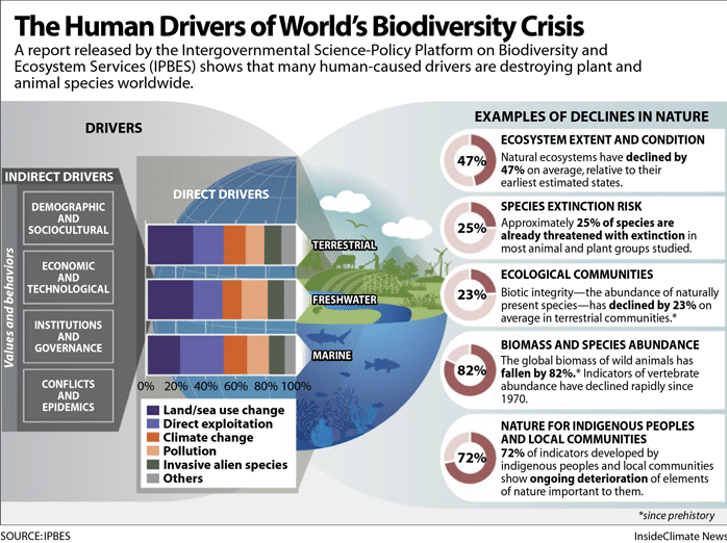

Natural ecosystems have declined by 47% compared to their earliest estimated state, 25% of species are already threatened with extinction, the biomass of wild animals has decreased by 82%. The losses to biodiversity and its consequences on both economies and our Earth’s well-being are becoming more evident, while the world is struggling for to develop the post-2020 biodiversity protection framework at the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Conference of the Parties (COP) in Kunming in October 2020. Progress for biodiversity protection is even more difficult than protecting climate. In this article, I propose four axioms, to help move ahead in biodiversity protection in the Belt and Road Initiative and more broadly.

Human activities risking biodiversity and pushing the planetary boundaries

Biodiveristy is threatened due to a number of human activities, such as construction of infrastructure cutting into natural habitat, use of fertilizers in agriculture and similarly wastewater from human activities that pollute our waters and soils, and emissions from industry, energy and transport that pollute our air.

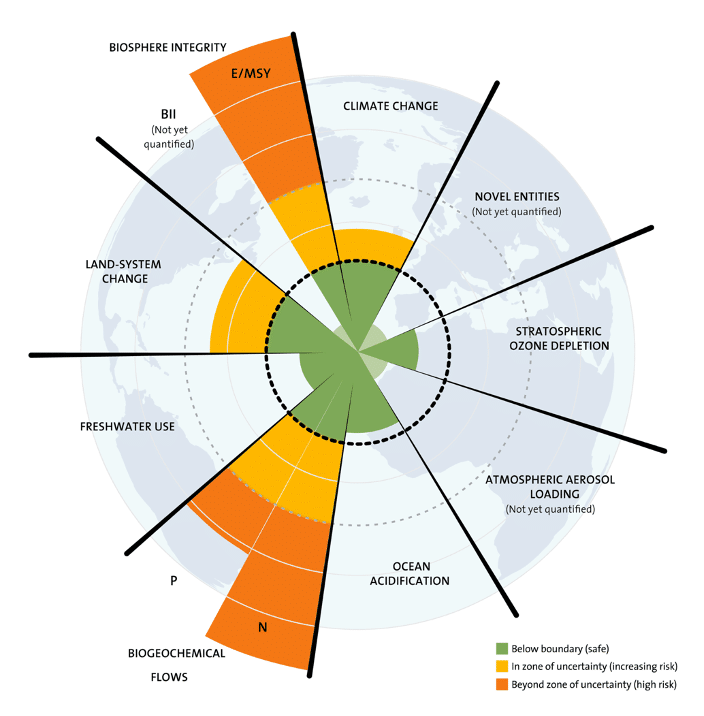

The impacts on biodiversity of human activities are so alarming that in 2009, an international researcher group has proposed the concept of planetary boundaries or “safe operating space for humanity”. The researchers found that the integrity of our biosphere and biodiversity have reached alarming levels, much higher than climate change.

Biodiversity Finance

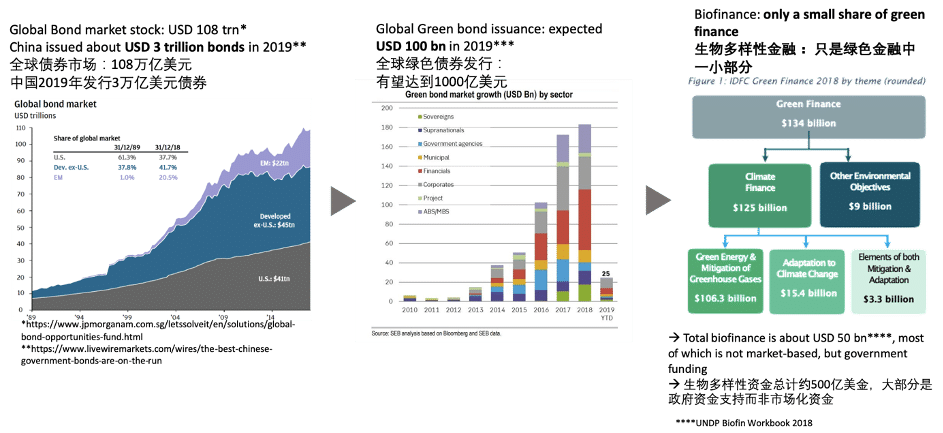

To deal with the risks from the loss of biodiversity, finance is said to play an important role. Taking a page from the playbook of finance to deal with climate change (e.g. climate finance, carbon finance), biodiversity finance should ideally fill two gaps to drive biodiversity conservation: 1. Mobilize different forms of capital to accelerate the investments into economic activities that are protecting biodiversity, and 2. Include the risks of the loss of biodiversity in investment decisions.

However, so far biodiversity finance has not delivered. According to the UNDP, global biodiversity finance amounts to a bare USD 50 billion, most of which from government funding or donations, and only about 15 billion of private capital for biodiversity finance. This compares to about 100 billion USD private issuance of green bonds (mostly for climate and pollution protection) in 2019 and a global bond market of USD 108 trillion. In other words, the global bond market alone (as just one of the ways of financing projects, next to e.g. equity, loans, governments) has a volume that is more than 2.000 times larger than the total volume of investments flowing into biodiversity conservation.

Four Axioms of Biodiversity Finance

To design a possible pathway forward in the protection of biodiversity, particularly in regards to the preparation of the Post 2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, I want to propose four obvious, but important axioms:

1. Not all nature is bankable, nor does it need to be

Much of the biodiversity finance world is embarking on an important endeavor to improve natural capital accounting. The goal of natural capital accounting is to give values to specific natural resources and the ecosystem services they provide. As an example: a river provides drinking water, water for industrial use, water for fish which can be caught and eaten etc. This has an economic value for humans. However, the economic value of nature is much different from say the value of a machine: a machine’s value can be both calculated in terms of its production cost (e.g. how much does it cost to produce the machine) and its output value (e.g. how much production value is generated through the machine). For nature, however, both calculations are impossible. First, there are no clear cost in creating nature. Second, the output is undefined. We don’t understand all interdependencies of nature and thus cannot clearly value it. Nor do we know the yet undiscovered economic values of natural resources, for example for future pharmaceutical products. Even for today’s “values” of nature, we fail to put a price on it. What is, for example, the value of being able to breath fresh air, not only as a health concern, but as a personal enjoyment? What is the economic value of a wild animal being able to roam in the wilderness?

A simple comparison is the value of a person’s life versus his/her salary. The salary of a person is the value of the service the person provides, but the person itself is not bankable or has a defined value.

2. Biodiversity finance is interacting with other sustainability goals

The World has agreed to focus its development on 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) until 2030. These include social goals, economic, as well as environmental development goals. While some activities are re-inforcing each other, other activities in support of the SDGS are contradicting. A simple example is activities supporting SDG 9 – industry, innovation and infrastructure, such as increased investment into transportation infrastructure. These activities most certainly leads to destruction of natural habitats and therefore in direct contradiction to biodiversity conservation (e.g. SDG 15 – life on land).

The balance between investments into different SDGs is a constant dilemma for policy makers and investors. As dilemmas can never be solved, but need to be managed, it is crucial to better understand the interdependencies. This allows to maximize the returns on development while minimizing the risks of violating other SDGs.

3. Biodiversity conservation needs more leadership and role models

Biodiversity conservation has seen a few strong proponents, particularly several NGOs, such as WWF, Friends of the Earth, Sea Shepherd Conservation Society as well as prominent figure such as Sir David Attenborough, who is the filmmaker responsible for many world-renown BBC nature documentaries. While these leaders have given rise to a better understanding of the beauty of and threats to biodiversity, much of the economy and society has failed to adapt its behaviors to better protect biodiversity (otherwise, we would not see such a drastic decline in biodiversity).

Thus, more leadership, particularly political, business and individual leadership, is required. This leadership needs to fulfill two criteria: First, where available, these leaders should show alternatives for current activities. These can include nature-based solutions for infrastructure rather than concrete infrastructure, plant-based diets rather than meat-heavy diets etc., use of reusable bottles and bags rather than plastics. Second, these leaders need to push through changes that deviate from current behaviors. As changes are always perceived as losses and thus are thus evoking fear and uncertainty in most people, leaders should stop telling everyone that we have “win-win-situations”. It’s a lie! Changes in investment patterns, in business activities and personal behaviors are required that are painful and scary and that require real leadership. These changes will lead to a gain in one area (e.g. sustainable business activity, biodiversity conservation, personal well-being), but they are most definitely a loss in another area (e.g. non-sustainable business and personal activities).

4. Biofinance requires international cooperation paired with local action and responsibility

Biodiversity protection is very different from climate protection in one crucial point: greenhouse gas emissions in one place has climate impacts around the whole world. As a consequence, only global solutions are really effective to deal with climate change.

This is different for biodiversity conservation. Biodiversity conservation is much more localized depending on local actions to protect the habitat for specific species. To put it bluntly, who in Australia cares about the health of the insect stock in Germany, which has become the topic of one of the most successful public referendum in 2019 in Southern Germany’s State of Bavaria. Also, despite international effects, e.g. of plastic waste or of chemicals, most of it affects local communities through the pollution of rivers or arable land.

Yet, international cooperation is crucial for two important points: First, particularly migratory species don’t follow countries’ borders, but walk, fly, or swim across countries’ borders. Many regional cooperation mechanisms have been successfully implemented to form transboundary protected areas (TBPAs) to deal with migratory species. The first international natural protection area was established between the USA and Canada’s in 1932 for the Waterton-Glacier National Park. As of 2007, there were 227 transboundary protected areas, most of which in Africa and Europe. Second, for biodiversity finance to be successful, international standards need to be established, e.g. for accounting, regulation and risk management. Only international standards will allow to create a fluid and thus efficient market that channels investments in those areas with the highest impact and returns, make investments and reporting comparable and therefore more effective. In addition, international standards will support creating a level playing field for investors and business alike which ideally avoid that some companies have higher costs for doing business in an environmentally-friendly way, while others undercut prices by being non-compliant.

Biodiversity Finance in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

The countries of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are at particular risk of losing biodiversity, due to two interrelated reasons: First, in many countries of the BRI, economic activity is still lower. As a consequence, many areas that are underdeveloped have a more pristine natural habitat. At the same time, these countries have much economic growth need and potential. China promised to invest in infrastructure, such as transport and energy, to accelerate economic development. However, this leads to not only more economic development with its indirect effects on biodiversity, but also to the direct destruction of natural habitat through linear infrastructure construction (as described, for example here). As a consequence from infrastructure development along the BRI, 4,138 animal and 7,371 plant species along the BRI are endangered.

To ensure that planetary boundaries are not further stretched, but biodiversity is protected, the following steps should be urgently taken:

- Accelerate the legal protection of specific areas based on science-based targets that must be protected no matter the cost. This means that nations need to protect not only their most favorite species, such as the panda or the tiger, but their most important and threatened species. They also need to protect areas that are relevant for nature, and not those that are merely irrelevant for economic activities. IUCN provides 6 categories of protected areas to allow for different interactions between humans, economic and natural activities.

- Accelerate financing models for protection and interaction with biodiversity that allow for financing the implementation and safeguarding of protected areas, e.g. through blended finance instruments, eco-tourism, ecosystem revenues.

- Use big data and AI to better understand and evaluate interdependencies of nature, human and economic activity. Massive amounts of data are already created through sensors, satellite pictures, etc. that allow us to analyze impacts of economic activity on biodiversity. While some governments are wary to use these data in fear of too much transparency, both private and public big data analysis through AI can help make better investment decisions that minimize the risks and deal with the interdependencies in a more efficient way.

- Accelerate political leadership on all levels, from international to national to regional to local levels for the protection of biodiversity by laying the groundworks through better education about the risks of biodiversity loss, the beauty of biodiversity and the potentials of human actions for doing good and for doing bad.

- Accelerate international cooperation for providing standards for finance for biodiversity. This means, for example, the requirement for more transparency for financial institutions in regards to biodiversity impacts (similar to emission accounting), e.g. by requiring disclosure on a comply or explain basis until 2025 and then mandatory disclosures for international financial institutions. Biodiversity conservation targets should be more clearly integrated into for example the Green Investment Principles (GIP) of the Belt and Road, as well as in the Equator Principles.

- Don’t reinvent the wheel. Biodiversity conservation and biodiversity finance have bene important topics in select circles for decades. Much work and research has been published how to accelerate finance, include biodiversity protection into investment decisions (e.g. IFC Performance Standards). Investors and regulators should not feel the need to build new tools, but should have the leadership guts to actually push for the application of existing standards, or if they find current standards insufficient, explain why and have more ambitious standards, not less ambitious ones.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.

Comments are closed.