On March 5 during the “Two Sessions”, China introduced its 14th five-year plan for 2021 to 2025, as well as the Government Work Plan. In it, China vows to focus on “green development”, to uphold the “30-60” promise of Xi Jinping for China to try to peak carbon emissions before 2030 and be carbon neutral by 2060 and to be a role model for climate governance in the world. Accordingly, it announced to “expedite the transition of China’s growth model to one of green development”, improve carbon emission intensity (the emissions produced by one unit of GDP) by 18% in five years, its energy intensity (the amount of energy used for one unit of GDP) by 13.5%, and to increase the share of renewable energies to 20%, from today’s 15%.

But, analyzing these announcements reveals that current ambition levels should be seen as a baseline, as current targets risk undermining global climate goals: If China achieves its emission intensity reduction target of minus 18%, China’s CO2 emission could increase by up to 10% by 2025 compared to 2020, if annual GDP growth reaches 6% over the next years (China hopes to reach more than 6% in 2021 and Deutsche Bank predicts a 10% GDP growth for China in 2021). To put that into comparison: With Chinese current emissions of well above 10 billion tons per year, another 10% of CO2 emissions would be equal to the current emissions of the UK, South Africa, and Egypt – combined. If these additional annual emissions would come from one single country, this country would be the world’s fourth largest emitter (after China, US and Russia).

While China has featured its strong climate and green ambitions ever more prominently over the past months, the China’s 14th five-year plan did not accelerate China’s climate ambitions compared to the 13th five-year plan (2016-2020). This stands in contrast to many developed and developing countries that have accelerated their climate ambitions over the past years: not only the EU and the US, but also many emerging markets, such as Pakistan, Vietnam, Bangladesh, have put in place measures to accelerate emission reduction, e.g. announcing a ban on coal investments, or by announcing an absolute emission reduction goal in their NDCs or at least a cap of maximum emissions and by focusing their recovery plans on renewable energies.

In consequence, more specific plans should be drawn up to use the five-year plan as a baseline: higher immediate reduction of intensity are possible, e.g. by accelerating the use of green finance for renewable energy investments, energy efficiency investments and phasing out of polluting investments. After all, every increase in emissions over the next years makes China’s ambition to be carbon-neutral by 2060 ever more difficult.

China and global climate

Since 1990, China grew its GDP by almost 40 times and its GDP per capita by almost 32 times, according to World Bank data. With GDP growth, emissions grew as well: from 1990 to 2020, China increased its emissions from 2.4 billion tonnes to over 10 billion tonnes, making it the country with the largest absolute greenhouse emissions and also surpassing the EU in regard to per capita emissions in 2016, despite a GDP per capita of about 40% of the EU.

With China’s climate footprint mattering more than almost any other country, its signature of the Paris agreement in 2015 was paramount. In it, China agreed to limit global warming to less than 2°C by 2050 and therefore, effectively, agreeing to a climate-neutral economy by 2050.

In September 2020, Xi Jinping “specified” China’s climate commitments and vowed to strengthen efforts to peak China’s carbon emissions before 2030 and be carbon neutral by 2060. This announcement, despite being a de-facto revision of the Paris Agreement, received much praise in China and the international community.

One hope was that China would strengthen its climate and green ambitions, particularly through policies expressed in its five-year plan, which sets the strategic economic and social development trajectory of China. Such a strengthening of climate ambitions could have included an absolute cap of greenhouse gas emissions, which so far is unspecified in China, or a clear trajectory of emission reductions. Yet, the five-year plan published on March 5th, 2021 offers not much news compared to its predecessor published in 2016: Most importantly, China vows to reduce its emission intensity by 18%, energy intensity by 13.5% and to increase the share of renewable energies to 20%, from today’s 15% (see above).

While this may sound ambitious at first sight, the impacts on climate when using the five-year plan’s goals verbatim will lead to up to 15% higher emissions for China, and thus up to about 4% more global emissions.

Calculating the impacts of the five-year-plan targets on climate and energy

To calculate China’s future emissions, energy needs and energy shares, this article uses 2020 as a baseline year. All values (e.g. GDP, energy efficiency, energy use, emissions) in the baseline year are set at 100. Accordingly, based on the growth plans and the targets, values can be calculated, e.g.

| 2020 | 2021 | |

| GDP | 100 | 106 (6% more than in 2020) |

| Emission intensity | 100 | 96,4 (3,6% less than in 2020 with the goal to decrease by 18% in five years) |

| Emissions (=emission intensity*GDP./.100) | 100 | 102,18 |

| Energy intensity | 100 | 97,3 (2,7% less than in 2020 with the goal to decrease 13.5% in five years) |

| Energy use (=energy intensity * GDP ./.100) | 100 | 103,14 |

| Renewable energy share | 15% | 16% (5% more renewable energy share by 2025) |

| Renewable energy use (=energy use*renewable energy share) | 15 | 16,5 |

| Non-renewable energy share | 85% | 84% |

| Non-renewable energy use (=energy use * non-renewable energy share) | 85 | 86,64 |

However, as China has not officially set a GDP growth target for the 2021-2025 time frame, while it hoped to achieve well above 6% GDP growth in 2021, this articles takes two different scenarios based on realistic growth goals over the next 5 to 10 years to calculate emissions and energy needs: 5% and 6% GDP growth per year. Furthermore, to compare China’s historic CO2 emissions, this article uses World Bank data. To calculate possible peaks of emissions and energy needs, this article assumes a continuation of China’s economic development based on the targets of 13th and 14th five-year plan until 2030 and beyond. Therefore, emission intensity reduction targets will remain at 18% over the next 10 years, energy efficiency reduction targets will remain at 13.5% and GDP growth will remain at 5% and 6%.

Climate emissions in China’s five-year plan 2021 to 2025

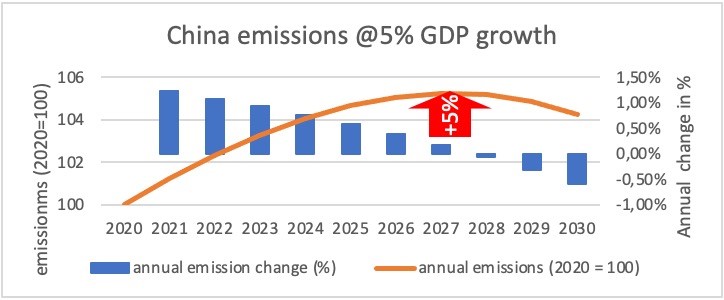

In the 5% growth scenario, Chinese CO2 emissions would peak around the year 2027, 3 years ahead of the current ambitions to peak before 2030. This scenario would lead to 5% more CO2 emissions compared to today, and 449% more emissions compared to the 1990 baseline. These additional emissions would be equal to the emissions of South Africa in 2019 (see Figure 1).

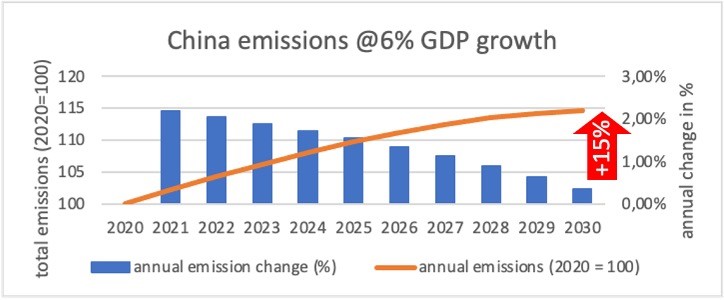

In the 6% growth scenario, Chinese CO2 emissions would peak in 2031, 1 year later than the current ambitions of peaking before 2030 (see Figure 2). China would add up to 15% of emissions compared to 2020, which equals to 489% more emissions compared to the 1990 baseline. These additional emissions would be similar to the combined emissions of Poland, UK, South Africa and Brazil in 2019 (see Table 1).

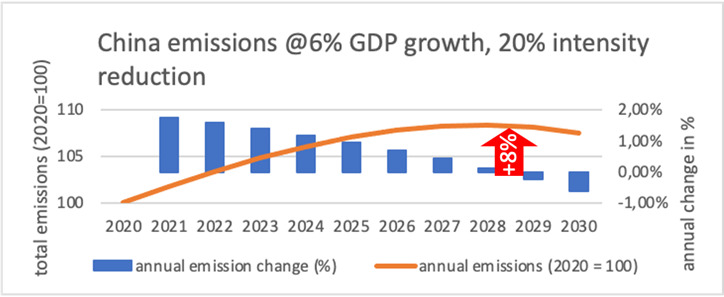

Assuming China can accelerate the use of green finance and keep up previous improvement of its emission intensity of 20% in 5 years, peaking of China’s emissions would happen in 2028 – two years ahead of the 2030 target. In this scenario, China would emit about 8% more of carbon emissions compared to 2020, or 462% more emissions compared to the 1990 baseline.

| Scenario | Emission intensity reduction in 5 years | Peak year | Peak emissions delta to 2020 | Peak emission delta to 1990 | Additional annual emissions in peak year (tons) compared to 2020 | Additional emissions comparable to |

| 5% GDP growth per year | 18% | 2027 | +5,25% | +449% | ~5 million | South Africa |

| 6% GDP growth per year | 18% | 2031 | +14,65% | +489% | ~15 million | Poland, UK, South Africa, Brazil (combined) |

| 6% GDP growth per year | 20% | 2028 | +8,38% | +462% | ~8 million | Poland, South Africa (combined) |

China’s renewable and fossil fuel electricity supply

Currently, China produces about 7,623 TWh of electricity, with 3.4% coming from solar, 6% coming from wind, and 62% coming from coal. Due to the intermittence in wind and solar power, generating capacity of both of these two green energy sources is much higher than their share of the electricity – taking more than 10% each of total generating capacity. In other words, currently, the share of green energy installations is about double their share of the electricity mix. In 2020, China added about 70 GW of wind and 50 GW of solar capacity, compared to about 191 GW of new coal to the electricity grid.

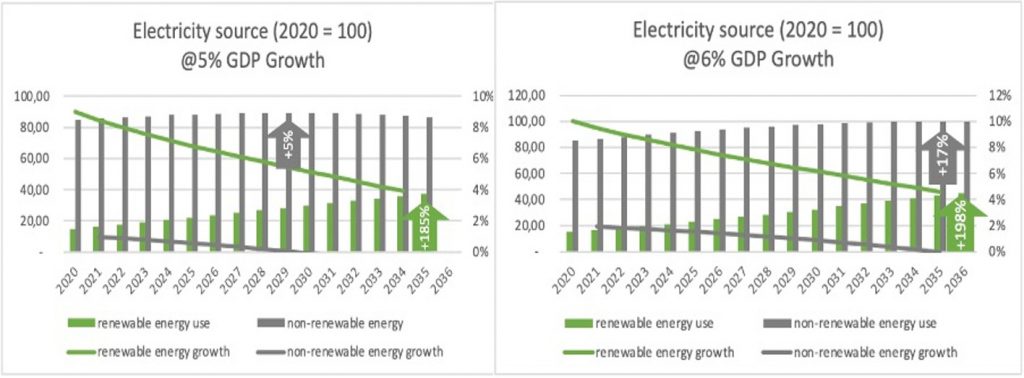

Calculating electricity needs over the next years according to China’s energy intensity targets in the five-year-plan (-13.5% every five years) and renewable energy targets (+1% share per year), China would require further electricity generation capacity of 20% and 30% by 2030 for the 5% and 6% growth scenarios. Depending on the growth scenario, China would continue to increase its electricity needs until 2037 and 2040 respectively.

To achieve these electricity capacity additions and assuming an increasing share of renewable electricity per year by 1%, China would also need to increase non-renewable electricity until 2029 by 5% and 2035 by 17% respectively (see Figure 3). In the 6% growth scenario, China would meet a larger share of the new electricity needs through non-renewable than renewable energies until 2022.

Yet, what becomes clear looking at Figure 3, is that these trajectories do not fully encompass the potential growth scenario of renewable energies: The applied calculations assume an annual growth of the share of renewables by 1% as envisaged by the current five-year plan, but does not factor in a possible acceleration to install renewable energies. Accordingly, by accelerating the use of green investments, such as renewable energies and relevant policies to support this, a faster growth of renewable energies should be achievable.

Table 2 provides an overview of the impacts of the 14th FYP on the energy needs.

| GDP Growth Scenario | Peak electricity | Peak non-renewable | Peak additional non-renewable | Additional capacity renewable by 2030 |

| 5% | 2037 | 2029 | +5% | +89% |

| 6% | 2040 | 2035 | +17% | +117% |

China’s climate leadership in the BRI

China wants to “play its part in the global response to climate change”, according to Li Keqiang’s government report at the Two Sessions, it wants to “make a contribution to lead in global climate governance”, according to the State Council’s Guiding Opinions on Green and Low Carbon Circular Development and “lead the way by example” in developing a greener future.

A particular focus of China’s leadership abroad is its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China is investing billions of dollars into BRI countries to improve infrastructure, particularly energy and transport and providing capacity building to “build a green Belt and Road Initiative”.1 Accordingly, China is investing an increasing share of its energy investments in the BRI into renewable energies.2

To understand China’s leadership potential in the field of climate governance and green economic development compared to other BRI countries, it is relevant to understand the performance of the BRI countries including China on the indicators that China focuses on in its domestic climate ambitions: emission intensity and energy intensity. Accordingly, this analysis provides a comparison of BRI countries’ energy efficiency and emission intensity.

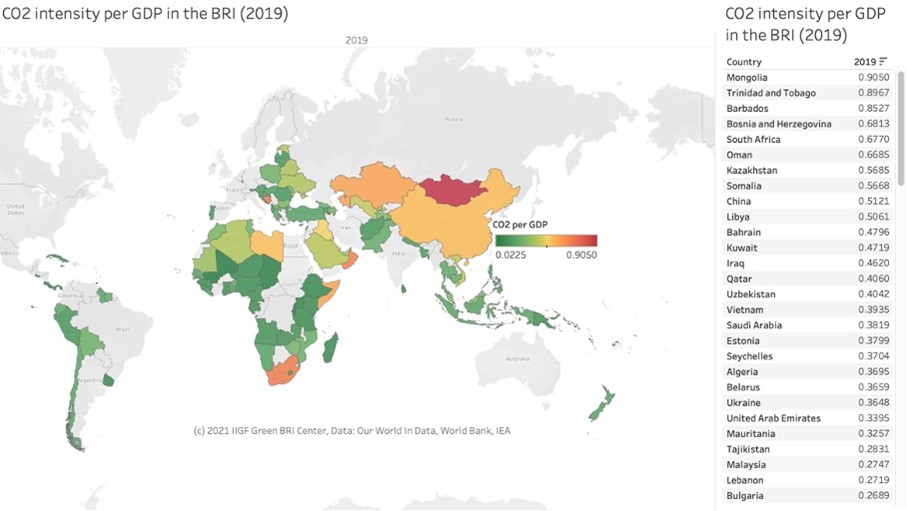

Emission intensity in the Belt and Road Initiative

Data on emission intensity from BRI countries (see Figure 4) show that many BRI countries have high emission intensities. Among the BRI countries with the highest emissions intensities are Mongolia, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados and South Africa, with China being the 9th most emission intense of the 140 BRI countries. This stands in contrast to BRI countries, particularly in Eastern Europe BRI countries and African BRI countries, as well as all Latin American BRI countries that have relatively lower emission intensities.

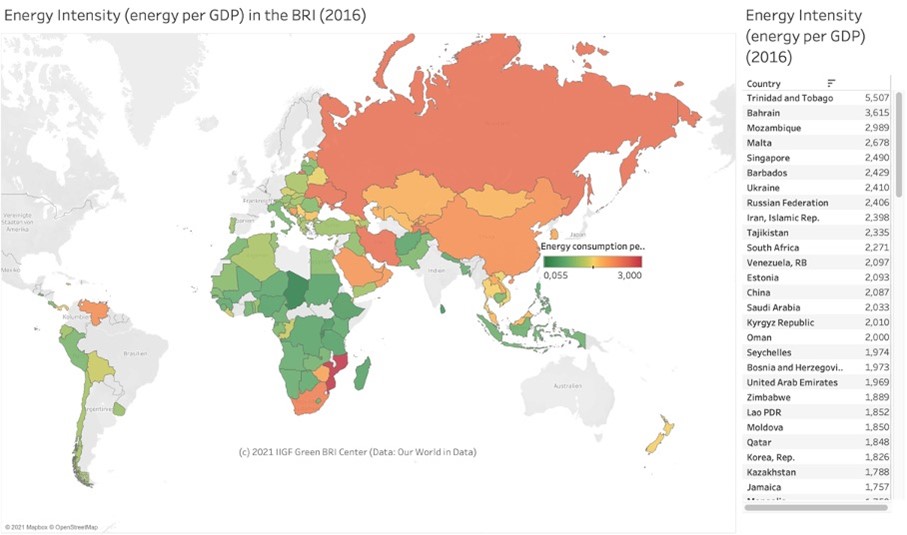

Energy intensity in the BRI

Looking at data on energy intensity in the BRI (see Figure 5), one can see that many Asian BRI countries, such as Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, as well as some African countries, like South Africa and Mozambique, require relatively more energy to generate their GDP. China’s is the 14th most energy intense of the BRI countries. This stands in contrast to most African and Eastern European BRI countries that have a higher GDP output per unit of energy and thus use less energy to generate economic growth.

BRI country activities for climate change

A number of BRI countries have announced to phase out coal investments or have cancelled coal-fired power plants to focus on renewable energy investments and reduce carbon emissions. Among these countries are

- Pakistan announced a coal exit in December 2020

- Bangladesh announced to reconsider its coal ambitions in the middle of 2020, with a further cancellation of Chinese-funded coal-fired plants in February 2021

- Vietnam has announced to build back green after COVID19 (but agreed with Japan to fund another coal fired power plant (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-12-30/japan-risks-green-backlash-with-vietnam-coal-power-plant-loan))

- Egypt in March 2020 postponed a USD 4.4 billion 6 GW coal fired power plant

- Kenya in July 2019 halted the construction of the Lamu coal fired power plant

In summary, China’s current economic growth model seems more energy intense and emission intense than most BRI countries.

Recommendations for increased green investment and finance for China’s climate leadership at home, in the BRI and for the world

In order for China to fulfill both its domestic and global pledge to focus on green development and adhere to the Paris agreement, it seems that China’s 14th five-year-plan provides ideally a baseline, rather than China’s maximum climate ambitions. Based on its historical achievements, China’s has the ability to achieve higher emission intensity reductions: between 2005 and 2010, China reduced its emission intensity by 45%, from 2010 to 2015 by 37% and from 2015 to 2020 by 20%, according to own calculations based on World Bank data.

Thus, with relevant policy and financial support, a much faster transition should be possible. One important aspect to accelerate China’s climate ambitions and thus to protect the global climate is to increase the use of green finance to accelerate more investments into green assets, while accelerating phase-out non-green investments. China has championed regulation on green finance, particularly since 2016, and relevant regulators (e.g. PBOC) are currently revising the green bond catalogue and disclosure frameworks.

Besides disclosure and green bond catalogues, policy can play an important role both domestically and in the BRI along following dimensions to increase demand for green finance and investment:

- Energy efficiency: By setting conditions that increase need for energy efficiency, investments (e.g. buildings, manufacturing, waste), energy use would decrease and thus energy efficiency would increase. Two important policies are relevant to propel green finance and investment:

- Energy prices: China’s energy prices are basically mandated by the government and held relatively low compared to international standards. By increasing energy prices, e.g. through some level of market reform and integration of carbon prices, energy efficient companies would become more competitive and would receive more investments, while energy-inefficient companies would have to upgrade.

- Garbage disposal and emission prices: By introducing higher prices for garbage disposal and other emissions (e.g. water), companies would invest in reducing pollution and garbage, and thus produce less waste. Ideally, this would lead to the production of higher quality products requiring less renewal and thus create more value, while production processes should become more efficient to produce less faulty products.

- Carbon price: By increasing the price for carbon, investments will flow into more carbon-neutral assets. An important tool is at China’s disposal: the national carbon market (ETS), which was launched in 2016 and in 2020. However, currently the national carbon market is not operating effectively to curb carbon emissions, as it only includes highly polluting energy industries (e.g. thermal power) and as is not operating on a cap and trade, but on an emission intensity target. This set-up potentially provides perverse incentives for “less polluting” coal-fired power plants to produce more electricity (and thus more emissions), while earning money by selling carbon credits. This would, potentially, crowd out renewable energies.

The ETS should accordingly be designed with a clear cap for emissions, and include more sectors, such as manufacturing and allow for carbon-offsets from the renewable energy sector. Furthermore, the electricity market should be able to reflect the prices of the carbon prices in electricity prices, compared to the current mandated electricity price.

This would allow further investments, particularly in renewable energies. - Disincentivizing brown energy: China should accelerate investments in green energy, most importantly by phasing out coal investments and ideally fossil-fuel related investments. This would set relevant incentives for all investors (not only green) into accelerating investments into renewable energies, as fossil fuel investments are just not possible anymore.

- Global leadership and cooperation: China is among the most important players in the fight against climate change. It can lead by example and set important milestones in global climate governance. At this time, however, China is falling behind and is at risk of losing credibility due to much talk on green, but lack of clear ambitions, targets and results. To take back momentum, China could

- Announce an immediate stop of new overseas coal-fired power investments both on commercial and on soft-loan terms, while at the same time increase funding for overseas green energy in accordance with the Green Development Guidance published in December 2020;

- Further regulate overseas investments in accordance with climate and biodiversity

- Increase its domestic ambition to set an emission cap to 2025 to 440% over the 1990 baseline.

- Increase cooperation and opening up of green finance and investment opportunities at home and abroad to accelerate funding and investments into green economy.

- Invest in the climate-biodiversity nexus by providing frameworks and incentives for the construction of nature-based solutions for climate resilience (e.g. green sponge cities) and climate mitigation (e.g. carbon sinks).

- Accelerate investments in green technologies, particularly plant-based foods, energy efficient buildings, energy storage both domestically and through international cooperation

Overall, the opportunity for China to lead in climate change by example through the application of policy, domestic and international green technologies, domestic and international green finance and a large market are on the horizon – all while accelerating China’s transition to a green and high-quality economy. Yet, to achieve this goal China would need to develop more relevant ambitions and walk the talk for a de-facto implementation of the goals.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.

Comments are closed.