In September 2021, a new project finance handbook was launched with funding by the British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO). The handbook was developed over several months with the goal to understand the gap and bridge the gap between Chinese style and international project financing approaches.

The handbook is based on in-depth research including over 15 interviews with leading Chinese and international investors and project sponsors with public and private ownership, including China’s leading overseas insurer Sinosure, China Import-Export Bank (China EXIM Bank), Bank of China, China Civil Engineering Construction Company (CCECC), China Railway International Corporation (CRIC), TrinaSolar.

Highlights

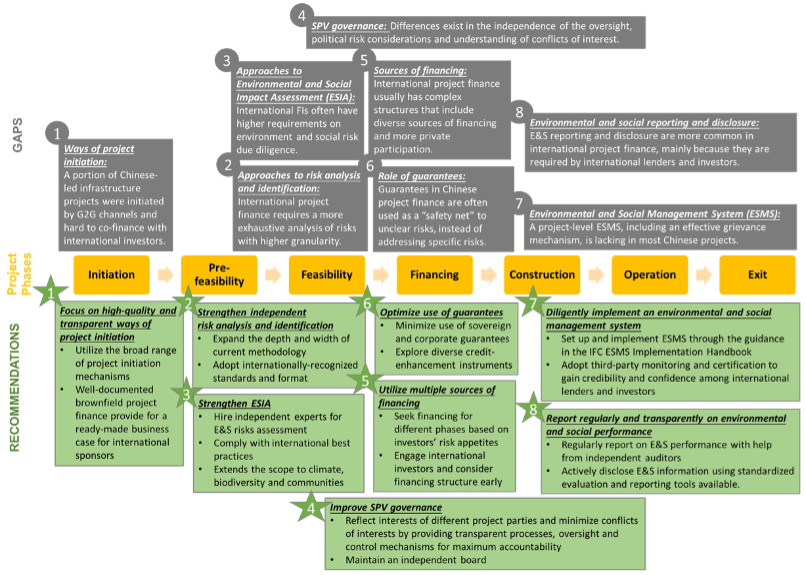

The handbook highlights 8 recommendations based on 8 identified gaps (see Figure 1 below). The identified gapsand differences between Chinese-style and international project financing are:

- Ways of project initiation: A small number of Chinese-led infrastructure projects were initiated by G2G channels and thus are hard to co-finance with international investors;

- Approaches to risk analysis and identification: International project finance requires a more exhaustive analysis of risks with higher granularity.

- Approaches to Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA): International FIs often have higher requirements on environment and social risk due diligence.

- SPV governance: Differences exist in the independence of the oversight, political risk considerations, and understanding of conflicts of interest.

- Sources of financing: International project finance usually has complex structures that include diverse sources of financing and more private participation.

- Role of guarantees: Guarantees in Chinese project finance are often used as a “safety net” for general unclear risks instead of addressing specific risks.

- Environmental and Social Management System (ESMS): A project-level ESMS, including an effective grievance mechanism, is lacking in most Chinese projects.

- Environmental and social reporting and disclosure: E&S reporting and disclosure are more common in international project finance, mainly because they are required by international lenders and investors.

Based on the gaps, 8 recommendations were developed

Recommendation 1: Focus on high-quality and transparent project initiation, utilising a broad range of project initiation mechanisms, such as project initiation facilities or early-stage project developers;

Recommendation 2: Strengthen independent risk analysis and risk identification early in the project development stage to better allocate risks to relevant partners;

Recommendation 3: Strengthen environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) to not only obtain a local ESIA license, but to clearly reduce the environmental and social risks of projects;

Recommendation 4: Improve governance of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV) to reflect the different interests of the project stakeholders and minimise conflicts of interests, by providing transparent processes, oversight, and control mechanisms;

Recommendation 5: Utilise multiple sources of financing in different project phases, from early-stage financing through loans, export credits and equity to later stage financing through, e.g., project bonds or institutional debt funds;

Recommendation 6: Minimise use of sovereign and corporate guarantees, explore diverse credit enhancement instruments;

Recommendation 7: Diligently set up and implement an environmental and social management system including an early warning system and a grievance mechanism in order to be able to quickly react to risks and events in a consistent and strategic manner;

Recommendation 8: Report regularly and transparently on environmental and social performance, ideally prepared by independent consultants and auditors.

The handbook further introduces three financing mechanism that allow for accelerated project finance, particularly for sustainable infrastructure projects:

- Sustainability linked loans to incentivize ESG improvement

- Infrastructure securitization platform to mobilize private capital

- Blended finance co-lending platforms for credit enhancement.

The handbook is available for download here.

Global Infrastructure Investment Gap

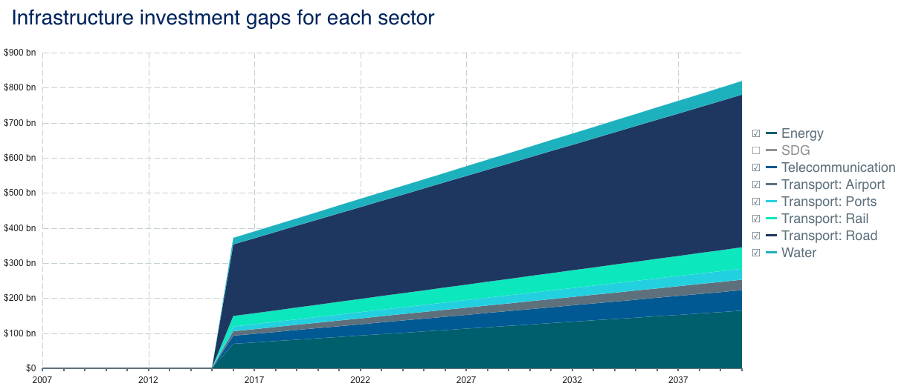

Global infrastructure investments continue to trail behind global infrastructure finances needs: According to the Global Infrastructure Hub (GI Hub) calculations, the world faces a USD 15 trillion investment gap in infrastructure by 2040[1]. In different infrastructure sectors, the estimates range from an infrastructure investment gap of about USD 125 billion per year for energy to USD 329 billion in road infrastructure, USD 40 billion in communication and around USD 30 billion in water (see Figure 2).

Up to 60% of infrastructure investment demand is in emerging markets. UNESCAP estimates that in the developing countries of Asia and the Pacific alone, an additional USD 900 billion per year of infrastructure investments are needed.

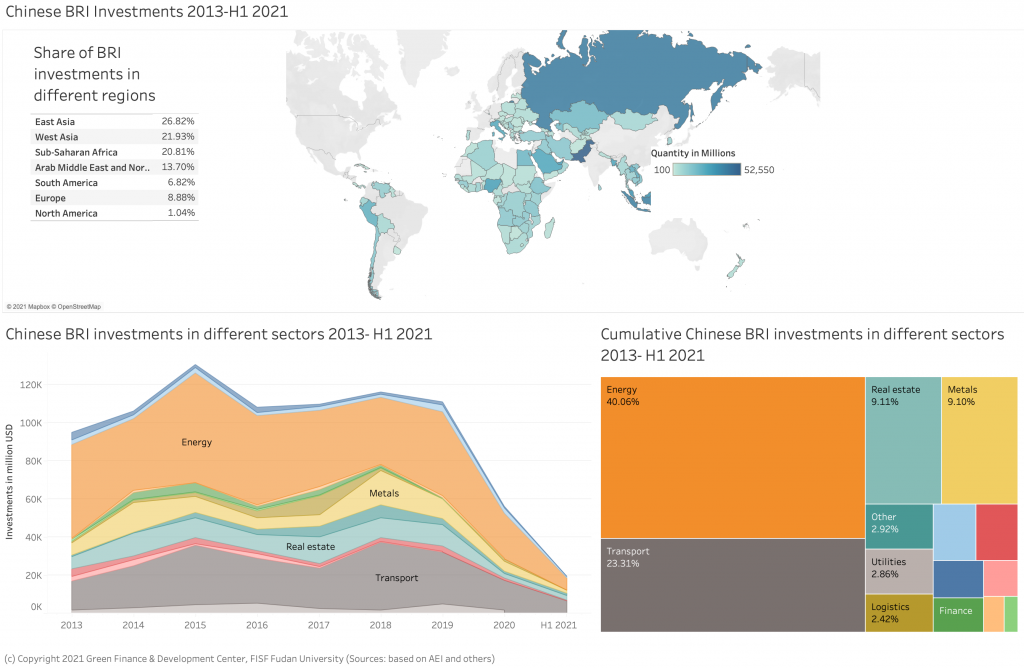

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investments

Over the past years, China has become one of the most important sources of infrastructure funding in the developing world through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Since 2013, China has financed about USD 750 billion in BRI projects, particularly in the energy and transport sector (see Figure 3) [3]. Yet, this is far insufficient from closing the infrastructure investment gap.

The need for international cooperation

To mobilise more financing for infrastructure in emerging markets, it is paramount to deepen international cooperation between relevant stakeholders, including private investors, in infrastructure finance. Cooperation will not only allow for better distribution of resources and less friction (e.g., in the application of technology and process standards) but also result in better utilisation of existing capacities and capabilities of different developers and financial institutions involved in infrastructure finance.

Infrastructure investments require a financing mechanism to pool expertise and finance from multiple parties while limiting different types of projects, sector and country risks and maximising both returns and infrastructure delivery. The most important and successful mechanism to achieve that goal is project finance.

Particularly project finance is an important tool for closing the global infrastructure gap.

Project finance

Project finance is a form of limited recourse lending and a form of governance structure. In project finance, the investors and particularly the lender assumes the risk of a project before the project generates returns and financing conditions and agreements are based on the project itself, rather than the balance sheet of the project owner(s). Project finance thus limits the liability of the different project owner(s) involved in the project, theoretically putting the project’s debt “off-balance sheet” for the owners (in practice, however, owners would rarely exercise this non-recourse right). The concept of limited liability that is ensured through the project revenues rather than through the sponsors’ balance sheets is also referred to as non- or limited-recourse lending. The concept of non-recourse is ancient – e.g., it was already used by merchants and ship owners to finance and share risks for conducting sea voyages for overseas trading. Project finance became an important tool in the 20th century, e.g., to develop oil fields in the US and the UK. This form of financing is thus different, for example, from financing a project through corporate financing (e.g., through a corporate loan), where the borrower would take on liability beyond the project.

Project finance as a tool for risk-reduction

Project finance, therefore, requires detailed risk evaluation, risk mitigation and risk management throughout the whole project lifecycle – with a special focus on the earliest phases of the project. Project risks need to be effectively allocated to the parties best able to manage and bear them, while negative net-present value (NPV) projects should be identified and excluded early.

Project finance aims to reduce and manage risks, while maximising returns and infrastructure development. It allows project owners and sponsors to:

- Raise relevant funds to also pay for the high transaction costs in the project preparation, which can represent, on average, between 3% to 5% of the total project costs;

- Reduce information gaps by maximising due diligence on a specific project through independent consultants, insurance/legal/financial advisors, reporting and controls;

- Reduce principal-agent conflicts due to the high leverage rate of projects, requiring much of project cashflows to be paid to creditors first in the cash flow waterfall, reducing cash-flow diversion actions;

- Reduce financial distress of project owners, as project debt is ideally off-balance sheet (although project owners rarely ‘walk away’);

- Allow for financing flexibility, with different sources and instruments of finance (e.g. senior debt, junior debt, mezzanine debt, equity, export credits) to adjust for the project’s idiosyncratic risks and needs;

- Possible tax advantages through moving revenues and losses around in different countries.

Project phases

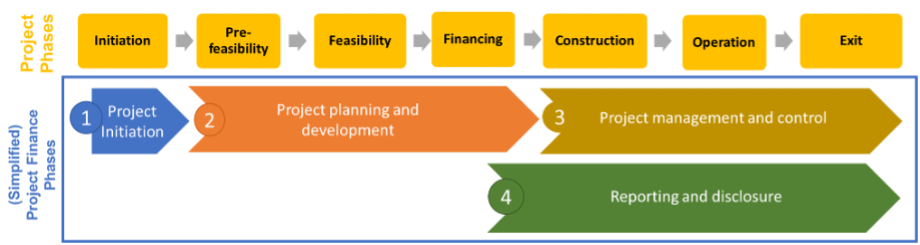

For projects to get off the ground, they typically go through several phases, each with their own goals and process steps. With the goal to study project financing and the possibility of tripartite cooperation in project financing, this study focuses on the following phases (see Figure 4):

- Project initiation

- Project planning and development

- Pre-feasibility

- Feasibility

- Financing

- Project management and control

- Construction and completion

- Operation

- Project exit

- Reporting and disclosure (partial overlap with phases 2 and 3)

These phases are partly clearly distinguishable (e.g., as some legal licenses or financing is required to actually start project construction), while other elements of these phases overlap or can be done in a different order (e.g., sometimes construction partners can already be identified in the pre-feasibility phase, at other times they might be identified in the feasibility phase or even in the construction phase).’Ä

Project finance is already highly complex, due to the diverse risks (e.g. technical, legal, political, environmental, social) that can arise over the decades while a project is being implemented. Project finance the numerous different interests of involved parties in projects and the various operating models (e.g. “BOT”, “BOO”, “DBFO”) that require different capabilities, international project finance that engages parties from different countries with different expectations is even more challenging.

Project Finance Structure

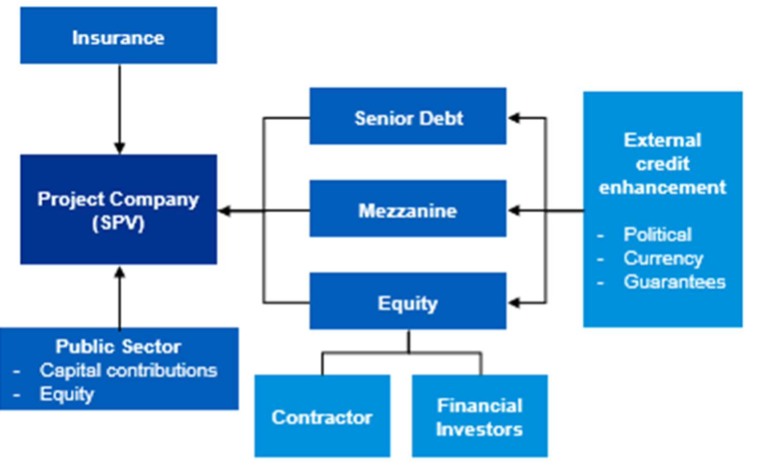

With the project company, or the special purpose vehicle (SPV), sitting at the centre of the project, all relevant financing agreements are between the various involved parties and the SPV. The SPV is financed through different forms of debt (e.g., senior debt, junior debt), mezzanine or convertible debt, as well as equity. Its financing might be enhanced by guarantees by e.g. development finance institutions, export credits, and insurances to protect e.g. against political or catastrophic risks, as well as exchange rate hedging mechanisms.

Operating models in project finance

Different investors and financial sponsors have different responsibilities, rights and bear different risks in project finance. As project finance is characterised by a high leverage ratio, of often e.g., 20% equity and 80% debt, project finance lenders typically require comprehensive covenants and security packages.

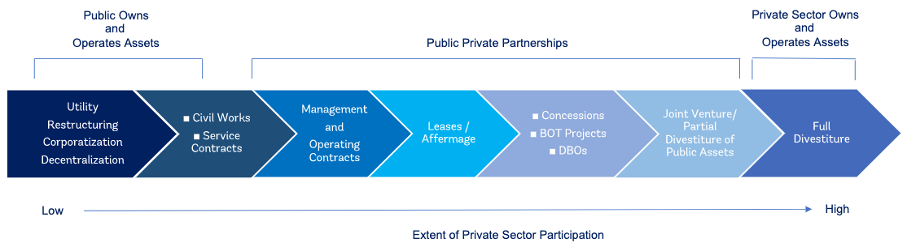

Many infrastructure projects (e.g., roads, energy projects) will involve both public actors and private partners. Such public-private partnerships (PPP) take a wide range of organisational forms, depending on the local circumstances, laws, project, and experience of the actors (see Figure 6).

Depending on the arrangement, the responsibilities and activities of the SPV within the PPP will vary, particularly in regard to risk transfer to each party, responsibilities of investments, and the control of ownership of the assets in different project stages. For example,

- In a concession agreement, the public authorities would grant a concessionaire the long term right to use the specific utility assets, who would also be responsible for operations and some investments. However, the public authority would remain the owner of the asset and would be responsible for the replacement of larger assets. During the concession, the concessionaire obtains most of its revenues from the customer through a direct relationship (including end-consumers), while the concessionaire pays a fee to the authority. At the end of the concession, all assets revert back to the authority;

- In a build own operate transfer (BOOT) project, the authority grants a right to the SPV to develop an asset (greenfield project) by the SPV. The SPV finances, owns, constructs, and operates the asset for the time of the agreement. The SPV obtains its revenues typically through a fee charged to the utility/government (often a single off-taker), rather than e.g. from end-consumers. At the end of the project concession, the asset is typically transferred to the authority or sold to another party.

| Name | Definition | Relevance |

| Build-Operate-Transfer (BOT) | In a BOT project, the public sector grantor grants to a private company the right to develop and operate a facility or system for a certain period (the “Project Period”), who operates it commercially for the project period, after which the facility is transferred to the authority. The public authority is the sole or one of the owners of the SPV and thus provides some financing. | Suited to projects that involve a significant investment and operating content, and are widely used in infrastructure projects. BOT projects are often initiated by governments or relevant authorities. |

| Service Contract | Government outsources specific service provision to a private company, e.g. design, construction, maintenance or operation of infrastructure, while financing and revenues are within the government. | For small scale projects within a well-established service sector. |

| Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT) | A variation of BOT. In a BOOT model, the private company finances, operates and owns the project for the project period, after which the facility is transferred to the authority (often at no cost). | Especially suitable if the government has a large infrastructure financing gap. Also widely used in infrastructure projects. Initiators of such projects can also be commercial project sponsors. |

| Build-Own-Operate (BOO) | A variation of the BOT, where the SPV retains ownership of the asset into perpetuity and can sell it to another investor; possibly also in a fully private deal without involvement of public authorities (and thus not considered a PPP). | Used depending on the local circumstances, for example when no public partner would be required or where the public authority does not require to re-take ownership. |

| Rehabilitate-own-operate (ROO) and Rehabilitate-Own-Operate-Transfer (ROOT) | Used for the rehabilitation of an existing infrastructure (rather than construction of a new one), but otherwise similar to BOO or BOOT. | Suitable for capacity upgrading, e.g. for roads. |

| Design-Build-Finance-Operate (DBFO) | The private sector provides assets, finance (debt and equity) for construction and operation. The public authority pays for the asset on completion and for the services provided. It is considered a “output-focused contract”. | Used for example for road construction |

International cooperation on project development in the BRI

International cooperation for infrastructure projects can accelerate capital mobilisation (e.g. from various sources of commercial and development finance), as well as improve access to relevant technical capabilities – all of which help better manage risks and improve the service delivery. There have been numerous successful examples of cooperation in investment, financing, and project implementation with Chinese partners, such as the construction of a 100 MW wind park in Kazakhstan: the USD95.3 million was financed by two development banks – the London-based EBRD and the Beijing-based AIIB, the Green Climate Fund (GCF), as well as the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC). The SPV Zhanatas Wind Power Station is owned and run by China Power International Holding (CPIH) in partnership with Visor Investment Coöperatief. The SPV is responsible for the construction and operation of the wind farm and the transit cable connecting the facility to the grid.

To further accelerate international project financing with Chinese partners, common standards are particularly relevant regarding green project finance to allow a global transition of infrastructure in accordance with the Paris Agreement and global biodiversity targets.

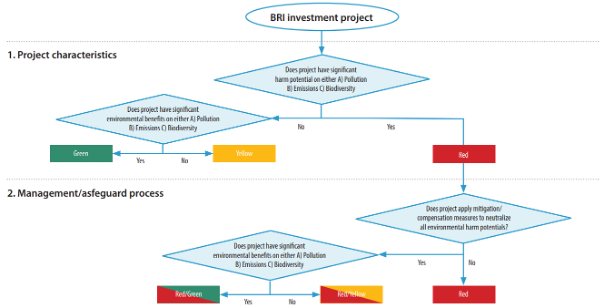

An important milestone for better cooperation between Chinese and international investors was achieved in December 2020, when the BRI Green Development Coalition (BRIGC) published the Green Development Guidance for BRI Projects (baseline study). The study, which was backed by relevant Chinese ministries and regulators (e.g., MEE, CBIRC, NDRC) as well as their affiliates, aims to guide Chinese investors and developers in reducing environmental risks in the BRI and set project finance standards that are aligned with international standards. A key element of the Guidance is the “Traffic Light System” that provides a clear and simple color-based categorisation of projects into either green, yellow and red depending on their environmental risk and impact. Green projects have no significant harm on any of the three environmental dimensions: pollution, biodiversity and climate, and improve environmental outcomes in at least one dimension. Red projects are all projects that risk significant harm to the environment in any of the environmental dimensions. Projects in the “yellow” category “Do No Significant Harm” (DNSH) to any environmental aspect, and any residual environmental harm can be mitigated by the project itself through affordable and effective measures within reasonable boundaries. To account for local realities, the traffic light system then provides guidance on how to mitigate or compensate for environmental harm and thus guides project developers on how to improve their project color from red to red/yellow and red/green.

Recommendations to accelerate international cooperation in project finance

However, as differences between Chinese and international project financing practices continue to exist, co-financing and co-operation in project finance between Chinese and international partners remains challenging.

The handbook was therefore written for Chinese companies (including state-owned enterprises and private companies) to apply project finance in overseas infrastructure projects, especially in emerging markets. It particularly aims to facilitate the cooperation between Chinese companies, Chinese and international financial institutions in third markets. The handbook is based on desk research, expert interviews and focus groups and an in-depth comparison between current Chinese and international infrastructure finance practices across the project pipeline.

This handbook is intended to bridge the gaps between Chinese and international project finance instead of challenging or elaborating on either Chinese or international project finance best practices. Given this goal, the handbook first provides descriptions of current Chinese and international practices in infrastructure project finance (See Appendix), and identifies 8 major gaps between these two practices through a gap analysis (Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.):

- Ways of project initiation: A small number of Chinese-led infrastructure projects were initiated by G2G channels and thus are hard to co-finance with international investors;

- Approaches to risk analysis and identification: International project finance requires a more exhaustive analysis of risks with higher granularity.

- Approaches to Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA): International FIs often have higher requirements on environment and social risk due diligence.

- SPV governance: Differences exist in the independence of the oversight, political risk considerations, and understanding of conflicts of interest.

- Sources of financing: International project finance usually has complex structures that include diverse sources of financing and more private participation.

- Role of guarantees: Guarantees in Chinese project finance are often used as a “safety net” for general unclear risks instead of addressing specific risks.

- Environmental and Social Management System (ESMS): A project-level ESMS, including an effective grievance mechanism, is lacking in most Chinese projects.

- Environmental and social reporting and disclosure: E&S reporting and disclosure are more common in international project finance, mainly because they are required by international lenders and investors.

To address the gaps identified above, 8 recommendations are developed to accelerate international project finance with Chinese participation (Fehler! Verweisquelle konnte nicht gefunden werden.). These recommendations address Chinese project sponsors interested in attracting international capital in overseas infrastructure projects, but are also applicable to international partners interested in engaging Chinese companies and financial institutions.

The recommendations are based on extensive literature research, interviews and workshops with experienced practitioners from Chinese companies and financial institutions engaged in overseas project development, as well as with international financial institutions. The recommendations aim to close the identified gaps along the project finance lifecycle:

Recommendation 1: Focus on high-quality and transparent project initiation, utilising a broad range of project initiation mechanisms, such as project initiation facilities or early-stage project developers;

Recommendation 2: Strengthen independent risk analysis and risk identification early in the project development stage to better allocate risks to relevant partners;

Recommendation 3: Strengthen environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) to not only obtain a local ESIA license, but to clearly reduce the environmental and social risks of projects;

Recommendation 4: Improve governance of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV) to reflect the different interests of the project stakeholders and minimise conflicts of interests, by providing transparent processes, oversight, and control mechanisms;

Recommendation 5: Utilise multiple sources of financing in different project phases, from early-stage financing through loans, export credits and equity to later stage financing through, e.g., project bonds or institutional debt funds;

Recommendation 6: Minimise use of sovereign and corporate guarantees, explore diverse credit enhancement instruments;

Recommendation 7: Diligently set up and implement an environmental and social management system including an early warning system and a grievance mechanism in order to be able to quickly react to risks and events in a consistent and strategic manner;

Recommendation 8: Report regularly and transparently on environmental and social performance, ideally prepared by independent consultants and auditors.

By incorporating these recommendations, three interrelated advantages could be generated to accelerate international infrastructure project finance:

- Better identification and management of infrastructure project risks;

- Improvement of ecological and social sustainability of projects;

- Reduction of sovereign debt risks, particularly in emerging markets.

While infrastructure project finance will remain one of the more complex forms of financing, not only in emerging economies, we hope to provide some relevant guidance to reduce risks and increase opportunities through international cooperation and to allow for a new era of sustainable infrastructure development.

Comments are closed.