The European Union Project EC-Link published the new report by IIGF Director Christoph Nedopil, Ying Cui, Andreas Kress and Marie Kleeschulte on “Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) & Green Urban Finance”. In this article, we provide a short summary of the report.

About the report

International cooperation in frameworks like the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) provide ample opportunities for economic growth, high returns on investments and social development. At the same time, investments for development risk an acceleration of pollution, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and loss of biodiversity if we follow current trajectories. Current policies and investment trends are insufficient to tackle the goal of having a zero-carbon society by 2050 in Europe, in China and in the BRI.

To understand the current situation and potential future trajectories of green urban finance, this report analyzes green urban finance developments in China, Europe and the BRI. We provide an overview of the green finance policy perspective, analyze developments of public and private finance and provide relevant 5 green urban finance case studies from Europe (Paris (FR), Litoměřice (CZ) and Essen (DE)) and China (Shandong, Shenzhen) among many other smaller examples.

Green Urban development and the need for green finance

To achieve the goal of green development, cities play an outsized role: in the year 2030, cities are expected to be responsible for 60 to 80% of global emissions. More than 60% of the global population will live in cities by 2050 and 600 mega-cities are expected to generate 60% of the world’s GDP by 2025. Consequently, the range of challenges posed by climate change, economic and demographic transformations in the region is huge, with governments and city mayors facing increasing pressure to find sustainable solutions, e.g. for sustainable transport, sustainable urbanization, or the fourth industrial revolution or simply industry 4.0 for economic activity. Ensuring that cities are sustainable is critical for the future of our planet and our population.

Accordingly, green investment needs to tackle the challenge to build green urban centers far exceed what public resources can provide, in Europe, in China, in the BRI countries and globally. Attracting more commercial finance and private expertise to close several trillion USD funding gap for green urban development is a critical challenge. Meaningful increases in private green investment will require removing key constraints on private sector participation in climate infrastructure and building effective institutional structures to mobilise, steer and manage such finance.

In our report, we found that in urban areas, it is particularly the investment in the transport sector, industrialization and sustainable urbanization that have a great influence on future green growth trajectories. Therefore, in addition to policies on renewable energy, energy efficiency, clean transport, green urbanization (such as buildings) on the demand-side, policy makers have to improve policies for green domestic and cross-border finance. Besides overseas finance, the report also looks at domestic green finance markets in BRI countries.

Green finance policies within the BRI countries

Many BRI countries are emerging economies. They not only rely on foreign private investments to drive economic growth, but also investments from development finance institutions, such as multilateral or bilateral development banks, such as China Development Bank (CDB), China Exim Bank, ICBC as well as many non-Chinese banks (e.g. World Bank, EBRD, IFC, EIB, ADB).

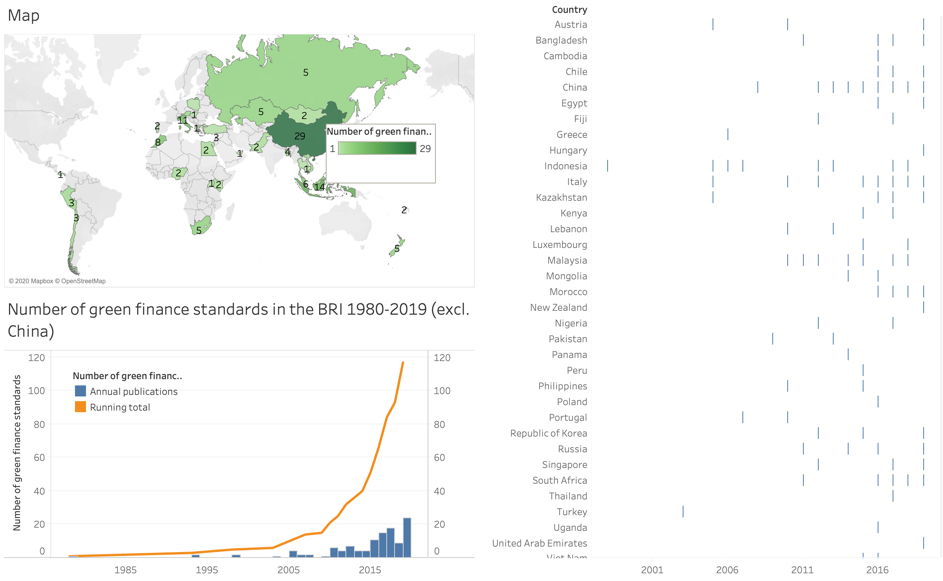

Since the BRI’s inception in 2013, the number of government-issued codes for green finance in BRI countries has grown from 36 to 117 in 2019. By 2019, more than 30 countries in the BRI had issued at least one green finance regulation, e.g. in regard to issuance of green finance instruments, reporting or use of proceeds. The leading country in regard to green finance regulations and instruments in the BRI is China, having issued about 30 guidelines over the past years.

Green bond issuances within the BRI

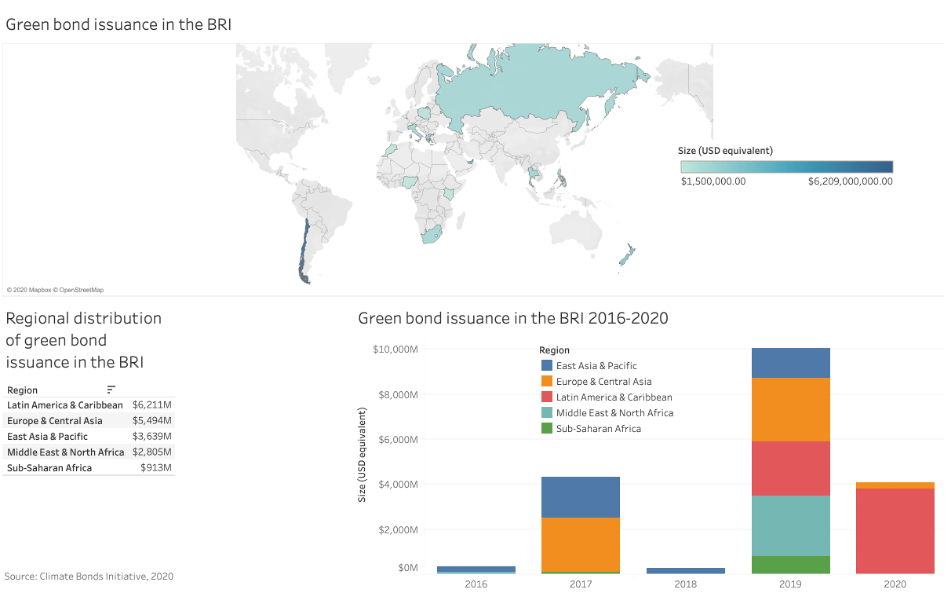

With the growth of green financial instruments, also the number of green finance deals has been increasing in the BRI. Over the past couple of years, green bond issuance have grown to up to 10 billion dollar (in 2019). Particularly issuers from Chile in Latin America have taken to the capital markets to raise green bonds, closely followed by issuers from European BRI countries (e.g. Italy, Poland), according to Climate Bonds Initiative.

When comparing the green bond market with the global green bond market developments, BRI countries (excluding China) accounted for about 20% of global green bond issuances. Similarly, BRI countries also accounted for 30% of global green finance regulations issued in 2019.

The use of green bonds, according to the prospects, is mostly for green transport, green buildings, as well as solar and water infrastructure, while particularly in the Southern BRI countries important issuers tend to be sovereign issuers (such as in the case of Chile).

Experiences from Chinese Green Urban Finance

Over the past 40 years, since the start of China’s economic Reform and Opening in 1979, China’s urban population increased from 170 million to 831 million in 2018 – with the Chinese urban population surpassing its rural population in 2011. With increased urbanization came adverse environmental consequences, such as air pollution, water pollution, changing weather patterns as well as high greenhouse gas emissions. With urban population on the rise, China has become the second most vulnerable country to climatic disasters, incurring more than USD 490 billion of economic losses as a result of climatic disasters in the period from 1998-2017.

To build resilient and eco-friendly cities, China required investments of around 7 trillion RMB for the year 2016-20 for the construction of greener buildings, large-scale retrofit of existing houses and commercial buildings (about 1.65 trillion RMB), transport infrastructure (about 4.5 trillion RMB) and energy infrastructure such as distributed photovoltaic (PV) (about 500 billion RMB).

To finance green urban development, apart from the direct development of a green finance system that allows acceleration of green urban finance, also a number of policies and initiatives that indirectly support an acceleration of investments in green urbanization, green transportation and green Industry 4.0 have been introduced on different levels of the Chinese regulatory system:

- A national carbon market, as called for in China’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), can promote green finance for cities by putting a price on carbon emissions; accordingly, money would be channeled in assets with lower climate impacts. While China designated seven carbon market pilot provinces and cities (Hubei, Guangdong, Shenzhen, Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing) already in 2011, unfortunately the development of the national (or sub-national) carbon markets has by September 2020 not seen the necessary progress.

- Construction of hundreds of “eco-cities” and “low-carbon cities” was pushed to highlight development potentials and channel money into green development at both the national and provincial level. For the period from 2016 to 2021, the total investment in constructing low-carbon cities in China is expected to reach RMB 6.6 trillion. Already in 2008, low-carbon city pilot projects began in Shanghai and Baoding. In 2011, 30 pilot cities for energy savings and emissions reduction were divided into three groups with RMB 600 million per year provided for provincial level cities, RMB 500 million per year for provincial capitals, and RMB 400 million per year for other cities. Cities receive 50% of the budget each year in advance and the remaining 50% according to the results of the annual performance evaluation. The funding in 2012 and 2013 was about RMB 4 billion each, RMB 5.3 billion in 2016 and about RMB 3.8 billion in 2018.

- National energy policy and energy saving policies for industrial, commercial and private users have been implemented.

Accordingly, projects that are supported by investment and financing of green urban and rural construction include:

- New green building projects. Green building is a life-saving period that saves resources, protects the environment, reduces pollution, and provides people with health, fitness, and efficiency. Use space to maximize the quality of buildings where people live in harmony with nature. The projects to be supported should be residential buildings, public buildings and industrial buildings, with reference to the “Green Building Evaluation Standard” GB/T 50378 two-star and above standards.

- Low-energy buildings and near-zero energy buildings. Low-energy buildings and near-zero energy buildings are focused on achieving low emissions and energy consumption. Focuses include enclosures, energy and equipment systems, lighting, intelligent control, and renewable energy utilization.

- Assembled construction projects. Prefabricated buildings where parts or all of the building is completed in a factory and the transported to the construction site. The building is assembled by means of reliable installation and installation machinery construction method. It is estimated that by 2025, the total investment will be about 1.03 trillion RMB, including the investment in full refurbishment, the investment in fixed assets of new parts and components, and the distribution of new parts and components.

- Urban drainage flood control project. The urban drainage flood control project mainly enhances urban comprehensive drainage, flood control capacity and water source conservation through the increase of drainage and storage space, new rainwater pipelines, large rainwater drainage corridors, machine drainage pumping stations, and emergency drainage facilities.

- Urban waste-water remediation project. The focus of black and odor water management includes: Source pollution control, non-point source pollution control, endogenous pollution control and other pollution (excessive standards for tail water in urban sewage plants, accidents from industrial enterprises, fall leaves, etc.).

- Urban sewage treatment quality improvement project. The urban sewage treatment quality improvement project includes new sewage pipe networks, old sewage pipe network reconstruction, combined pipe network transformation, new sewage treatment facilities, and sewage treatment facility upgrades.

- Urban water supply facilities renovation and construction projects. Urban water supply facilities’ renovation and construction projects include the transformation of urban secondary water supply facilities and the increase of county water use rates.

- Urban rail transit projects & Urban road facilities construction and renovation projects. Construction and renovation projects of urban rail and road facilities include the addition of urban roads, new bridges, as well as addressing the problems of partial damage, insufficient supply, and insufficient auxiliary facilities in the county road system.

- Construction projects for urban garbage disposal facilities. The construction of urban garbage disposal facilities includes the construction of urban domestic garbage disposal facilities and county garbage disposal facilities.

To further raise revenues and address green growth, China is experimenting with green taxes. The Environmental Protection Tax Law came into effect on 1st January 2018. It makes businesses and public institutions that discharge air, water, solid waste, and noise pollution to pay according taxes. The law replaces local pollutant discharge fees, of which the central government took a 10% cut. Now, all the tax income goes to city governments. The effectiveness and revenues of these taxes have yet to be studied.

Another important development for urban finance in transport, urbanization and industry 4.0 has been the recent expansion of real estate investment trusts (REITs) in China. At the end of April 2020, in the wake of the nCovid-19 pandemic, Chinese authorities (NDRC, CSRC) announced a pilot program for REITS in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region the Yangtze River Delta, the Xiongan economic zone, the Hong Kong Zhuhai Macao area and the Hainan Province. Through REITs, public participation in infrastructure projects can be accelerated, where REITs buyers own a share of the infrastructure. In the pilot, REITs can be issued for projects including logistics and warehouses, toll roads and transportation infrastructure, urban utilities, sewage and garbage processing, information networks and others in strategic and emerging industries.

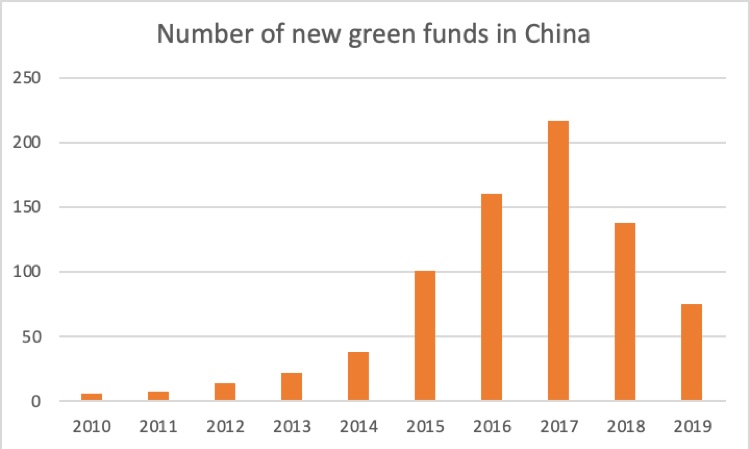

In January 2019, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment issued the “Opinions on Supporting the Green Development of Private Enterprises”, which proposed to accelerate the establishment of a national green development fund, to encourage local governments and social capital with conditions to jointly initiate regional green development funds, and support private enterprises.

In 2019 , there were 77 green funds established nationwide and filed with the China Securities Investment Fund Association , including 75 privately-funded green funds and 2 publicly-funded green funds (see Figure 1). In 2019, the funds were used for new energy (51%), biodiversity conservation (45%), circular economy (2%) and energy saving (2%).

Experiences from the European Union Green Urban Finance

The landscape of green urban finance in Europe is characterized by the interplay of the several different policy levels in the EU: public national funding meets EU structural and investment funds and private funding. Member States, private actors and the EU all play a role in financing green urban development. The EU has a growing regulatory framework in place to increase investments in the green finance sector.

In November 2018, the European Commission published the Long-Term Strategy (LTS) for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy. The vision, named “A Clean Planet for all”, formulates the goal of “achieving net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050”. The framework contributes to regulatory stability as a key element for public authorities and private actors to achieve the EU’s emission reduction targets. To complete the transition towards a net-zero greenhouse gas economy, the LTS states that “private business and households will be responsible for the vast majority of these investments. To foster such investment, it is crucial for the European Union and Member States to offer clear, long-term signals to guide investors, to avoid stranded assets, to raise sustainable finance and to direct it to clean innovation efforts most productively”. At the same time, the EU has designed and put in place several public structural and investment funds to boost green finance. They are administered by the European Commission in cooperation with the Member States.

A major development for green finance has been the announcement of the European Green Deal in December 2019. The Green Deal is the EU’s strategy for a sustainable economy, in which the EU formulates in more detail how to achieve the goal of net zero emissions of greenhouse gases in 2050. It describes the EU’s commitment to tackle climate-related challenges and the need for an economic transition towards a sustainable future. One of the key elements of the roadmap put forward in the European Green Deal is the financing of the measures and policies announced. There is a significant need for green finance and investments to achieve the ambition set by the Green Deal. Both public and private investment will have to be mobilized.

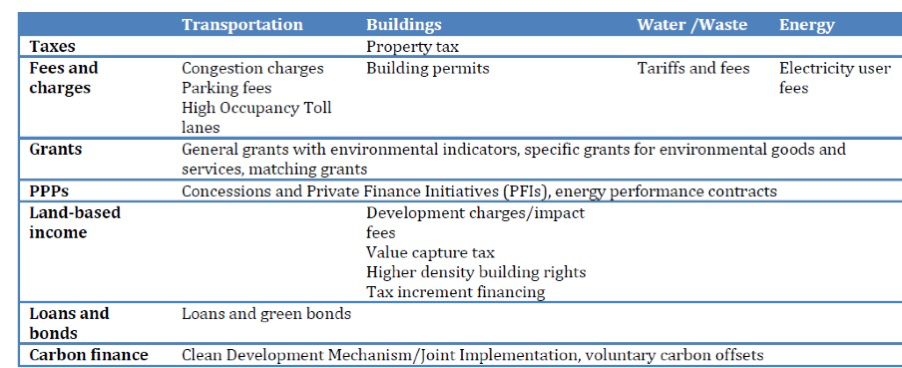

The greening of municipal financial instruments is an important first step towards achieving greener urban infrastructure. As cities have revenue sources that are tied to many aspects in all urban sectors, their design can stimulate or dissuade the development of greener and more sustainable cities (OECD 2012). According to OECD (2012) in some European countries (e.g. France, Netherlands, Norway and Sweden), capital expenditure in environmental protection is incurred almost entirely by the local government, in other countries (e.g. United Kingdom and Iceland), local government represent less than a third of total government expenditures in this sector. In decentralised countries, such as Spain or Belgium, regional government expenditures in environmental protection account for nearly a third of total environmental expenditure.

The table gives an overview on financial instruments in Green Urban Sectors, which have contributed to the greening of the urban financial landscape.

Attracting private funding is an essential prerequisite to meet the European Union’s 2030 and 2050 climate targets. Especially for the energy, buildings and transport sectors, an increase in investments is needed. The European Commission estimates that overall investment will need to grow to be between €176 billion and €290 billion per year higher than it would be under current policies (or €520 to 575 billion per year without calculating with the baseline)[6]. This translates to around 2.8% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) invested annually. Currently around 2% of GDP is invested to decarbonize the EU’s economy, as calculated by the Commission[7]. This investment opportunity – or gap – calls for a significant increase in green finance, notably from the private sector. To enable private funding, policy certainty and de-risking private investments will be key issues in delivering on agreed EU targets.

The gap and challenges of green finance in the BRI

Green urban finance in the BRI and countries investing in the BRI, such as China and European countries, is gaining momentum with stakeholders from regulators, financial institutions and non-governmental organizations accelerating providing regulatory guidance, tools and application examples.

Yet, when considering the multi-trillion USD overall need of providing green finance to the BRI countries, it becomes obvious that the current level of green finance is insufficient to address the financing gap for sustainable urban development. Neither cities nor private investors in the BRI are currently still able to sufficiently issue green finance instruments in most BRI countries. While some international private investors have tried to deal with this problem by issuing green BRI bonds (e.g. the Chinese ICBC in April 2019 issued the first green BRI bond worth approximately 2.2 billion USD in Singapore), green finance in practice in the BRI countries has more potential to develop.

While the current status of urban finance in the BRI is both insufficient in terms of providing sufficient liquidity and providing capacity to focus on green development, several initiatives (such as the BRIGC) are enabling investors, developers and local authorities to learn how to apply green urban finance and ideally scale it to other cities and sectors as well. The capacities that particularly development finance institutions are applying, should be harnessed more to provide local capacity, while “green” regulatory processes (e.g. for project planning and approval) in both the host country and the investor country should help steer finance into green projects.

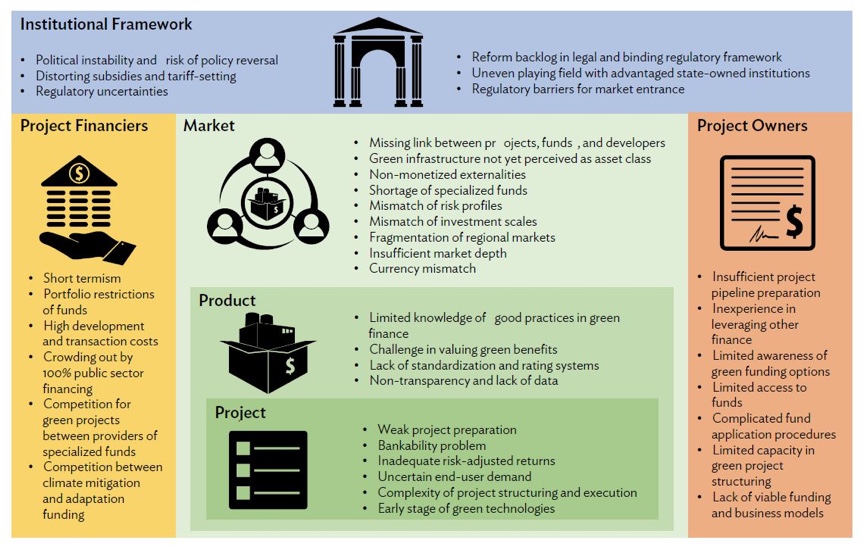

Yet, challenges for green urban finance that are relevant for Europe and China, are equally if not more relevant in the BRI. The following figure illustrates major categories of constraints for green finance that are relevant in Europe, China and the BRI.

In summary, the challenges are:

- Insufficient Institutional Framework, such as political instability and the risk of policy reversals (e.g. for subsidies);

- Insufficient project financiers with short-term financial goals compared to long-term investment needs and high transaction cost;

- Insufficient markets with missing links between projects, funds and developers;

- Insufficient product developers with lacking knowledge of good practices in green finance;

- Insufficient project development capacity and project bankability;

- Insufficient capacity of project owners, for example for applying leveraged or blended finance.

In addition to green finance market challenges, there are particular challenges that cities are facing:

- Development finance institutions are often working with national governments and not with cities. This makes the connection between the cities and the development finance institutions more difficult;

- Cities and national governments often speak “different” technical languages, making communication more difficult (e.g. many cities don’t have sufficient capacity; regarding environmental and green development). At the same time, cities only have a limited budget for consultants to prepare green projects in accordance with national or even international requirements;

- City governments are often elected (or appointed) for a period of 3-5 years, while green investments in urban infrastructure have a longer pay-off time and thus would have a different success period;

- Different time horizons from different investors requires particular financial structuring skills and good treasury management skills to structure financing according to financing availability, risks and returns.

While many of the challenges in regard to green urban finance that are relevant in China and Europe are also relevant in the BRI, additional challenges for green urban finance need to be dealt with in many of the BRI countries. These risks are more pronounced in smaller BRI countries, but are applicable to most emerging economies in the BRI:

- BRI countries often have less developed financial markets to raise green funds through the capital markets. This is particularly true for smaller BRI countries;

- BRI countries often have lower capacity to support technical reporting on green indicators relevant for green investors (e.g. environmental outcomes such as emissions);

- BRI countries often have insufficient tax base for public finance of larger green infrastructure projects (e.g. public urban transport);

- Several BRI countries are already struggling to service current debt making further fund raising for green projects particularly challenging;

- BRI countries often have insufficient planning and appraisal capacity to deal with the complexities of green urban planning for transport, urbanization and industry 4.0.;

- There are high currency risks for many BRI countries making investment in local currencies often difficult for investors, while raising funds in international currencies risks that issuers/borrowers (either governments or private institutions) are exposed to currency risks.

- Insufficient liquidity in the secondary market to increase investment potential into green projects or de-risking of investor portfolios.

Recommendations

The application of green urban finance instruments and the development of accompanying policies to invest in green transport, green urbanization and green industrialization has been developing significantly in Europe, in China and in the BRI countries.

Despite much progress in green urban finance, however, investments for urban development are continuing to be both insufficient and too often used for non-green development. While this lack of funding has been noted for years, the recent nCovid-19 pandemic has exacerbated that problem. To overcome the shortage and provide an accelerated deployment of green finance for green urbanization in the BRI, we developed 11 recommendations.

- Provide Green Urban Project Preparation Facilities

- Harmonize Green Finance Standards

- Improve Capacity of integrated planning for green urban development to lower financing cost

- Build a Sino-European green city fund

- Increase use of Blended finance

- Establish open platform for green urban projects

- Apply digital technologies for MRV

- Establish better platform for MRV data sharing

- Create and apply standards for reporting

- Provide open learning platform for best practice exchanges of policy and project design and implementation

- Improve green investment incentives in China and the EU for green overseas investment in BRI cities

Cooperating and political willingness to support green urban development in the BRI and elsewhere continues to be major accelerator for success. With current economic developments at the time of this writing in the first half of 2020 being challenging, green development continues to be not only a major necessity, but also a solid platform for negotiation, communication and cooperation.

In conclusion: Climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation and green urban growth in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is all but certain. There is, however, a good opportunity to drive green urban growth when investors, city planners and policy makers in Europe, China and in the countries of the BRI step up efforts to steer investments smartly into green projects.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.

Comments are closed.