School, Rotterdam School of Management, Sciences Po Paris, and Peking University.

Comments are closed.