For a Chinese version, click here.

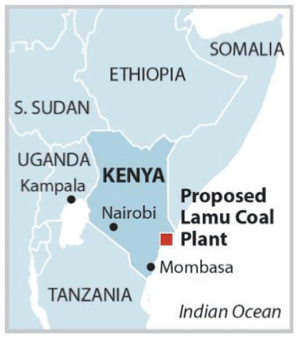

On July 26, 2019, Kenya’s National Environmental tribunal ruled that the environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) license for the Lamu coal fired power plant in Kenya was insufficient and that the construction had to be stopped.

While this ruling explicitly states that this is not a legal case against coal-fired power plants, it nevertheless comes after 3 years of intense campaigning against what would be Kenya’s first coal-fired power plant: local NGOs and stakeholder groups organized under the deCOALonize umbrella and brought the legal case against the power plant’s consortium and the Kenyan government agency that issued the ESIA license in the first place.

The Lamu 2 billion USD coal-fired power plant is built by Chinese enterprises, particularly two subsidiaries of PowerChina Group (Sichuan Electric Power and Design and Consulting, Sichuan No.3 Power Construction Company) and China Huadian Corporation Power Operation Company and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) finances the plant.

Background of the Lamu Coal Fired Power Plant

Coal energy in Africa

Coal fired power plants had been the backbone of many country’s energy networks. For investors, coal-fired power plants have proved to be a sound investment with steady, and easily calculable returns, making them assets with controllable risks. This has allowed investors to gain substantial experience in valuing investments in coal-fired power plants.

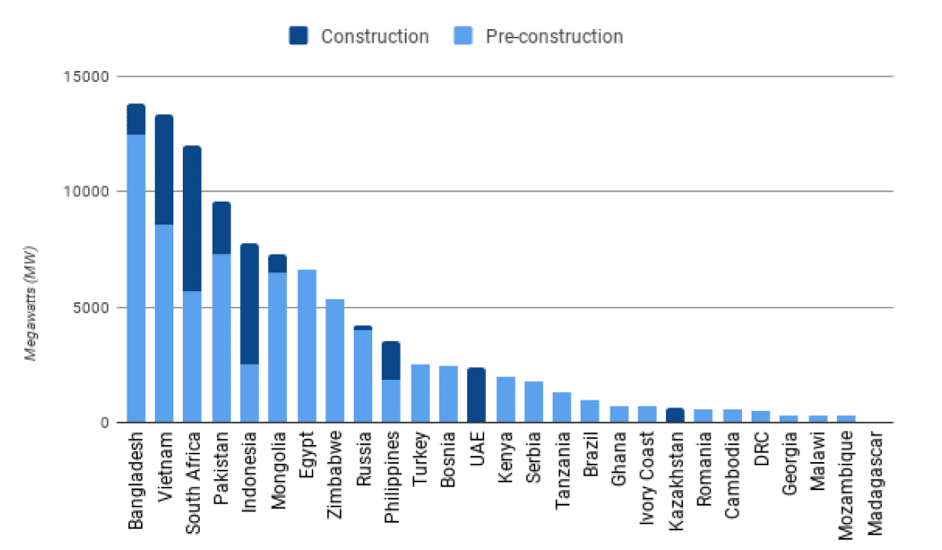

On the world’s stage, Chinese, Japanese, Korean and American were among the top investors and engineering, procurement and construction companies (EPCs) to invest in coal-fired power plants. In 2018, of the 399 GW of coal-fired power plants under development outside of China, Chinese financial institutions and corporations have committed or offered funding for 102 GW coal-fired power worth US$ 35.9 billion.

However, due to climate and environmental concerns, coal-fired power plants have become increasingly under scrutiny. A number of coal-fired power plants have been postponed or shelved due to stakeholder-activism. Among them are the Rampal power station in Bangladesh due to potential harm to the UNESCO World Heritage Sundarbans, the Tamil Nadu 3.6 GW coal-fired power plant in India, due to inadequate Environmental Impact Assessment, or in Sri Lanka, where local residents pressured the consortium to build a LNG plant instead of a coal plant.

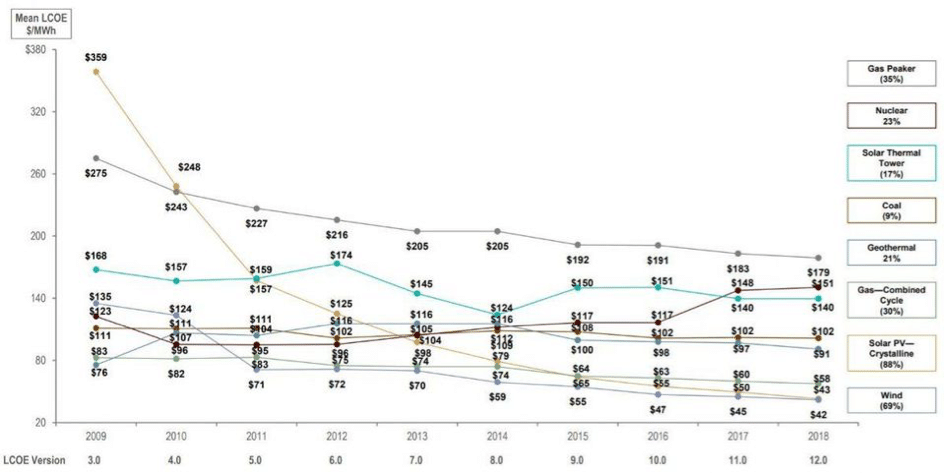

At the same time, the cost of renewable energies have made coal-fired power plants increasingly uncompetitive. According to a study by Lazard, annualized levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for solar photovoltaic and wind energy have dropped by 88% and 69% respectively from 2009 to 2018, while these costs for coal and nuclear have increased by 9% and 23% respectively (see Figure 2). This risks that energy from most coal-fired power plants will be more costly than renewable energy.

Kenya’s energy needs

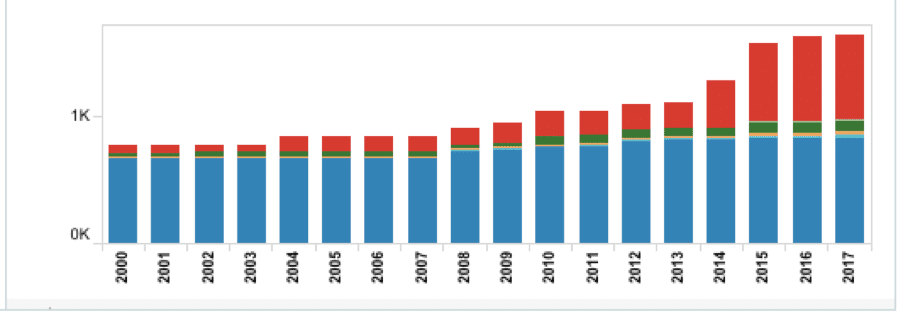

Kenya in 2019 had no operating coal-fired power plant. It relied mostly on renewable energy supplying 1,6 GW in 2017, particularly hydropower (827 MW), bioenergy (85,2 MW) and thermal power (672,9 MW). Renewable energy generation in Kenya has grown by over 200% from 2000 to 2017 (see Figure 3).

But with energy consumption growing by 272% from 2,93 TWh in 1990 to 7,98 TWh in 2016, the Kenyan government saw a need to improve its energy supply: Based on the 2011 Least Cost Power Development Plan (LCPDP) issued by the Energy Regulation Commission (ERC), a semi-autonomous unit of Kenya’s Ministry of Energy, Kenya forecasted a 13,4% annual energy demand load growth and a 11,4% average annual peak demand load growth.

Thus in the middle of 2013, Kenya’s government decided to build a 1050 MW coal fired power plant in Lamu – which would be the first coal-fired power plant in the country.

The Lamu coal fired power plant

The plant was to supply 1,050 MW of energy, first with imported coal from South Africa and Zimbabwe and later with the newly discovered coal reserves in Kenya’s Kitui county Mui Basin.

After several rounds of bidding, the Kenyan government selected a consortium called AMU Power Company Limited in September 2014. The consortium included:

- Centum Investments (Kenya) (owning 51%),

- Gulf Energy (Kenya) (owning 49%),

- Sichuan Electric Power and Design and Consulting (China) – subsidiary of the PowerChina Group,

- China Huadian Corporation Power Operation Company (China), and

- Sichuan No. 3 Power Construction Company (China) – subsidiary of the PowerChina Group.

The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and the consortium signed the financing agreement for the project on June 8, 2015. According to this agreement, ICBC would arrange around 900 million USD export credit financing and would also serve as the financial advisor for the project. Accordingly, the Lamu project would be funded through 75% debt and 25% equity. Construction start date was set to September 2015 and the power plant was expected to be finished within 30 months by about 3,000 workers, including 1,400 Chinese workers.

The difference between a political agreement and a license

Before construction could start and the power generation license could be given, an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) needed to be undertaken with the goal to prove protection of basic environmental and social safeguards. AMU Power Company engaged Kurrent Technologies Limited to undertake the ESIA. The purpose of an ESIA process was to assist a country in ensuring social and environmental sustainability when commissioning projects, in line with the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In this process, stakeholder groups, such as Save Lamu, a coalition of 30 community organizations objected many of the claims of how Lamu would improve local lives. Save Lamu’s leader Omar Elmawi argued:

“We at Save Lamu we are totally pro renewables and anti coal. There is nothing at all as ‘clean coal’. Coal is dirty energy, and by all means we strongly campaign against any plans to build a coal plant in Lamu”. (Source)

The consortium also ran into problems for example with, e.g. land acquisition/land compensation. Only in September 2016, the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) issued the Environmental Impact Assessment License to AMU Power Company based on the ESIA. In February 2017, the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) of Kenya argued that all environmental, technical and economic issues raised by Save Lamu had been addressed and approved the construction of the project. Immediately, Save Lamu filed a lawsuit against AMU Power Company and the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA) for not following the procedures and obtaining the ESIA license unlawfully.

Nevertheless, in May 2017, negotiations for the power purchase agreement (PPA) reached their conclusion: Amu Power and China Power Global signed a $1,9 billion power PPA. And finally, in June 2017, construction of the Lamu project started.

Yet, pressure kept mounting – both through regular protests and demostrations in Kenya, but also due to international scrutiny: four US senators urged the African Development Bank to not invest in the Lamu coal fired power plant due to ecological reasons and many large investors urged the American conglomerate GE not to invest its money into Lamu.

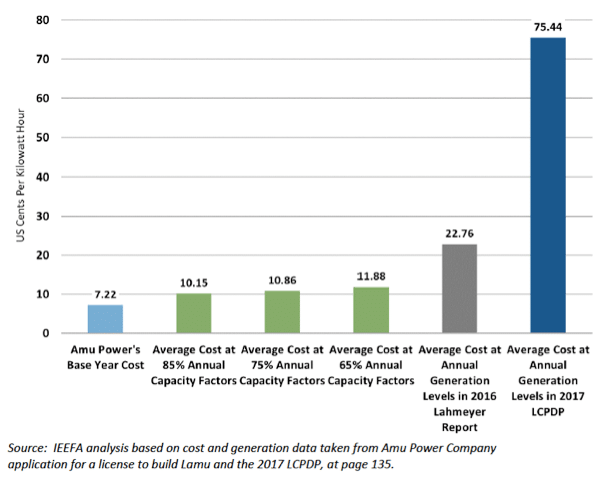

Also, due to slower than expected energy demand growth, the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC) of Kenya instructed AMU Power to half Lamu’s capacity for its 3 stages, from 350 MW to 150-200 MW. As a result of lower usage of capacity and thus lower efficiency, the average cost for a kWh produced at Lamu would go as high as 75 US cent – 10 times as much as its cost at full utilization (see Figure 5). As a consequence, retail prices for electricity in Kenya would increase beyond what was forecasted.

The legal proceedings

From May 2017 to June 2019, the National Environmental Tribunal at Nairobi oversaw the case between the 6 appellants (including Save Lamu) and the two defendants – the National Environmental Management Authority and Amu Power Company Limited.

On July 26, 2019, the court decreed that the environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) license was not given according to the law, as both the consortium and the NEMA failed to follow procedures for stakeholder participation and missed to properly evaluate alternatives. With this, it effectively stopped the construction of the power plant as long as the grievances were not fully addressed.

Overall, while the court did not rule on the viability of coal fired power plants, investors of the plant could be rightfully worried: costs of the project continued to rise while the project had actually not even commenced.

Lessons learnt and recommendations

For investors from China or elsewhere, the Lamu coal fired power plant can serve as an important learning example: while the national government originally both supported the construction of a coal-fired power plant and issued all licenses (albeit with delay), local environmental and social activism can derail investment projects. For investors this means:

- investors need to ensure that not only the government, but also the broader society supports the projects. This is particularly important in democratic and rule of law states, where business-to-government agreements are insufficient to ensure the implementation of a project.

- Therefore, investors should engage with stakeholders through transparent communication and sharing of their analyses.

- In this, investors should clearly calculate and lay out alternatives for specific investments, particularly for controversial ones such as coal-fired power plants. Kenya’s capacity for renewable energy is untapped and cost for renewable energy generation has decreased substantially. By properly evaluating different options, investors will have both better returns and a clear line of argumentation with government and civil stakeholders.

- investors need to calculate and include the risks and costs of stakeholder engagement and legal proceedings, which raises the cost of projects.

- Chinese and international investors should adhere to international investment due diligence standards, particularly the Belt and Road Green Investment Principles (GIP), as well as the Equator Principles. These principles include UN SDGs and the Paris Agreement on combating climate change – making investments in greenhouse gas emitting energy unprincipled.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.

Comments are closed.