China announced coal phase-out in Bangladesh

In February 2021, China’s embassy in Bangladesh sent a letter to the local Ministry of Finance stating that “the Chinese side shall no longer consider projects with high pollution and high energy consumption, such as coal mining [and] coal-fired power stations”.

Why did China suddenly announce a coal investment phase-out in Bangladesh?

In 2016, China and Bangladesh signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) for 27 projects valued at $24 billion, including a variety of projects in infrastructure and energy. In February 2021, Dhaka requested to replace 5 projects in the MoUs worth $3.6 billion in Chinese loans:

- Dhaka-Sylhet four lane highway project ($2,110 million).

- Extension of Barapukuria coal mine’s existing underground operations ($256.41 million).

- Bangladesh Power Development Board’s distribution zones ($521.56 million).

- Gazaria 350-megawatt coal-fired thermal power plant ($433.00 million).

- Balancing, modernisation, rehabilitation and expansion of public jute mills of Bangladesh Jute Mills Corporation ($280 million).

The Gazaria coal-fired power plant was supposed to be implemented by Rural Power Company Limited (RPCL). However, RPCL said that the company had to drop the idea to set up a coal-fired power plant in Gazaria in the wake of massive protest from local people against the coal plant in their locality. This eventually contributed to the decision by Bangladesh’s government to exclude the Gazaria power plant from the MoUs signed with China. The Dhaka-Sylhet four-lane project was removed from the list over corruption issues and a multilateral lender has agreed to provide the fund. As for the remaining three projects, since they are not on the Bangladesh government’s priority list, it is therefore not keen to implement them using Chinese fund.

In response to Bangladesh’s exclusion list of 5 projects, China’s embassy announced the coal investment phase-out in Bangladesh, and suggested that the Bangladesh side select new projects, which should be smaller in scale and meet standard requirements, such as having an associated feasibility study and environmental protection plans.

The decision by Bangladesh’s government to replace these 5 projects likely reflects its current domestic power system situation, its energy development strategy shift and its recognition to stipulate greener development compared to coal-based energy. On the other hand, China’s response shows support for Bangladesh government’s willingness to move away from domestic coal-fired power plants investments – and possibly more broadly in the whole Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Reasons behind Bangladesh’s decision: power overcapacity and cost issues

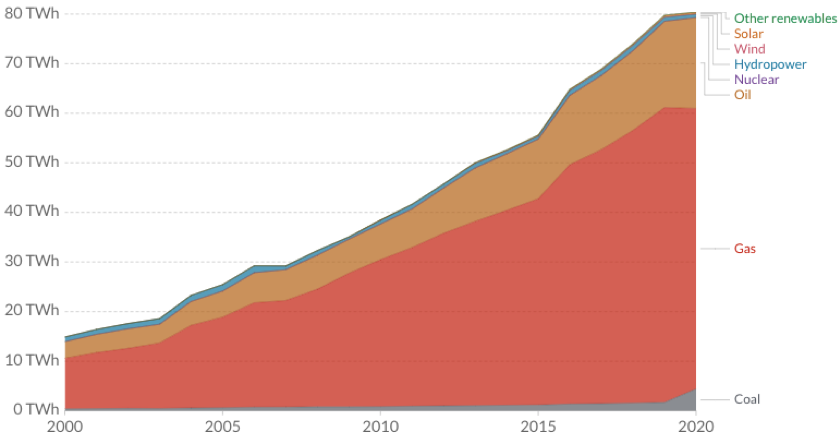

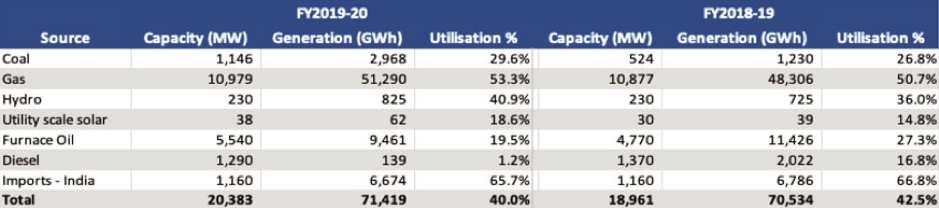

In 2020, gas accounted for the majority of Bangladesh’s electricity production (around 70%), while coal accounted for about 5%. The shares of renewables such as wind, hydropower and solar PV in the electricity mix were quite small, fluctuating from around 6% in 2000 to 2% in 2010, and then to 1.4% in 2020. The current energy mix is far away from achieving Bangladesh government’s target of meeting 10% of power demand from renewable energy resources by 2020.

Electricity generation by source, Bangladesh 2000-2020

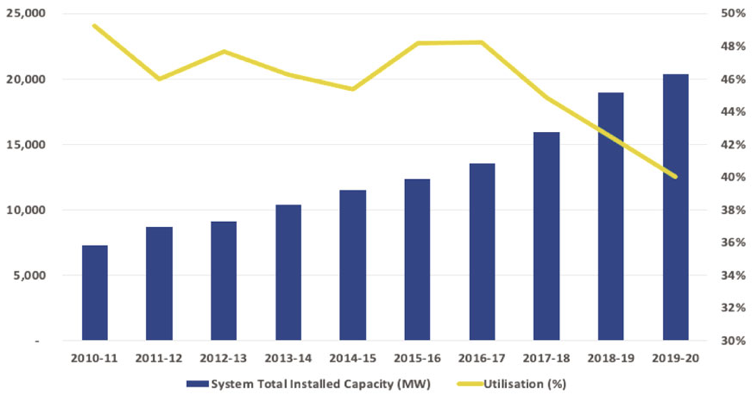

As shown in the two graphs below, Bangladesh’s total installed power capacity has been increasing since 2010, while the actual power generation growth rate could not keep up with the same pace (around 1% from FY2018-19 to FY2019-20). This led to low capacity utilization rate. In other words, overcapacity issue arose. Since 2017, the capacity utilization rate continued to decline, reaching its lowest level of 40% in 2020.

Bangladesh power capacity, generation and utilization change: 2018-2020

Bangladesh power capacity and capacity utilization

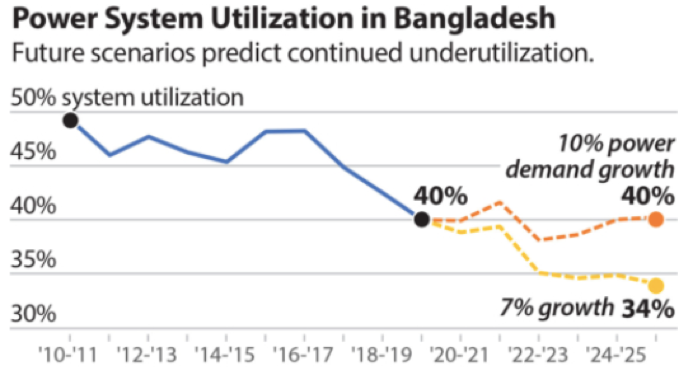

Accordingly, the think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) pointed out that Bangladesh’s power system is characterized by massive overcapacities with risks of further deterioration. Simon Nicholas, an energy finance analyst with IEEFA, said that planned capacity additions over the next five years would likely see capacity utilization decline further. If power demand growth could reach 10%, then it is possible to keep capacity utilization around 40% in the next five years. However, if power demand growth only reaches 7%, then capacity utilization could further decline to around 34%.

Worsening overcapacity would have significant financial burden for the Bangladesh Power Development Board (BPDB): BPDB already pays costly subsidies to operators of underutilized power plants in the form of “capacity payments”. This situation was made worse since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, as power demand declined. This situation risks leading to a further rise in capacity payments, unless steps are taken to revise plans for new capacity. With a coal power utilization rate of just 43%, from 2018-19 the Bangladesh government reportedly burnt US$1.1 billion in payments to power plant operators.

Therefore, now more than ever, large fleets of big coal plants are increasingly less appropriate to meet lower-than-expected electricity demand in Bangladesh.

Current situation of Bangladesh’s coal-fired plants

Bangladesh government is well aware of the overcapacity risk and financial burden of coal-fired plants. In July 2020, Nasrul Hamid, Bangladesh’s Minister of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources, said the country was planning to “review” all but three of 29 planned coal plants. Of the 29 projects, work on 18 projects is underway. Later in August, the Ministry of Power, Energy and Mineral Resources of Bangladesh sent a letter to the Prime Minister’s Office to propose that 5 of these 18 projects be completed as coal-fired plants, while the remaining 13 coal-fired power plants be converted into liquefied natural gas (LNG)-based plants. These 13 projects have already acquired land, but made little progress, e.g., as they could not secure financing. As for the rest 11 projects out of 29, the government might gradually cancel them.

The 5 plants that were suggested to continue as planned are: Maitree 1,320MW Super Thermal Power Project; Matarbari 1,200MW power plant; Payra 1,320MW Thermal Power Plant Project, and two other power plants set up in Chittagong and Barishal by Bangladeshi companies S Alam Group and Barishal Electric Power Company Ltd.

Of the 5 plants, Payra is being developed by Bangladesh China Power Company (BCPCL), which is a 50:50 joint venture between China National Machinery Import and Export (CMC) and Bangladesh’s state-owned North-West Power Generation Company (NWPGCL). The remaining 4 plants involve financing from Japan, India, and Bangladesh itself.

Reflection on China’s decision to phase out coal in Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s government only asked to exclude 5 projects from MoUs with China rather than excluding all Chinese financed projects. Accordingly, it is currently unclear what happens with the other plants. If China would exit of all coal projects investments in Bangladesh, it could be a wise decision. Given Bangladesh government’s growing disfavor of coal-fired power plants and ongoing reviews of them, China’s investors would be able to avoid potential investment losses by quitting new coal financing altogether in Bangladesh.

An exit of coal financing would also give more space for China to focus on greener and more profitable investment opportunities, such as renewable energies, in Bangladesh: In 2020, Bangladesh government invited China to accelerate its renewable energy ambitions because private sector investors were not driving forward solar deployment fast enough. Bangladesh’s North-West Power Generation Company Limited and Chinese engineering contractor the National Machinery Import and Export Corporation formed a joint venture (JV) called Bangladesh-China Power Company (Pvt) Ltd Renewables entity. It plans to build 450 MW of new solar capacity and a 50 MW wind farm. As part of the Public Private Partnership (PPP), Bangladesh’s government would supply land for clean energy generation while China would invest an estimated $500 million in developing the planned solar and wind facilities, via the new joint venture.

This joint venture sets a good example for China’s BRI energy investment choices. By turning investment away from coal to renewable energy, China could not only help Bangladesh greening its energy mix, but also contribute to global climate goal.

From Bangladesh to China’s global coal investments

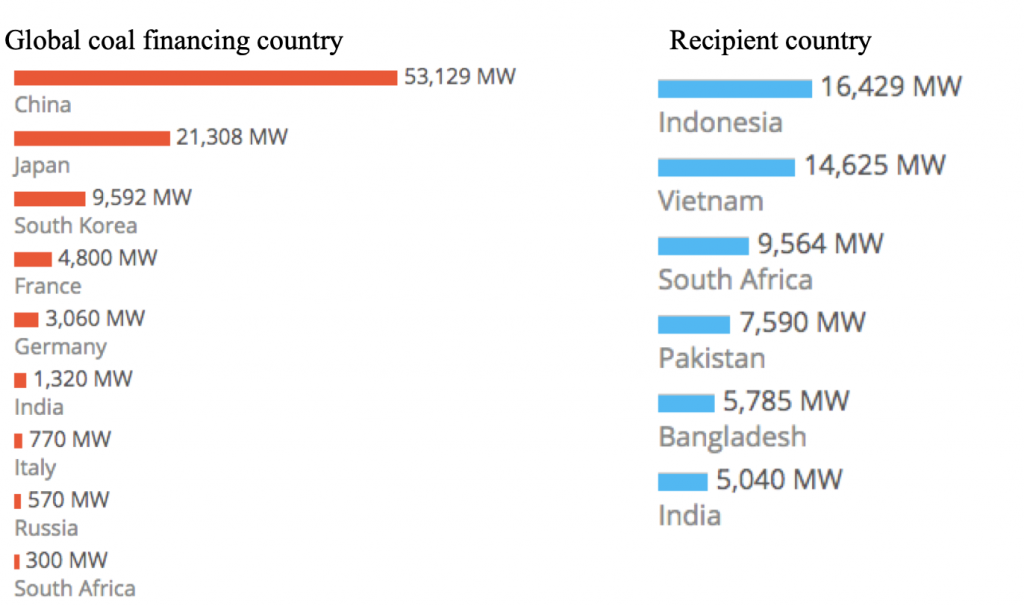

Outside of Bangladesh, coal investments have come under scrutiny around the world due to their negative climate impacts and due to the stranded asset risks associated with them. To understand global exposure to coal, it is worth looking at data from the Global Coal Finance Tracker – which monitors government-affiliated financial institutions’ direct support of overseas coal power projects. According to these data, more than 70% of all coal plants built today are reliant on Chinese funding, with Japan and South Korea following in second and third place. The biggest coal financing recipient countries are Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) countries, such as Indonesia, Vietnam and South Africa.

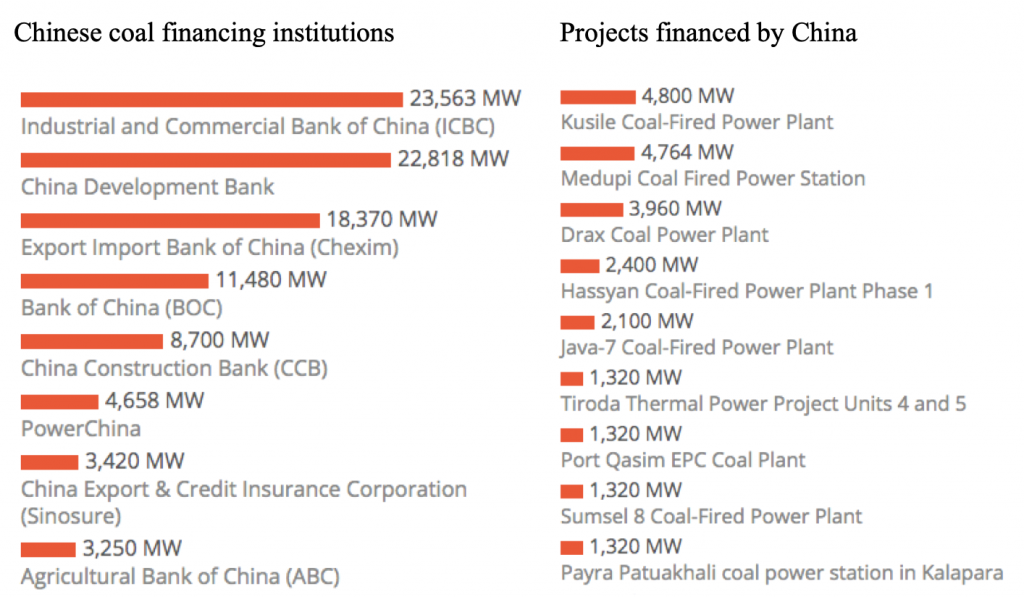

Looking closer at Chinese funding of current 53129 MW coal-fired plants, the graphs below list the top financing institutions and the projects already financed by China. ICBC, CDB, Chexim and BOC are the top lenders for international coal power constructions such as the 4800 MW Kusile Coal-Fired Power Plant in South Africa and the 1320 MW Payra Patuakhali coal power station in Bangladesh.

Global efforts to restrict or phase out coal investments

Many international parties including financial institutions already restrict or quit global coal financing.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) have both signaled they would no longer support coal. In addition, the region’s biggest coal financiers Japan and South Korea have started use regulation to curtail their support for overseas coal projects under mounting international pressure. Also China has signaled broader interest in reducing overseas coal-financing in the BRI: China’s Central Bank announced to strictly control coal investments in the BRI in April 2021, (People’s Bank of China (PBOC) 2021), while the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), the Banking Regulator CBIRC and the NDRC backed the Green Development Guidance BRI Projects that put coal on restricted “red” project list in the Traffic Light System for the BRI (Nedopil et al. 2020).

Also, private financial institutions are announcing their exit of coal: 26 of 35 major global banks being analysed in the Banking on Climate Change 2020 report now have policies restricting coal finance and more than a dozen also restrict finance to some oil and gas.

Currently, however, Chinese banks investing in the BRI, including Bank of China (BOC), Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) had few to no policy provisions regarding their involvement with fossil fuels.

How could China better support BRI countries to accelerate coal investments phase-out?

In order for BRI countries to accelerate domestic coal investments phase-out, both China and BRI host countries are responsible for certain actions.

Host countries are perfectly capable of making their own decisions to end domestic coal investments in order to solve overcapacity issues and transition to renewables. Here are two other examples besides Bangladesh.

In December 2020, Pakistan’s Prime Minister announced that his government would not approve any more coal power plants and pivot to renewables. Chinese companies had been financing or building most of Pakistan’s coal plants through the China-Pakistan economic corridor (CPEC). This announcement points a good direction for further ending coal-fired plants in other BRI countries given the strategic importance of CPEC in BRI.

Also, Egypt has postponed the construction of the Hamrawein coal-fired power plant in March 2020, as Egypt already found it already had sufficient power capacity and as it wanted to pivot away from coal and towards renewable energy.

Therefore, BRI host countries should:

- Apply the Green Development Guidance for BRI projects and request investments in energy systems considered “green” in the Traffic Light System (that is solar and wind), while restricting “red” projects, such as fossil fuels.

- Design and implement policies that favor and attract renewable energy investments, e.g., through subsidies, feed-in-tariffs.

- Develop domestic environmental policies that govern coal projects and phase out fossil fuel subsidies for electricity generation.

- Support investments in relevant infrastructure, such as smart grids, that allow for balancing supply and demand of electricity.

Relevant Chinese government stakeholders could support BRI coal-phase out:

- Put in place policies to limit or ban finance to build new coal-fired power plants in BRI countries, for example to be announced by highest levels of Chinese government before the Climate COP in Glasgow in November 2021.

- Support application of traffic light system that gives faster approvals and preferential financing for green projects, and disfavors projects on the “red” list.

- Apply international standards, such as IFC performance standards, to energy projects when host countries lack relevant governing law or policies to ensure environmental compliance.

- Encourage BRI countries to develop more renewable energy projects by providing relevant capacity building support in planning and implementation.

Chinese financial institutions could:

- Strictly implement Chinese government’s guidances, such as the Green Development Guidance with the Traffic Light System to limit or stop fossil fuel financing due to the stranded asset risks.

- Cooperate with international financial institutions in financing more green energy projects and share relevant environmental risk management capacity.

- Evaluate host countries’ future power demand to avoid overcapacity risks and energy strategy before deciding to invest.

- Give favorable lending terms for host countries on renewable projects.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative has the potential to become the largest means for the diffusion of cleaner energy technologies throughout the developing world. The BRI could not only help unlock markets for clean energy technologies for China but also meet the pressing energy needs of developing countries in a manner that is consistent with the overarching goals of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. It will only succeed, however, if BRI countries exercise more agency in attracting relevant green investments on the one hand, and if relevant investors, including Chinese investors and relevant policies support this green BRI transition.

Jingying Han

Jingying HAN was a consultant at the Green BRI Center at IIGF. She holds a master’s degree in Economics and Business (Sustainability) from SciencesPo Paris. She has worked as an intern in China’s Merchants Bank in Luxembourg as a financial analyst, EDF in Paris as research analyst on Chinese economy and Sino-European relations, CMA CGM in Marseille as sustainable supply chain transformation assistant. She is interested in climate change, carbon market and sustainable development.

Dr. Christoph NEDOPIL WANG is the Founding Director of the Green Finance & Development Center and a Visiting Professor at the Fanhai International School of Finance (FISF) at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. He is also the Director of the Griffith Asia Institute and a Professor at Griffith University.

Christoph is a member of the Belt and Road Initiative Green Coalition (BRIGC) of the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment. He has contributed to policies and provided research/consulting amongst others for the China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development (CCICED), the Ministry of Commerce, various private and multilateral finance institutions (e.g. ADB, IFC, as well as multilateral institutions (e.g. UNDP, UNESCAP) and international governments.

Christoph holds a master of engineering from the Technical University Berlin, a master of public administration from Harvard Kennedy School, as well as a PhD in Economics. He has extensive experience in finance, sustainability, innovation, and infrastructure, having worked for the International Finance Corporation (IFC) for almost 10 years and being a Director for the Sino-German Sustainable Transport Project with the German Cooperation Agency GIZ in Beijing.

He has authored books, articles and reports, including UNDP's SDG Finance Taxonomy, IFC's “Navigating through Crises” and “Corporate Governance - Handbook for Board Directors”, and multiple academic papers on capital flows, sustainability and international development.