In April 2019, the 2nd “Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation” will be held in Beijing with many heads of governments and business shaking hands and discussing opportunities of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Until then, critics and proponents of the Belt and Road Initiative will increasingly weigh in their opinions on advantages and risks of the Belt and Road Initiative, such as the Chinese newspaper China Daily titling on March 12, 2019 that the “BRI is hailed as a force for sustainable development”[1] or CNBC`s feature earlier this year that “Fears of excessive debt drive more countries to cut down their Belt and Road investments”[2].

Source: China Daily, March 12, 2019

Source: CNBC, January 17, 2019

As with most judgments, also the judgment on the success or failure of the BRI will depend on the perspectives taken. This article analyzes the potentials of BRI investments to leapfrog BRI economies into a green era. Particularly, it compares efforts of the Chinese Going Global strategy in the early 2000s that allowed many African countries to connect to mobile communication using Chinese technology to today’s potential of technologies in green transport and green energy.

China’s global investments in 2000s

The international community has been watching Chinese international ambitions much more closely since the Chinese President Xi Jinping labeled Chinese international investment and cooperation ambitions the “Belt and Road Initiative” in 2013. With a vision to develop infrastructure worth a cumulative $6 trillion across the some 100 BRI countries across 5 continents employing multilateral, bilateral government and private investments, this initiative is poised to impact about “40% of the earth`s total area, 30% of Global Gross Domestic Product, 55% of total CO2 emissions, and 60% of the world`s population”[3], mostly in less developed countries.

However, while the term Belt and Road Initiative is new, Chinese international investments, often with government support, have over the past 20 years been supporting economic development, particularly in less developed countries. With the Going Global strategy, China, for example through its China Development Bank (CDB) and China Export Import (Exim) Bank, invested often welcomed money in other emerging countries already in the early 2000s. One such fund was the China Africa Development Fund, which was established in 2007 with USD 1 billion from the CDB. To put Chinese ambitions of that time into perspective: According to research by the Financial Times, China Development Bank and Exim Bank lent “at least $110 bn to governments and firms in developing countries in 2009 and 2010”. This compares to “only” $100 bn of World Bank loans between mid-2008 and mid-2010.[4]

These Chinese driven investments not only built cement factories, roads and energy networks since the early 2000s, but also helped millions of people in Africa: in 2010, the then little known Chinese technology companies ZTE and Huawei provided communications services to 300 million African users in 50 African countries, in a previously underserved continent in terms of communication. By bundling cheaper prices, better services and financing, the Chinese players could outcompete classic telecoms providers such as Ericsson, Siemens and Nokia.[5] The Chinese investments not only helped these countries to leapfrog to modern communication technologies, but aided the spread of mobile payments, enabling small businesses and rural connectivity and contributing directly and indirectly to the economic growth in many countries.

Investments in the Belt and Road Initiative – can it make the BRI leapfrog to green

When analyzing BRI investments today, much emphasis is put either on the investments of Chinese State Owned Enterprises (SOEs) or State-linked Enterprises in high-technology (e.g. Midea’s buy-out of German robotics company Kuka in 2016), classic infrastructure projects (e.g. China General Nuclear Power Cooperation (CGNPC) investing in British nuclear energy, or China Ocean Shipping Company investing in the Piraeus harbor in Greece – both in 2016). On the African continent, much reporting emphasis is put on construction projects (e.g. of roads or rails connecting mines and ports) financed by Chinese loans.

However, similarly to the leapfrogging opportunities that mobile telecommunication technology provided in the early 2000s in many African countries, technology, including Chinese technology, today can support green development in BRI countries by leapfrogging from an undersupply of energy, transportation and ICT to create smart cities, renewable energy generation, low-carbon transport and digital services.

Among the Chinese companies, that have over the past years become technology leaders and continue to push the technological frontier in their respective fields, should be counted:

- Transportation technologies,

e.g.

- Didi in shared and hailed mobility

- BYD in new energy vehicles, such as electric buses, trucks and cars

- Alibaba in traffic management

- China Railroad Rolling Stock Corp in subway systems

- CRRC in high-speed public transportation

- Green energy

- Goldwind and United Power in wind turbines

- Trina Solar, Yingli Solar in solar energy

- Alibaba in smart cities and energy management

- Jiangsu Linyang Electronics in smart meters

- BYD and Huawei in energy storage and management

- Digital infrastructure

- Alibaba and Tencent in digital and mobile payments

- Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent in artificial intelligence

- Huawei, ZTE in 5G communications networks

Contrary to the perception that state-owned enterprises in China are often in the driver’s seat, it particularly private Chinese companies that contribute to innovation and private investors who contribute to the spread of new technologies – also along the BRI: a recent World Resources Institute (WRI) study analyzing investments in BRI countries showed that “nearly two-thirds (64%) of cross-border energy-sector investments by Chinese privately owned enterprises (POEs) were in renewable energy”[6], while most money from state investors and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) went into more traditional industries.

Green Investment in green innovation – an opportunity for combating climate change…if done right

The speed of implementation of innovation and the cooperation of the different layers of the business and political ecosystem to implement Chinese innovation have sparked political resistance from some in the international community: for example, Western leaders are discussing the risks of installing Huawei`s 5G telecommunications technology or European cities have been hesitant to purchase electric buses from Chinese manufacturer BYD as a means to lower emissions in public transportation.

But, in order to fulfill the commitments to combat climate change, as most of the world`s countries (including the PR China) have agreed to in the Paris Agreement, and in achieving the UN`s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the world must invest in new and upgraded technologies with no CO2 emission, lower ecological footprints AND enable economic prosperity, particularly in currently less developed economies and particularly in the areas with some of the heaviest ecological footprint: energy and transportation.

Green energy

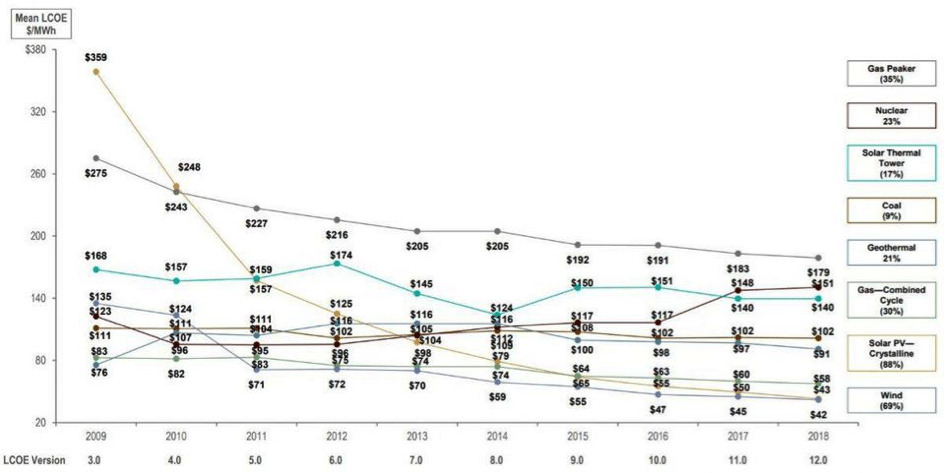

Thanks to big advances in technology, creating energy in a low or zero emission fashion seems more achievable than ever before: while investments in green technology seemed more expensive compared to traditional energy in earlier studies (e.g. 2012 IEA and World Bank studies claiming that employing green technology to close the infrastructure gap in BRI countries would require an additional USD 80 billion compared to brown investment[7]), technological developments have made greener cheaper. As a 2019 study by the think tank Lazard showed: annualized levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for solar photovoltaic and wind energy have dropped by 88% and 69% respectively from 2009 to 2018, while LCOE for coal and nuclear have increased by 9% and 23% respectively (see Figure 1).[8] With further falling of prices expected for both renewable energy generation and storage, investments in brown energy become ever less lucrative than their green alternatives, and with the right policies they become prohibitively expensive.

With other words, savvy investors and governments interested in affordable energy will all but avoid investing in traditional energy, as the costs over the short term will be higher than their green alternatives. Investing now in new coal or gas-fired power plants is nothing short of a brown trap.

Green transport

Similar to rapid technological advancements in the energy sector, the transport sector is undergoing a technological revolution. Electric mobility, digitalization, connectivity and increased automation will not only change the way people and goods are transported, but how many emissions will be created. The investments in transportation infrastructure today will therefore not only determine the accessibility of mobility for the people, but their impact on our environment.

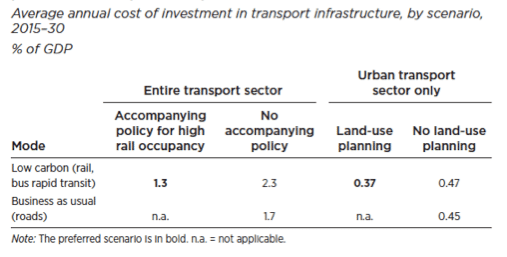

According to multiple studies, greening the transportation sector, at this point in time, will still require more investments compared to investment in purely transportation without greening it. To lower cost, investors and policy makers should particularly emphasize on capacity building of regulators: According to a recent World Bank study, the necessary investment in green transport depends strongly on accompanying policies, such as land-use planning, public transportation use etc. With accompanying policies, investments in green transport to fill the transportation gap is only 1.3% of GDP in emerging markets, as compared to 2.3% without accompanying policies for the entire transport sector, and 0.37% compared to 0.47% in the urban transport sector (see Figure 2). This is still a massive investment gap, requiring international investors to cooperate and coordinate with multilateral and bilateral development banks as well as technology providers, operators and policy makers that need to create the necessary frameworks and incentives.

The focus of the support policies (and with it investment) should include:

- support the use of electric buses, instead of diesel buses,

- build electric mobility charging infrastructure to increase spread of electric mobility;

- strengthen interconnectivity of vehicles to allow increasing autonomy of cars to improve safety and efficiency;

- create incentives for resource sharing in freight and passenger transport (e.g. shared freight hubs, shared bike-services)

As many of these policies that involve new technologies in transport are still being tried out in many countries with varying degrees of success, international exchanges and cooperation are paramount to avoid repetition of ecologically harmful mistakes, as the cases of Chinese bike-sharing operator ofo or failed public transport networks have shown.

Outlook – seize the green technological opportunity

Seizing the Green Belt and Road Initiative and

making it ecologically sustainable through green technology is a unique

opportunity for the involved countries – both in terms of creating economic opportunities

and to avoid the brown technology trap. Involved stakeholders should embrace international

cooperation on financing, experience sharing and capacity building, that

includes international consensus on green and sustainable finance, an emphasis

on local differences, and the credibility of institutions and policies that

monitor, evaluate and punish relevant companies in non-compliance. Some of the

institutions are in place or are being implemented (e.g. green financing

standards), much of it still requires international negotiations and agreements

(e.g. monitoring and enforcement mechanisms). The success will be decisive for

the sustainable development of all involved countries.

[1] Cao, “BRI Hailed as Force for Sustainable Development.”

[2] “Debt Fears Drive Countries to Cut Belt and Road Investments with China.”

[3] United Nations Environment, “Green Belt and Road Strategy.”

[4] Chris Hogg, “China Lends More than World Bank,” BBC News, January 18, 2011, sec. Asia-Pacific, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-12212936.

[5] Marshall, “China`s Mighty Telecom Footprint in Africa.”

[6] Zhou et al., “Moving the Green Belt and Road Initiative: From Words to Actions.”

[7] Ma et al., “Greening the Belt and Road.”; La Rocca, Green Infrastructure Finance.

[8] Mahajan, “Plunging Prices Mean Building New Renewable Energy Is Cheaper Than Running Existing Coal.”

[9] Lazard, “Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis – Version 12.0.”

[10] Rozenberg and Fay, Beyond the Gap.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.

Comments are closed.