On the surface, the global community agrees: We need sustainable development – for the benefit of all. However, in practice, the devil lies in the details – and in different priorities of nations and organizations in trying to achieve the triple bottom line: economic growth, social development, and ecological protection.

Over the last 2 weeks, I was invited to contribute to three conferences in China on financing sustainable innovation. During these conferences, I experienced once again how Chinese and European colleagues agree on the surface about the need for sustainable development, but not in practice on the actions to take. These differences reflect the divergent needs and views of different nations, as well as the complexity of sustainability across the world. But with billions (RMB, EUR, USD, Yen,…) invested in the name of sustainable development, for example in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), I believe that these differences in understanding of sustainable development will lead to contradictions, disagreements and suboptimal results if not managed properly.

In this article, I dare not to offer a solution – nor do I want to say that anyone is right or wrong. But I will provide tendencies of past investment patterns for sustainable development looking at data from China and Germany, provide a quick view on the current (and partly alarming) state of sustainable development, and share my observations on the differences in the preferred actions to sustainable development that became evident while working with European and Chinese experts at the conferences.

Sustainable development – we agree, maybe.

It seems there is a universal agreement that the world needs sustainable development. At Belt and Road Initiative conferences, international cooperation conferences, innovation conferences, all talk is about the need for sustainable development.

The global understanding and commitment to invest in sustainable development is decades old. Already in 1987, the United Nations in the Brundtland Report emphasized the integration of the “triple bottom line” of economic, social and ecological development. In 2015, the World agreed to focus multilateral sustainable development activity on 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (see Figure 1) until 2030.

Figure 1: United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

As a consequence, many countries have been investing in all types of assets and activities to support sustainable development, at home and abroad, taking responsibility for themselves and others.

In doing so, countries employ vastly different strategies. When looking at data for overseas investment activities over the last years by, for example China and Germany, significant differences in investment priorities emerge. China emphasizes infrastructure and industrial investment as drivers for economic development to achieve social well-being and then environmental protection, while countries like Germany focus on capacity building with a stronger focus on environmental and humanitarian/stability to achieve well-being.

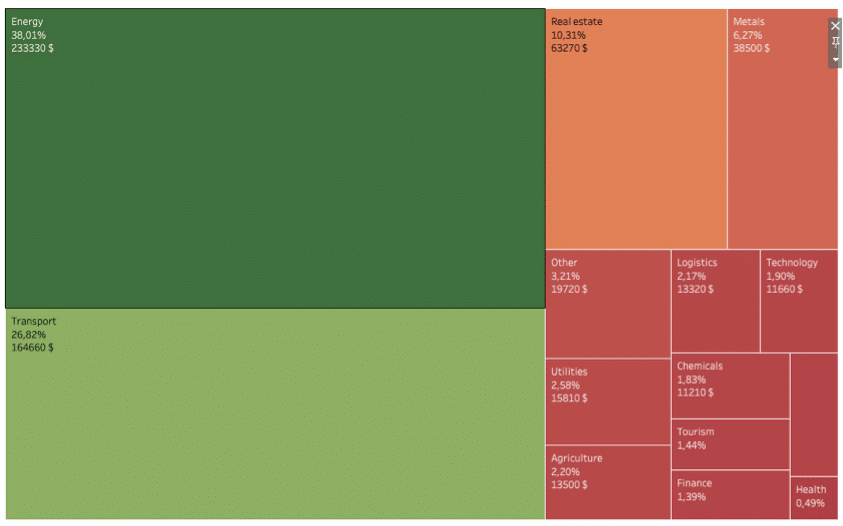

Within its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China, aims to “help developing countries break bottlenecks to development (…) and benefit from global value, industrial and supply chains”, emphasized Chinese President Xi Jinping [1]. In other words, by investing in infrastructure connectivity (e.g. transportation, energy, ICT) (SDG 7 and 9) to allow for more industrial production and trading (SDG 8), people will move out of poverty (SDG 1), have enough money to buy food (SDG 2). In practice, China has invested more than 600 billion USD in BRI countries over the past 15 years, particularly in energy and transport infrastructure (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sum of Chinese investment in BRI countries in different industries, 2005-2018 [2]

The BRI aims to support sustainable development, and incorporates economic, social and environmental considerations into its investment. For example, green development was again emphasized at the last Belt and Road Forum in 2019, where some 20 banks signed the Belt and Road Green Investment Principles (GIP) and the Joint Communique of the Leader’s roundtable includes many references to green finance and green development as well as fighting corruption. In practice, however, China adheres to the host country principle. That means that local laws need to be followed, and the local governments have the right to decide on all matters of the project within the local laws – while global norms and standards are secondary. As a result, if a local government wants to build coal-fired or solar power plants, China will support either.

Other countries follow a different approach of sustainable development. The German government, for example, invested about 25 billion USD in sustainable development in third countries (in overseas direct assistance – ODA) in 2018 [3]. Contrary to China, Germany invests almost as much in technical assistance projects as it invests in financial assistance projects – arguably with two priorities:

1. Build sustainable living and working conditions in emerging economies by providing capacity building for employability, security, rule of law, press freedom, e.g. to stop the flow of refugees.

2. Ensure environmental protection, particularly climate change and biodiversity through project and governance work.

Also, contrary to the Chinese approach, the German (and European) approach for sustainable development through public money is bound to conditionality – it requires certain safeguards for sustainability (e.g. equality, environmental protection) that often go beyond local laws. That means, for example, that The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) will not finance coal fired power plants any more to support the Paris Accord.[4]

A lot of talk and too little action?

With so much money being invested for sustainable development in emerging economies, including BRI countries, are we succeeding in sustainable development – that is in terms of economic, social and environmental progress? The short answer is – yes, but no.

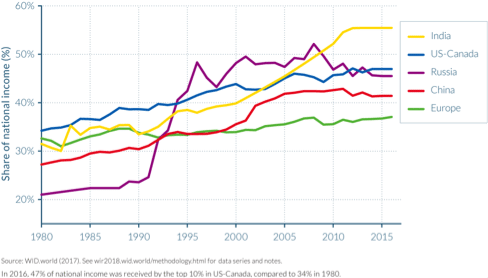

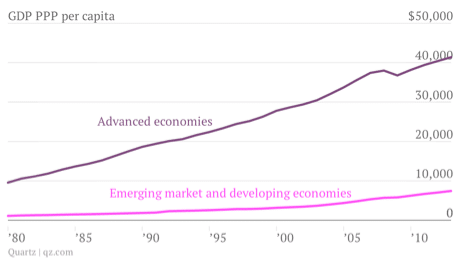

On the economic front, most countries have increased their GDP and the World grew monetary wealth by an average of 3.5% over the past 40 years – making the World 4 times “richer” today than in 1977 (SDG 8). Many countries have moved from emerging to middle-income country status (such as China that increased its GDP by 64 times in 40 years), or to developed country status (such as South Korea that increased its GDP by 40 times in 40 years). This has lifted billions of people out of poverty to reduce the share of people in the world living below USD 1,90 a day from 36% in 1990 to 10% in 2015. However, while many people profited from this development, data show that the disparity between the rich and poor people within a country (see Figure 3) and the disparity between rich and poor countries (see Figure 4) is on the rise almost everywhere, leading to rising inequalities (SDG 1, SDG 10).

Figure 3: Top 10% income shares across the world, 1980-2016: Rising inequality almost everywhere, but at different speeds

Figure 4: Development of GDP per capita in advanced and emerging/developing economies 1980-2012

Advanced economies are, according to the IMF, the 34 nations that result from combining the members of the G7, EUR area countries, and the 4 “newly industrialized Asian economic areas” – Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea. The world’s 150 other nations are considered emerging or developing [5].

On social sustainability, to name but two examples, global health improvements have led to an increasing lifespan of 8 years over the past 40 years (SDG 3). At the same time, however, wars and conflicts have uprooted more than 68.5 million people in 2017 – more than ever before[6] (SDG 16).

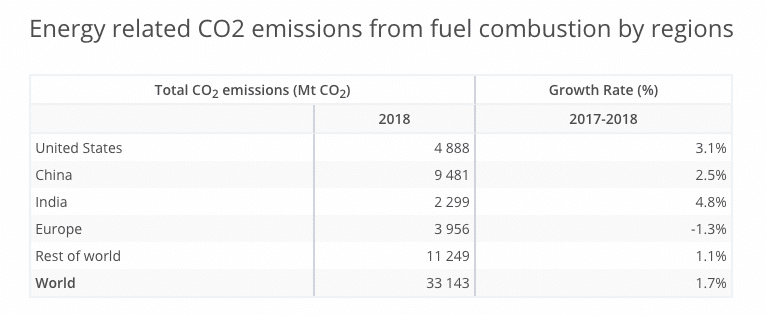

On environmental sustainability, the dangers of loss of biodiversity and climate change are ever more alarming. In 2018, global energy-related greenhouse gas emissions rose to a historic high of 33.1 Gt of CO2-equivalent (see Figure 5)[7], driven by energy use, transportation requirements, agriculture etc.

Figure 5: Energy related CO2 emissions from fuel combustion[8]

The increasing CO2 concentration in the atmosphere has led to an increase of global temperatures by 0.7 degrees Celsius in only 38 years. As a consequence, desertification threatens more than 1 billion people[9], extreme weathers costs lives, livelihoods and destruction of economic goods worth almost 150 billion per year[10], and in 2019 the Arctic Sea Ice Extent has reached its lowest thickness ever measured in the month of April.

In addition, “The health of ecosystems on which we and all other species depend is deteriorating more rapidly than ever” with human activity accelerating loss of biodiversity by tens to hundreds of times, threatening up to 1 million species within decades, according to the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the UN framework that assesses biodiversity.[11]

Setting next priorities for sustainable development – listening to the experts

What needs to be done to accelerate sustainable development then? Where should the priorities be in terms for example of financing?

I took the opportunity to explore this question in two sessions that I was invited to support at these conferences.

Application of smart technology vs. smart application of technology

The first conference was the 2019 EU-China Forum on Urban Scientific Research and Innovative Industry Development in Tianjin on May 17th, organized by the China Center for Urban Development (CCUD). It brought about 1,000 experts to Tianjin to discuss how to apply innovation and technology for sustainable development, e.g. in smart cities.

During the discussion and presentations, differences in priorities between Chinese and European participants became evident: Most Chinese experts focused on the application of smart infrastructure and technologies, while most European experts focused on the smart application of planning and technology.

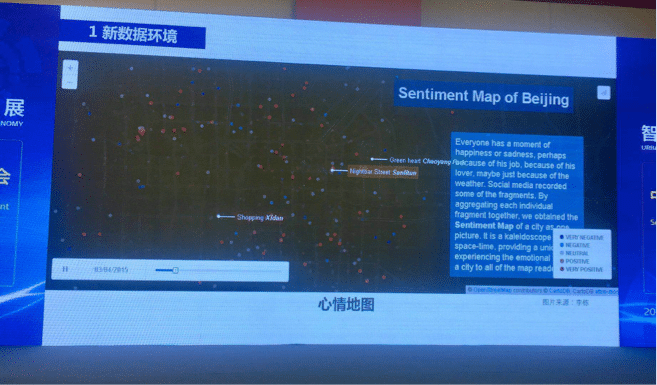

On the Chinese side, examples included the application of artificial intelligence to analyze big data from smart phone usage patterns to better understand sentiments of a city (see Figure 6). Mao Mingrui from Urban XYZ, for instance, introduced how the use of data that analyzes when and where people take and share pictures on public platforms allows us to improve tourism experiences; how the analysis of when, where and what mood people share through the use of stickers/emoticons in chat-apps on public digital allows us to understand their sentiment; and how the analysis of what modes of transportation people use under which circumstances allows us to improve city planning. Yan Jun, Chairman of Alpark in his keynote presented how the analysis of video data from camera technologies will improve not only traffic management, but public safety (i.e. seeing who committed a crime). The idea is that by using technology, policy makers are better informed, can make better decisions and thus improve resource allocation. In the end, this will lead to a prosperous and safe city.

Figure 6: Application of Big Data to analyze people’s sentiments in Beijing[12]

In contrast, European participants focused on the smart application of new and old technologies for the goal of adapting to current times. Rhys Whalley from the Manchester-China Forum and Amit Prothi, from the Rockefeller 100 Resilient Cities Project showcased the change of different cities such as Manchester and Amsterdam from old industrial towns to modern towns. They focused their presentation on the possibilities of integrating the cities’ old industrial histories (e.g. out-of-operation factories) that formed the character and culture of the city, while the smart redesign and application of technologies allowed the cities to move to modern times (e.g. moving media cities into old industrial complexes). These experts believe that focusing on smart, that is selective application of innovation (both technology and non-technological innovations, such as increased walkability of cities) into existing structures will create a more sustainable city that saves resources and provides better opportunities.

Using natural resources for sustainable development vs. protecting natural resources for sustainable development

A similar difference in the Chinese and European approaches to sustainable development emerged at the Annual Meeting of the Chinese-German Future Bridge Alumni in the Sino-German Eco-Park in Qingdao on May 24-26. The Future Bridge (“Zukunftsbrücke”) is organized by the German Mercator Foundation, the German BMW Foundation and the Chinese All China Youth Federation (ACYF) since 2011 and has about 400 members, all leading professionals from China and Germany.

During a three-hour workshop, I invited the Chinese and German participants to discuss what sustainability means to them and how China and Germany can support sustainable development in third countries. The verdict was clear: An overwhelming majority of Chinese participants agreed that a focus on SDG 8 (economic development) and SDG 9 (infrastructure) will help us achieve SDGs 1 and 2 (no poverty/ no hunger) in China and abroad – and thus sustainable development. The argument was that in order to help people move out of poverty, we need more infrastructure and economic development. Social concerns, such as gender equality (SDG 5) also played a role for Chinese participants, while environmental concerns (SDGs 13, 14, 15) were of secondary importance. In contrast to that, the German participants focused on social (SDG 1, 4) and environmental sustainability issues (SDGs 13, 14, 15) as well as responsible consumption (SDG 12) to drive sustainable development (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: SDG Priorities of Chinese and German participants of the Zukunftsbrücke meeting 2019

In consequence, a lively discussion emerged between German and Chinese participants whether a focus on strengthening economic development would lead to more sustainability problems than solutions – with the majority of Germans believing it would and the majority of Chinese believing it would not.

The contrast of views became also evident when illustrating views with specific examples: Participants discussed the sustainability of the Chinese South-North Water Transfer Project (南水北调工程). The engineering masterpiece ultimately pumps 44.8 billion cubic meters of water annually (that is about 1,5 million liters per second) from the Southern Yangtze River 1,200 kilometers north to the 80 million people living in the arid Beijing area. Some participants argued that this project is a sustainability solution as it allows for more economic development and water safety in the Beijing region, while others argued that it creates sustainability problems, as it impacts the eco-system and fisheries of Southern China.

The practical implications and challenges for international sustainability cooperation and financing

What analyzing past data on “sustainable” development investments and these events made clear to me again, is that while the norm of “sustainable development” might be supported by all, its form is different for different people – reflecting the complexity of sustainable development.

Thinking about how to make use of these differences, an old Chinese saying came to my mind: “Give a man fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man how to fish, and you feed him for a lifetime.” (授人以鱼不如授人以渔). However, the saying seems to lack an important element for today’s development: a fisher needs a net, a boat, markets – that is infrastructure.

Over the past years, the two regions – China and Europe – have developed a unique and evolving set of capabilities for development. China currently possesses capacities, knowledge and financing means to build infrastructure quickly and affordably under many circumstances. Nowadays, Europe focuses its development efforts more on processes (such as complex environmental analyses) and capacity building.

Ideally, we would use these strengths to help “teach to fish”, finance and provide the infrastructure that allows to sell the fish, and ensure that people can choose to fish not only today, but in the future.

But this is easier said than done. With more players on the market for “sustainable development”, more money invested and different interests in competition, the challenge how to align our sustainable development efforts in detail will not become easier. In the discussions with the conference participants, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) proved – again – to be a powerful tool to find a common language and highlight differences in approaches of sustainable development. Yet in practice, we must become better in clearly expressing and justifying our actions for sustainable development, because when Chinese and European colleagues talk about “sustainable development”, they might mean very different things.

Postface:

I want to thank the China Center for Urban Development (CCUD) and the Organizers and Alumni of the Zukunftsbrücke (BMW Foundation, Mercator Foundation, All China Youth Federation) for giving me the possibility to arrange and experience such candid discussions. The views expressed in this article are not the views of these organizations, nor that of the IIGF.

[1] “Remarks by H.E. Xi Jinping President of the People’s Republic of China At the Press Conference of The Second Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation,” April 27, 2019, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/zxxx_662805/t1659452.shtml.

[2] Data source: Scissors Derek, “China Global Investment Tracker 2018,” China Global Investment Tracker (Washington: American Enterprise Institute, January 2019), http://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.

[3] Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung BMZ, “Entwicklung der bi- und multilateralen Netto-ODA 2012-2017,” Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung, January 14, 2019, http://www.bmz.de/de/ministerium/zahlen_fakten/oda/leistungen/entwicklung_2012_2017/index.html.

[4] Vanora Bennett, “EBRD Puts Decarbonisation at Centre of New Energy Sector Strategy,” European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, December 12, 2018, //www.ebrd.com/news/2018/ebrd-puts-decarbonisation-at-centre-of-new-energy-sector-strategy.html.

[5] David Yanofsky, “For the First Time, the Combined GDP of Poor Nations Is Greater than the Rich Ones,” Quartz, August 28, 2013, https://qz.com/119081/for-the-first-time-the-combined-gdp-of-poor-nations-is-greater-than-the-rich-ones/.

[6] https://www.unrefugees.org/refugee-facts/statistics/

[7] International Energy Agency (IEA), “Global Energy & CO2 Status Report – The Latest Trends in Energy and Emissions in 2018” (International Energy Agency (IEA), April 2019), https://www.iea.org/geco/emissions/.

[8] International Energy Agency (IEA).

[9] United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, “UN Reveals ‘The Forgotten Billion’ | UNCCD,” October 18, 2011, https://www.unccd.int/news-events/un-reveals-forgotten-billion.

[10] “Narrow-Minded – Insurance in Asia,” The Economist, June 11, 2015, https://www.economist.com/leaders/2015/06/11/narrow-minded.

[11] United Nations, “UN Report: Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating,’” United Nations Sustainable Development (blog), May 6, 2019, https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/05/nature-decline-unprecedented-report.

[12] Presentation by Mao Mingrui, Founder Urban XYZ, 2019 EU-China Forum on Urban Scientific Research and Innovative Industry Development.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.

Comments are closed.