Highlights

- Between 2014 and 2020, about USD160 billion of Chinese-backed coal-fired power plants were being planned or announced outside of China;

- More than USD65 billion of Chinese-backed coal-fired power plants have been either shelved, mothballed or cancelled since 2014, with more projects seeing delays in construction;

- In 2019 and 2020, Chinese backed coal-fired power plants worth USD22 billion and USD25 billion respectively have changed status to become either cancelled, mothballed or shelved;

- Since 2015, 23 Chinese-backed coal-fired plants were shelved and a further 14 were cancelled, while 20 new Chinese-backed coal-fired power plants went into operation;

- Of the 52 Chinese-backed coal-fired power projects announced since 2014, only 1 has gone into operation;

- No new Chinese-backed coal-fired power plant was announced in 2020; in contrast, new coal-fired projects in 2020 were announced with backing by India’s Adani group in India, by Korea and Thailand in Vietnam’s Sekong Power Station, and by Korea in Indonesia;

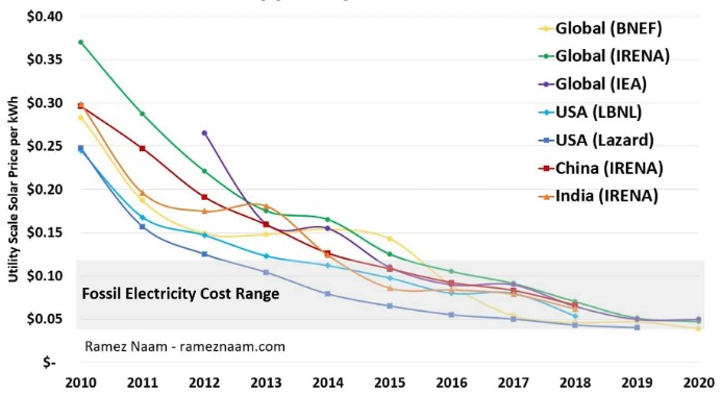

- The coal-exit is likely driven by increasing competitiveness for solar- and wind-power: solar-power costs have dropped by 80% in 10 years;

- At the same time, financing cost for coal-fired power plants have increased by 38% compared to 10 years ago, while 64 carbon pricing initiatives around the world make coal-financing ever less competitive;

- Recent biddings show that the price of electricity from new coal-fired power stations is about 500% more than from new solar-power plants;

- Multiple BRI countries (e.g., Pakistan, Bangladesh) have announced to phase-out new coal investments;

- In May 2021, G7 countries announced a stop to public funding for overseas coal financing;

- These developments open unprecedented opportunities and financial fire-power to accelerate a green energy transition in the BRI.

Coal-fired power plants in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)

China is considered the largest financier of overseas coal for the past years. As coal-combustion contributes to over 40% of global energy-related emissions, coal-related investments have come under scrutiny with many countries announcing to phase out coal investments in order to protect the world from a climate catastrophe.

To reduce its impact, relevant Chinese institutions have been engaged in re-evaluating investments in overseas coal fired power plants in cooperation with international partners. In December 2020, the BRI Green Development Coalition (BRIGC) under the Ministry of Ecology and Environment put all coal-related investments on a “restricted” project list through the Traffic Light System.

With the global tide turning ever faster against coal investments, numerous coal-related investments had come under scrutiny and were delayed or cancelled, while other coal-plant investments were mothballed during construction. Among the most prominent examples are:

- Kenya’s Lamu coal fired power plant, which was mothballed in 2019 due to large protests and a legal ruling that found insufficiencies in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) License – many months after construction had started. ICBC, which had originally agreed to finance the USD1.2 billion project, pulled back from the funding;

- Egypt’s Hamarawein 6.6GW coal-fired power plant was cancelled in February 2020. Of the USD4.4 billion, USD3.7 billion would have come from China Development Bank (CDB). Egypt proposed to invest in renewable energies instead;

- Bangladesh announced in November 2020 that it would not want to continue building some of its coal-fired power plants and requested the Chinese partners to shift this funding to renewable energy sources.

To further reduce coal-investments overseas, the countries of the G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK and US) announced in May 2021 to end public support for overseas coal financing by the end of 2021. This came after several of the G7 countries had announced individually to end coal-financing over the past years.

To understand the broader implications of this trend and what it means particularly for the financial institutions, this brief analyzes the developments of overseas coal power investments in the BRI and with Chinese participation with a focus on cancelled or otherwise halted construction of such plants. It also analyzes relevant financial reasons that drive the shift away from coal and the shift towards green energy.

China’s overseas power-sector investments

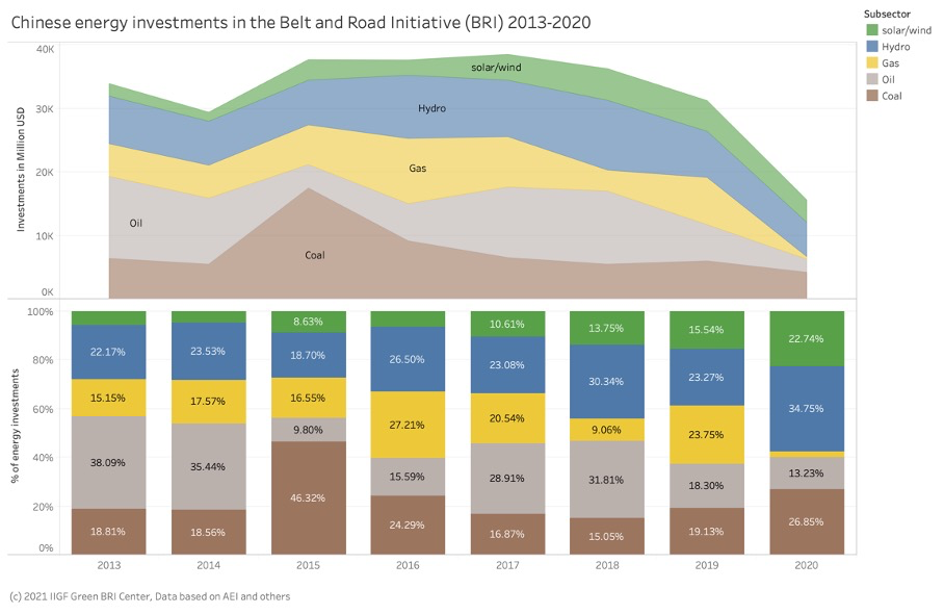

Chinese institutions have been providing financing and technology to build electric power generation facilities for decades, increasingly in renewable energies: in 2020 the majority of China’s energy investments were in renewable energies (see Figure 1).

However, when analyzing the state of coal-fired power plants announced or under construction, data show that many of Chinese overseas coal investments have been stopped, with possibly more coal-fired power plant under construction being delayed and cancelled.

A rapid phase out of coal-fired power plants with Chinese investors

To understand the trends of coal-fired power plants with Chinese financing and relevant financial risks, the following sections analyze a dataset on coal-fired power plants compiled by the Global Energy Monitor and enriched by the IIGF Green BRI Center.

About the data – Global Energy Monitor

The data used for the analysis are publicly available data from the Global Energy Monitor (GEM) and the GEM Wiki. GEM seeks to make reliable energy data available to allow studies about the evolving international energy landscape. All data used in the GEM is attributed to the original source, enabling users to identify the sources of the information.

The dataset lists about 13,000 coal plants and about 150 different coal fired power plant investments with Chinese participation outside of China. The datasets specify investors, development status over time and the power generation capacity, among several other information. GEM is a project funded by charitable donations from foundations and individuals, including the Energy Foundation, European Climate Foundation, GIZ, and KR Foundation.

About half of Chinese-backed coal-fired power plants shelved

Between the second half of 2014 and the end of 2020, 52 coal-fired power projects with Chinese financial participation outside of China had been announced. Of these announced projects, only 1 has gone into operation: the 1.3 GW Payra Patuakhali coal power station in Kalapara, Bangladesh, in the first half of 2020. At the same time, 25 of the projects announced since 2014 had been shelved and 8 ended up cancelled (see first data row of Table 1).

Several coal-fired projects had been announced prior to 2014 and accordingly 40 coal-fired power plants with Chinese participation were in the pre-approval phase between 2014 and 2020 (see second data row of Table 1), of which 4 went into operation, 9 were shelved and 5 were fully cancelled. For the 34 coal-fired power plant projects that had been under construction since 2014, only 19 went into operation, while 4 had been shelved. Of the 32 shelved projects since 2014, 9 were cancelled altogether.

Looking at the development between 2015 and 2020 (see Figure 2), coal investments moving forward (that is coal-fired projects, whose status has changed to announced, permitted, started construction or going into operation) saw their peak in 2015 and 2016. By 2020, the number of projects moving forward was reduced to less than USD2 billion. At the same time, the value of projects moving backward, that is projects whose status changed to cancelled, mothballed or shelved, increased from about USD2 billion in 2015 to about USD22 billion in 2019 and USD25 billion in 2020 (which equals about 23 GW of power). By 2020, coal-fired power projects worth less than USD1 billion went into construction, while no new coal-fired power plants with Chinese financing were announced.

Affected regions and countries

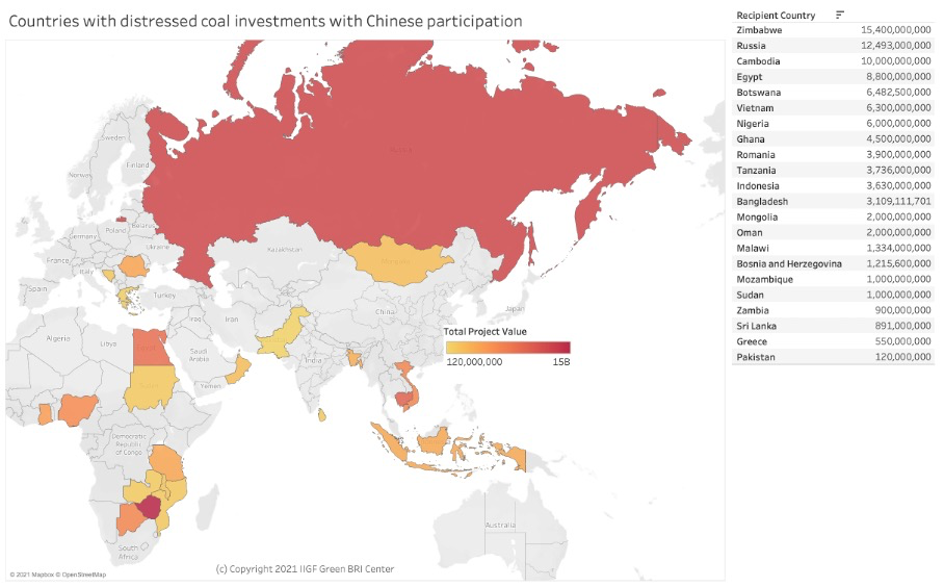

Several countries have been particularly affected by coal-fired powerplants being mothballed, shelved or otherwise cancelled: most importantly, Zimbabwe had announced multiple projects (e.g. Lusulu 2,3 and 4, as well as the 1.2 GW Gwayi Shanghai Coal Plant) that had been either shelved or cancelled over the past years – with a total value of about USD15 billion. A close second is Russia, where about USD12.5 billion of projects had been either shelved or cancelled (see Figure 3).

Affected Chinese investors

Multiple Chinese companies have been affected by projects being reversed. The exact values are hard to establish as not all financing arrangements are publicly available. Among the companies most affected by distressed projects are China Datang, which had been engaged in distressed projects worth USD10 billion (China Datang would not be the sole investor in these projects) and Power China, which had been engaged in distressed projects with a value of USD13.4 billion. In comparison, ICBC was involved in distressed projects worth about USD5 billion.

While it is not clear how much money had been spent for each project before it became distressed, a possible estimate is that a minimum of 5-10% had been spent on legal and due diligence cost to get the project off the ground. This would equal to a USD4-8 billion loss, particularly in the years 2019 and 2020.

Financial reasons for reduced coal-investment in the BRI

To understand the acceleration in reducing coal-fired power plants investments, it is important to understand three interrelated financial reasons:

- Rising cost of financing for coal-fired power plants

- Increasing risk for investors, particularly carbon price risks

- Improving competitiveness through decreasing cost of alternative sources of energy, particularly solar and wind

Cost of financing

With increasing understanding of climate-related financial risks for high-emitting assets, financing costs for coal-fired power plants have increased over the past years. A study published in May 2021 by Oxford Sustainable Finance Programme analyzed the financing costs for coal-fired power plants and other energy technologies were compared between 2007-2010 and 2017-2020. The authors found that the loan spread for coal power plants have increased on average by 38%. This compares to a decrease of financing costs of 24% for offshore wind, 12% for onshore wind, and an increase of 7% for gas power plant. This has made financing coal power plants the most expensive of all power generation technologies.

Besides increasing financing cost for coal power plant, operation costs have also become more volatile due to the volatile prices of their fuel – coal (see Figure 5): Coal prices have fluctuated between USD40 in 2016, risen to about USD80 in 2018, dropped to USD25 in 2020 during the corona pandemic and have risen as of late to USD108 per ton.

Competition of lower priced green energy sources

Over the past 10 years, the cost of producing and buying solar panels has dropped faster than most experts predicted. This has allowed the price for producing electricity with solar panels to drop by a factor of 5 since 2010 (see Figure 6).

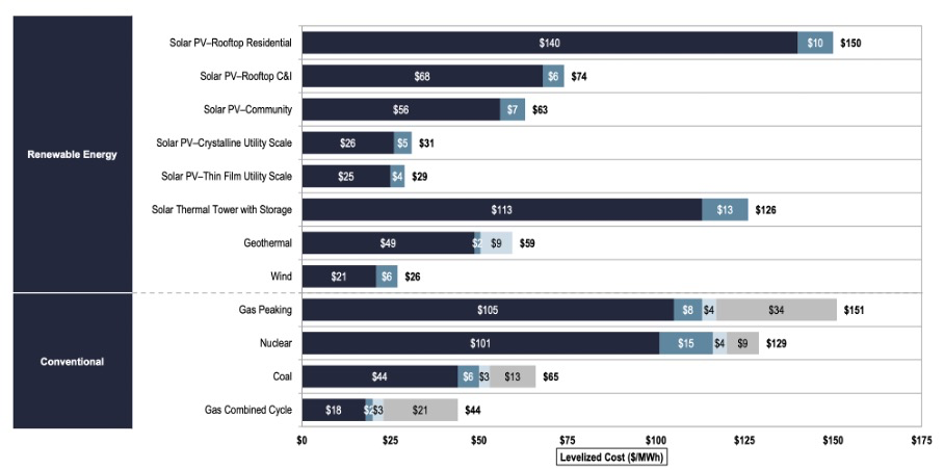

To compare the price of different electricity sources, the concept of levelized cost of energy (LCOE) has been developed that integrates different costs – from production cost, to capital cost to fuel costs and maintenance. According to Lazard, a consultancy analyzing LCOE, decreasing capital costs, improving technologies and increased competition has allowed the LCOE for solar to fall by 90% and reach about USD30 per MWh. This compares to a cost of about USD65 for producing one kWh with a new coal-fired power plant (older coal investments are likely to have higher LCOE) (see Figure 7).

The rapidly decreasing cost for solar technology, has allowed for new records for lowest solar price bids over the past year – that are even below the LCOE above:

- In April 2020, Abu Dhabi confirmed a solar bid of USD0.0135/kWh in a 1.5 GW tender

- In August 2020, Portugal confirmed about USD0.013/kWh in a 700MW solar auction

- In November 2020, India confirms a USD0.027/kWh in a 1,070 MW solar project.

Climate related financial risks

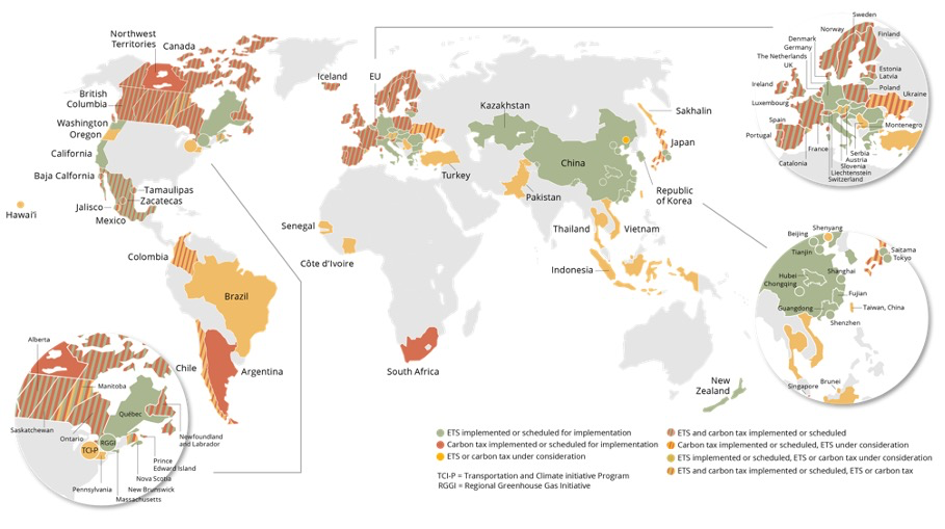

In addition to rising cost for coal and stronger competition through alternative energies, investors are also increasingly integrating climate risk into their decision-making. One of the most prominent risk is the introduction of carbon prices, which immediately affect the bottom-line of coal-fired power plants.

World Bank statistics show that in 2021, 64 carbon pricing initiatives were in operation. This compares to 58 initiatives in 2020 and 47 in 2018. These carbon pricing mechanisms often specifically target high-emitting coal-fired power plants to charge a price for carbon emissions. Relevant carbon-prices for Chinese investors in overseas coal have particularly been introduced in South-East Asia (see Figure 8).

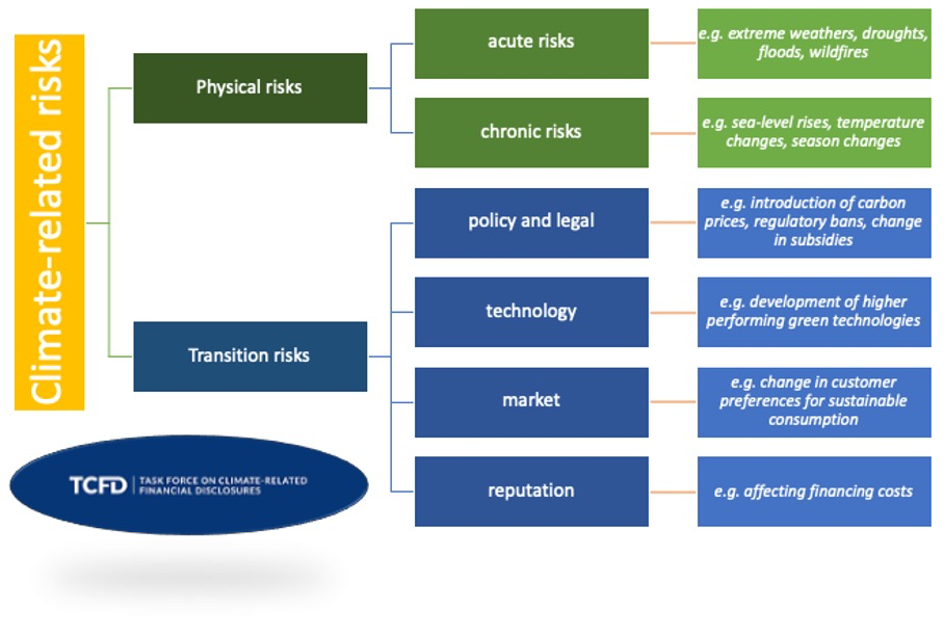

To better understand climate-related financial risks (and integrate also future carbon prices in investment decisions), investors are increasingly looking beyond the directly measurable costs of climate change. With encouragement or enforcement through regulators and central banks, such as the Bank of England as well as the People’s Bank of China frameworks, such as the Task-force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) are used to evaluate such risks.

The TCFD distinguishes two classes and 6 types of financial risks related to climate change (see Figure 9). The physical risks are determined by acute weather events (e.g., droughts, floods) and longer-term risks affected by climate change (e.g., sea-level rise, changing season rainfalls, rising temperatures). The transition risks are determined by policy and regulatory frameworks (e.g., through the introduction of carbon prices), by technological developments (e.g., lowering prices for green technologies), by market forces (e.g., changing consumer patterns preferring green consumption), and by reputational factors.

While most asset classes (including coal-related assets) are affected by physical risks (e.g., agriculture or real estate suffer from extreme weathers or sea-level rises), institutions involved in coal-fired assets are particularly exposed to transition risks.

Stranded asset risks and its consequences

As a consequence of increasing cost for coal through higher financing cost, higher fuel costs, higher cost for emissions, paired with increasing competition from lower-priced alternative energy sources, Institutions engaged in coal-related assets see themselves increasingly exposed to stranded asset risks: it simply becomes cheaper to produce electricity with alternative sources and less competitive to produce it with coal.

For relevant institutions in host countries, it is thus often cheaper to mothball existing coal-fired power plants (or those under construction) and invest in new solar and wind, rather than burning more coal and – with it – cash. The alternative is to continue to pay a higher price for electricity, which would either have to be paid for by the taxpayer in forms of subsidies or to support power purchasing agreements, or directly by the consumers.

The stranded asset risk problem is therefore not only a problem of possible new coal installations, but for existing coal plants as well.

Recommendations

In order to reduce stranded asset risks for Chinese investors in the BRI and accelerate a green BRI construction, relevant financial institutions can take number of steps:

- Continue to reduce new coal-related investments in the BRI including coal-mining: while coal-fired power plants have already come under scrutiny, other coal -related investments (e.g., mining) are potentially equally at risk. In a May 2021 study, the IEA found that no new coal mines are required if the world is serious about reducing climate emissions;

- Develop and implement phase-out plans for existing coal assets in the BRI countries: investors should look into possibilities to apply early retirement plans for existing coal plants to reduce both the high cost of producing electricity through coal and benefit from higher profit margins in green energy;

- Cooperate with international sponsors and host countries to accelerate phase-out of existing coal: evaluate net-present value of existing coal-fired power plants and consider applying for special funding (e.g., from international donors or in debt-for-climate swaps) to pay for early retirement of coal-fleets that have a higher net-present value than comparable green investments;

- Include social considerations in the phase-out plans: investors together with the operators of the existing coal fleets should develop phase out plans that are not only financially and environmentally sound, but also consider social aspects. Accordingly, the phase-out plans should include cooperation with local suppliers of training programs for existing coal-fired power plants employees training programs for other jobs, e.g., in the green energy sector;

- Be prepared for similar developments affecting other fossil-fuel investments, such as gas-related investments: while some believe gas could be used as a transition technology from a coal-based to a zero-emission energy system, evidence points to large issues of gas-fired power plants having similar or potentially worse greenhouse-gas emission effects than coal, particularly due to gas leakage;

- Share risks with other investors and partners where possible and share learnings and capacity with international community, for example by issuing green bonds or sustainability-linked bonds to support the transition and green investments;

- Improve risk-management of projects that focus on environmental and social issues: improve EIA (environmental impact assessment) requirements and environmental and social risks management systems (ESRM) to include climate considerations and social considerations for better avoidance and management of risks;

- Utilize the opportunity of green investments with much energy demand and transition finance required, which increasingly provides stable returns at lower cost.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.

Comments are closed.